In the last couple of months, the Black Lives Matter sign that hangs from a post on the front lawn of our church has been vandalized several times. Sometimes the metal sign has been severely bent. Other times, someone has written extremely racist and violent messages on its surface. From my experience working with the staff and congregation to address this vandalism, I’ve learned several lessons:

In the last couple of months, the Black Lives Matter sign that hangs from a post on the front lawn of our church has been vandalized several times. Sometimes the metal sign has been severely bent. Other times, someone has written extremely racist and violent messages on its surface. From my experience working with the staff and congregation to address this vandalism, I’ve learned several lessons:

BLM vandalism is a form of violence. Period. We should get clear about that. While it doesn’t attack a flesh-and-bone body, it is a discursive form of violence that operates through language and symbol to draw upon the power of a long legacy of white supremacy to attack the psyches and souls of Black people and, albeit to a lesser degree, demoralize white folk who would dare vocally and visibly counter this legacy. To view BLM vandalism like you would view any ol’ instance of property destruction misses the message being communicated by an attack on this particular symbol of solidarity with Black people standing against police violence, mass incarceration, and the many other forms of structural racism in our country.

BLM vandalism is a form of violence against individuals. When the vandalism started, I was first focused primarily on what messages were being communicated to black members of our surrounding community. It was one of the African-American members in my own congregation who helped correct my farsighted gaze. It quickly became clear to me and other white members of the congregation that when this happens on the front lawn of your own church, it is foremost an act of violence against Black members of the congregation who arrive at their own sacred sanctuary to a message of racist violence they must pass in order to enter their own church doors.

BLM vandalism is a form of violence against individuals. When the vandalism started, I was first focused primarily on what messages were being communicated to black members of our surrounding community. It was one of the African-American members in my own congregation who helped correct my farsighted gaze. It quickly became clear to me and other white members of the congregation that when this happens on the front lawn of your own church, it is foremost an act of violence against Black members of the congregation who arrive at their own sacred sanctuary to a message of racist violence they must pass in order to enter their own church doors.

BLM vandalism should not be simply and immediately hidden. We too often hide the evidence of racist violence so that our consciences can be assuaged and we can imagine that “those things don’t happen here.” It was an activist in our community who helped me to see the importance of letting our surrounding community — especially white people — see just what is happening here in one of the most educated and erudite zip codes in the country (Harvard Square). While some of the vandalism was too explicitly violent to leave visible, we allowed other instances of defacement to remain observable for a number of days.

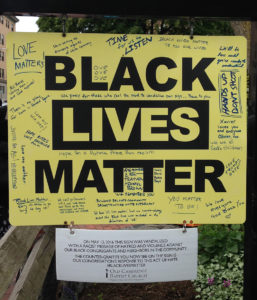

Finally, the congregation engaged in creative resistance to take the power of vandalism out of the hands of the vandals: we graffitied our own sign. We ensured that every blank space on the sign was filled with messages of love, support, justice, and solidarity with the BLM movement. We also hung a smaller sign beneath it explaining the history of vandalism to our sign, contextualizing the congregation’s counter-graffiti response.

BLM vandalism is not indicative of a problem with the #BlackLivesMatter movement or its message. I continue to hear white people critique our sign and the larger movement by railing against the particularity of the sign’s message. The oft-cited phrase parroted in contradiction to the BLM sign is, “All Lives Matter.” I doubt anyone displaying a Black Lives Matter sign would disagree that all lives do, indeed, matter. But we share a history in the United States that has perpetuated the message (spoken and tacit) that Black lives matter significantly less, including the nearly 250 years of African enslavement, lynching, Jim Crow, the New Jim Crow (imprisonment of African Americans at six times the rate of whites), and the death of innumerable unarmed Black people at the hands of police. Thus, displaying the BLM sign is a small sign of visual solidarity with our black friends, neighbors, and congregants as we work for racial justice. Defacement of BLM signs is a violent reaction to a small act of public recognition that white people have not usually behaved as though black lives actually do matter to us.

BLM vandalism is not indicative of a problem with the #BlackLivesMatter movement or its message. I continue to hear white people critique our sign and the larger movement by railing against the particularity of the sign’s message. The oft-cited phrase parroted in contradiction to the BLM sign is, “All Lives Matter.” I doubt anyone displaying a Black Lives Matter sign would disagree that all lives do, indeed, matter. But we share a history in the United States that has perpetuated the message (spoken and tacit) that Black lives matter significantly less, including the nearly 250 years of African enslavement, lynching, Jim Crow, the New Jim Crow (imprisonment of African Americans at six times the rate of whites), and the death of innumerable unarmed Black people at the hands of police. Thus, displaying the BLM sign is a small sign of visual solidarity with our black friends, neighbors, and congregants as we work for racial justice. Defacement of BLM signs is a violent reaction to a small act of public recognition that white people have not usually behaved as though black lives actually do matter to us.

BLM vandalism is indicative of larger structures of violence and the denigration of black bodies. BLM vandalism does matter for all of these reasons, but it’s not what matters most. For predominantly white congregations who take racial justice seriously, we’ve got our work cut out for us in addressing legacies of white supremacy institutionalized in our organizations and organizing the structures of our collective consciousness. Racial disparities in the criminal justice system, the exponentially higher rates of hate crime violence against LGBTQ people of color in comparison to white LGBTQ people, police violence against unarmed black people, the rise in racist political rhetoric and publicly visible racist attitudes — all of these realities and more stand behind the BLM sign on my own church lawn as the real work of justice that we have before us to do.

Another congregant reminded me this week that behind each Black Lives Matters sign on church lawns all around the U.S. is a community of people who are committing themselves to the work of racial justice. And there are not enough vandals in the world to break the spirit of this movement of Christians following the trail of peace and justice blazed for us by our brown-skinned savior.