American democracy is endangered in the most unlikely of places: Ukraine.

Events swirling around the Russian invasion of Ukraine have implications for our own freedom. I have no interest in conjuring the apocalyptic visions of rapture believers, but I do reference the Old Testament book of Danielâs graphic depiction of âbeast kingsâ who would rule our lives in fear and violence.

These beasts have real-life representatives, among them President Putin of Russia. He and his fellow âbeast kingsâ are terrifying because they know they are in a life-and-death struggle while the rest of us attempt to appease them. My concern is that we have created an environment that makes the proliferation of âbeast kingsâ more likely.

There are already cracks in the attempt to reign in Putin. Some nations have refused to condemn Putinâs invasion. Others have refused to give Ukraine aid. Then there are the voices demanding âAmerica first.â All of this endangers democracy. And now a potential problem with President Recep T. ErdoÄan of Turkey.

âI write in rebuttal of âAmerica firstâ and in defiance of right-wing populism around the world in our own politics.â

I write in rebuttal of âAmerica firstâ and in defiance of right-wing populism around the world in our own politics.

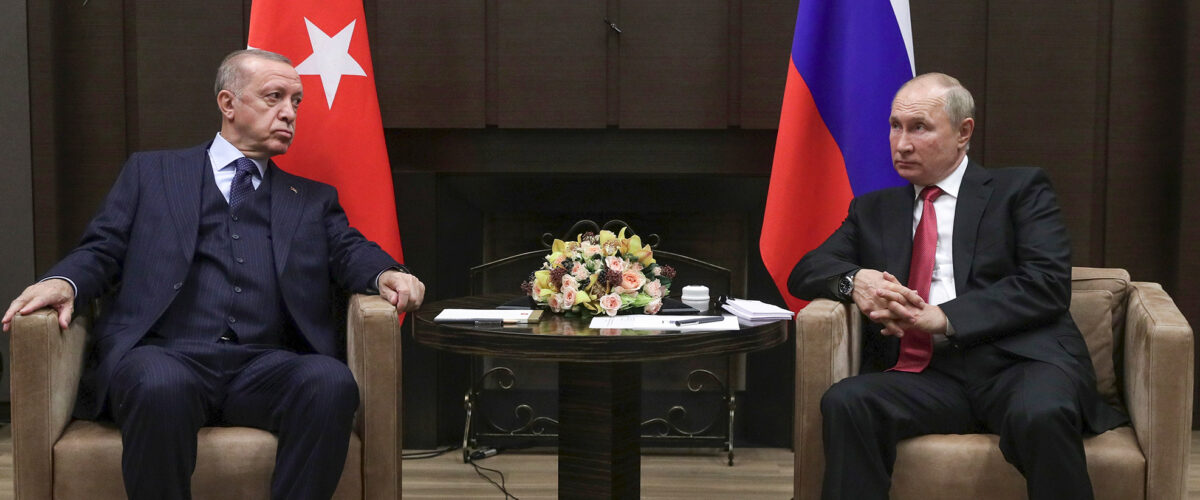

Similarities between ErdoÄan and Putin

ErdoÄan has announced he will vote against accepting Finland and Sweden into NATO membership. If you wonder why, look no further than ErdoÄanâs similarities with Putin, his support for Putin. The answer is clear.

These two leaders combine right-wing populism and authoritarianism, what some scholars are now calling âpopulist authoritarianism.â If you take one more step and then ask why Americans should care about ErdoÄan, Putin and Ukraine, then you are pursuing a necessary line of questioning that impacts our own democracy. ErdoÄan and Putin disguise authoritarianism and dictatorship while claiming to be democratically elected leaders.

Populisms of both left-wing and right-wing varieties have been proliferating around the globe with alarming speed. Initially coming to power as outsiders, these figures managed to gain official political and institutional power while never losing their status as populists. The growth of right-wing nationalist populism in nations of the North Atlantic sounds the alarm about the state of democracy in the world.

âSowing fear and suspicionâ

Once the shining star of government, democracy now loses ground to a new brand of populism. The rise of âhard-right populism is cultivated through the sowing of fear and suspicion,â according to rhetorical scholars Betul Eksi1 and Elizabeth A. Wood. Politicians have exploited feelings of disaffection among those who believe globalization has left them behind â white, American blue-collar workers, for example. These leaders have amplified appeals that blame the global and cultural other for the vulnerability those who were previously privileged may now face.

