There is a growing trend among Southern Baptist churches to adopt an elder-based model over the traditional congregational model.

In Baptist churches, the concept of elder-led polity refers to a specific form of church governance where elders play a central role in decision-making and spiritual leadership. A small group of men — it’s almost always only men — are selected, elected or appointed to govern the life of the church. Some elements of congregationalism are retained in the elder model.

The more traditional model in Baptist churches in America has been pure congregational governance, a small-d democracy. Through the use of committees and deacons and sometimes church councils, all important decisions for the church are made by the congregation at large.

Now, however, a growing number of Southern Baptist churches are joining Bible churches and nondenominational churches — leaving behind pure congregational governance and naming elders to set the direction and do the business of the church.

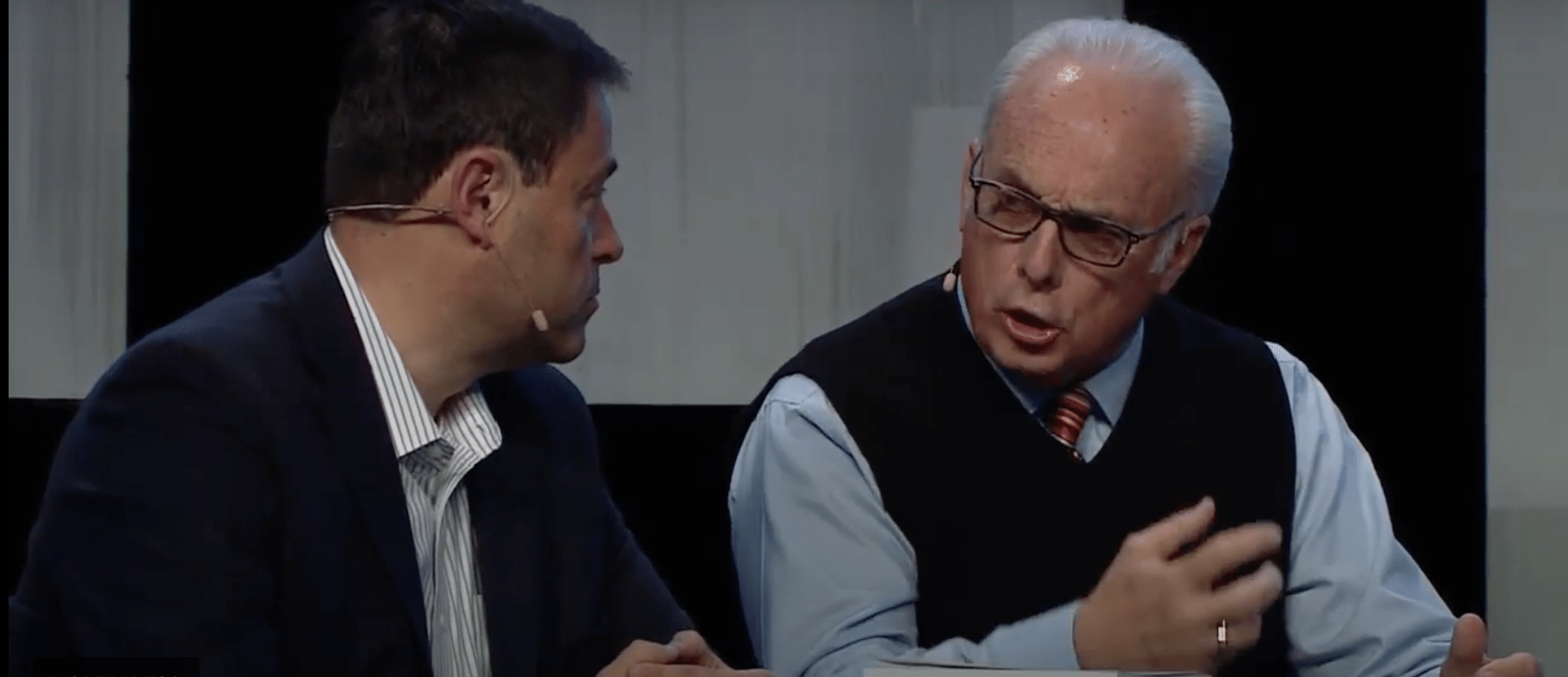

Mark Dever (left) on stage with John MacArthur at the 2014 Together for the Gospel conference.

Biblical evidence

Those touting the elder model appeal to Scripture as justification. The biblical material flowing from the word “elder” in the New Testament is extensive. The word appears 53 times in the New Testament and variously refers to pastors, bishops and church leaders.

And the debates around the meaning of “elder” are a bewildering stack of information. Much of the attention is given to 1 Timothy 5:17–22, which assumes the reader knows about the office of elder. The same could be said of other New Testament references to elders, a word and a role modern-day theologians debate without wide consensus.

However, among conservative Calvinistic churches there is common agreement, which explains the infiltration into Southern Baptist churches in the past 30 years as a resurgent Calvinism has spread as a byproduct of the “conservative resurgence.”