âWhether it be immigrants that allegedly âtake (y)our jobsâ; corporations who are perceived to enjoy unfair competitive advantages because the countries in which they operate extend financial, legal or other subsidies; or those whose cultural practices seem otherworldly when compared to received wisdom relative to, say, gender, this scapegoating of the cultural and foreign other evokes inchoate feelings some have associated with âtribalismâ both positively and negatively,âEksil and Wood write.

Putin and ErdoÄan represent a wave of autocratic leaders who will continue to push for more power. The more of these autocrats win elections, the more power they gain. The more popular Putin becomes among the right-wing in the United States, the more power politicians like him gain.

âThe more of these autocrats win elections, the more power they gain.â

As right-wing populists-turned-authoritarian leaders, Putin and ErdoÄan share a media image as the ultimate bad boys who wield their anger and macho rhetoric in defense of their nations. The Janus-faced masculinity of Putin and ErdoÄan mixes in the U.S. with the same kind of toxic masculinity at the heart of much evangelicalism. Itâs a dangerous mix.

Supporters of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan rally at a gathering on July 31, 2016, in Cologne, Germany. Cologne and surrounding cities are home to tens of thousands of people of Turkish descent. (Photo by Sascha Steinbach/Getty Images)

Putin and ErdoÄan are also, paradoxically, presented as the good fathers who protect their nations. Somehow the image of being a bad boy becomes a virtue for like-minded supporters.

The bad boy and strong leader is a macho, loud-mouth, bragging, blustering man who threatens, cajoles and berates. In the age of precarity, people are somehow comforted by the idea that this strong man will become the savior.

Bad boys as saviors

This is a dangerous delusion, and Americans are showing a preference for such a leadership style.

Plenty of these transgressive populists are stepping up to claim the mantle of the angry, vengeful, bad boy father figure. No one would have ever guessed that being a bully would become a preferred character trait for a national leader. If transgressive, bullying behavior is ignored or excused, the longer we will face these kinds of challenges to democracy and to shared national values.

For example, when professional golfer Greg Norman recently was asked about the murder of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi, Norman said: “Everybody has owned up to it, right? It has been spoken about, from what I’ve read, going on what you guys reported. Take ownership, no matter what it is. Look, we’ve all made mistakes and you just want to learn from those mistakes and how you can correct them going forward.”

âWhen murder can be downgraded to a mistake, we live in an environment ripe for leaders like Putin, ErdoÄan and other populists.â

When murder can be downgraded to a mistake, we live in an environment ripe for leaders like Putin, ErdoÄan and other populists.

The temptation is to treat bad boy populists as exceptions to the rule, a blip on the old radar screen, or as Roderick Hart puts it, âas an outcropping of larger sociological and political tendencies â growing nationalism throughout the Western world, a renewed testosteronal populism.â

What we canât afford to overlook is that these transgressive leaders are being produced in an atmosphere we have created. The citizens of the world are the ones who create the environment. Putin and ErdoÄan and the others tell us what kind of people we have become. In that case, we are sliding inexorably in the direction of an active fascism where people will surrender their freedom for the false security offered by the bad boy, strong man, father figure.

Recall the Israelites

An archetype for this kind of move has existed forever. Recall the Israelites, back there in the biblical mists, as they made decisions that turned them into slaves of Pharaoh. Walter Brueggemann chronicles how âhungry peasants, in need of food from the monopoly, will pay their money, then forfeit their cattle, and then finally give up their land. ⌠In the end, the peasants are so âhappyâ that they are asked to be âowned.ââ

As the Israelites said at the time, âWe with our land will become slaves to Pharaohâ (Genesis 47:19). This decision led to 400 years of slavery. In our case it threatens to lead to the destruction of democracy.

Steps to power

Prudence demands that we ask how âbad boysâ become national leaders. Eksil and Wood outline how Putin and ErdoÄan came to power. First, they each chose a populist image in their first months and years, casting themselves as men of the people, and as transgressive, angry leaders who would put matters to rights in their respective countries.

Second, they roundly rejected âpoliticsâ and parties in favor of a nativist discourse that castigates outsiders as deficient in terms of their masculinity.

âThey each have played up a male-dominated and conservative set of ideas that appear to restore an imagined and idealized gender order based on male dominance.â

And third, they each have played up a male-dominated and conservative set of ideas that appear to restore an imagined and idealized gender order based on male dominance that will provide stability and âgreatnessâ to their nations. At the same time this has served to undermine and eviscerate public institutions on the grounds of building an apparently more direct line from the father to his people.

ErdoÄan had a temper tantrum at the Davos meeting in 2009. Such behavior has not previously increased a leaderâs support, but in Turkey, there was excitement at ErdoÄanâs tantrum. He returned to Istanbul to cries of âConqueror of Davos!â and praise for his âKasimpasa attitude in Davos.â

The crowd was angry not only over Israelâs Gaza offensive against fellow Muslims, but also over years of being offended by Europeans who thought Turkey did not deserve to join their union. Numerous commentators referred to this blowup as giving Turks a âlost sense of pride,â even comparing his performance to that of Nikita Khrushchev banging his shoe at the United Nations. The public perceived ErdoÄan as expressing the anger of the nation. This transgressive behavior helped reinforce the notion of identification between ruler and nation. ErdoÄanâs anger was not just personal; he was standing in for the nation as a whole. He was viewed as the only man who could protect and defend the country from its enemies, including the corrupt, humiliating West.

âWho are you?â

ErdoÄan made special efforts to portray himself as an authentic leader. âWe are the people. Who are you?â he asked in an aggressive tone, drawing a direct connection between the people and himself as synonymous with the nation. Instead of addressing the corruption charges, ErdoÄan challenged his critics by questioning their credibility and authenticity. By asking âwho are you,â ErdoÄan often criticizes his opponents, including intellectuals and political opponents, as a way of establishing hierarchies between himself as the hero of the people and the allegedly disengaged elites.

âInstead of addressing the corruption charges, ErdoÄan challenged his critics by questioning their credibility and authenticity.â

In Ottoman times, kabadayis, tough guys claiming to be responsible for protecting women and the well-being of the neighborhood from outside bullies, often used this exact expression to start a fight. The kabadayi masculinity has survived, although transformed in Turkish culture today, as Eksil and Wood explain.

The tough guys have returned. While they now whine about being victimized by a feminist culture, their real goal is to seize the power for the old heteronormative values and assert the power of the male over the rest of the culture.

âWho are you?â The echoes of this ancient phrase used to start fights are now heard across America: âWho are you to tell me what to do about pollution?â âWho are you to tell me to wear a mask?â âWho are you?â

Macho country music performer Toby Keith puts the ideology in lyrical form:

Grandpappy told my pappy back in my day son

A man had to answer for the wicked that he’d done

Take all the rope in Texas find a tall oak tree

Round up all of them bad boys, hang them high in the street

For all the people to see

That justice is the one thing you should always find

You got to saddle up your boys, you got to draw a hard line

When the gun smoke settles we’ll sing a victory tune

And we’ll all meet back at the local saloon

We’ll raise up our glasses against Evil forces singing

Whiskey for my men, beer for my horses.

ErdoÄan and Putin are prominent examples of the bad boy transgressive leadership that threatens democracy everywhere. This is why the line has to be drawn in Ukraine and why NATO needs to accept Finland and Sweden as her newest members.

The stakes are too high, because the bad boy ideology grows stronger in the U.S. every day, and it is supported by a Christian nationalism that makes it even more dangerous.

Rodney Kennedy

Rodney W. Kennedy currently serves as interim pastor of Emmanuel Freiden Federated Church in Schenectady, N.Y., and as preaching instructor Palmer Theological Seminary. He is the author of nine books, including the newly released The Immaculate Mistake, about how evangelical Christians gave birth to Donald Trump.

Related articles:

Putin is no Antichrist; heâs worse than that | Analysis by Rodney Kennedy

Choose Life: Putin reminds us how bad theology can turn nuclear | Opinion by Jillian Mason Shannon

How Putinâs picture in a fictitious dictionary challenges all of us | Opinion by Robert Sellers