A chief proponent of elder-ruled churches is John MacArthur, pastor of Grace Community Church in Los Angeles. His church’s website devotes an entire section to the topic of “biblical eldership.”

The page quotes MacArthur: “The consistent pattern throughout the New Testament is that each local body of believers is shepherded by a plurality of God-ordained elders. Simply stated, this is the only pattern for church leadership given in the New Testament. Nowhere in Scripture does one find a local assembly ruled by majority opinion or by a single pastor.”

Leaders on the platform at the SBC annual meeting in Anaheim, Calif., vote on an issue by lifting their ballots.

The attraction of the elder model

Apart from the conviction that elder rule is the “only pattern for church leadership,” the concept finds appeal for other reasons as well.

The elder model elevates the role of the senior pastor. He assumes a CEO position. He accepts the mantle of authority with a board of directors. He serves as one of the small group of elders and usually has outsized influence there.

If a preacher prefers order and a certain calmness, the messiness of congregationalism can be a problem. Pastors have experienced problems, church fights and dissension in monthly or quarterly church conferences. The number of pastors who have been victims of bad church governance is large.

From this perspective, the desire for a more predictable model of governance can be attractive to pastors of all theological stripes. A desire for order and a less argumentative church culture seems a desirable outcome.

But does the elder model represent a genuine and needed correction to Baptist congregationalism? Has the neo-Calvinistic influence among Southern Baptists given life to groundbreaking polity of the sort that will revitalize churches?

The advocates of the elder model certainly believe they have accomplished the goal of transforming weak, failing congregations overwhelmed by the messiness and lack of discipline in the congregational polity system.

Baptists versus Presbyterians

Another influential Baptist pastor advocating the elder model is Mark Dever, pastor of Capitol Hill Baptist Church in Washington, D.C.

Speaking in 2004 at a conference sponsored by the Baptist Center for Theology and Ministry of New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, Dever argued a body of elders is the New Testament model of church structure. Yet he made a clear distinction between being “elder-led” and “elder-ruled,” flatly rejecting the Presbyterian model that distinguishes between teaching elders and ruling elders. Instead, Dever offered a biblical argument for an elder-led form of congregationalism in which the congregation serves as a “final court of appeal” in the decision-making process.

MacArthur notes that the view of church governance he and Dever hold is sometimes a tough sell to modern churches.

He writes: “Because of its heritage of democratic values and its long history of congregational church government, modern American evangelicalism often views the concept of elder rule with suspicion. The clear teaching of Scripture, however, demonstrates that the biblical norm for church leadership is a plurality of God-ordained elders, and only by following this biblical pattern will the church maximize its fruitfulness to the glory of God.”

The connecting point between Presbyterians and some Baptists is, of course, Calvinism.

The connecting point between Presbyterians and some Baptists is, of course, Calvinism. But it’s really more complicated than that.

Long before he was elected Southern Baptist Convention president, Bart Barber wrote a post on “pastors and presbyters” that highlighted the very trend of changing church governance models in Baptist churches.

In 2014 he wrote: “But something else has been happening in the Southern Baptist Convention — something that has not appeared on the agenda of any of our annual meetings — that will also figure prominently in our recollection of this moment in our history. This is the era when Southern Baptist churches in large numbers began to change the governance of our churches. This is the day of the ‘elder-led’ movement in the Southern Baptist Convention.”

Congregationalism “held sway over Southern Baptist life for a century and a half,” he observed.

Then he cited “the rise of the New Calvinism” as one important factor in the contemporary change. “Groups like Mark Dever’s IX Marks have championed the transition to elder governance as an important means to increasing church health. Other groups among the New Calvinists, even if they have not been as focused on ecclesiology as Dever’s group has been, have lifted up a number of Presbyterian or presbyterial voices as heroes to younger Southern Baptists. The correlation between the elder-led movement and the New Calvinism is tight (although Southern Baptists from more than one soteriological viewpoint are embracing the elder-led option), and when the soteriological pendulum swings the other way, the most lasting impact remaining upon Southern Baptist churches by this movement may very well be the structural changes that it made to local churches by means of the spread of elder-led polity.”

While Barber acknowledged the obvious appeal of elders to some Baptists, he also warned of dangers: “I predict that the stories of bad Presbyterianism that will come out of this new polity in Southern Baptist churches will make the old stories of bad congregationalism look like a church picnic.”

I join Bart Barber in raising concerns about some dangers of elder-led Baptist congregations.

The elder model diminishes the democratic spirit

The Baptist way lives and breathes democracy. In the preface to Bill Leonard’s Baptist Ways, Edwin S. Gaustad puts it exactly right: “Ecclesiastically speaking, the ultimate authority in Baptist life is the local church. … So this ‘congregational polity’ produces a democracy – and much noisy confusion. Baptists are free agents, and their churches are free spirits.”

“The Baptist way lives and breathes democracy.”

A congregational model resembles the original Athens, Greece, model of democracy. James Miller, in Can Democracy Work, describes the original democracy in Athens: “In classical Athens, democracy presupposed shared norms, a shared religious horizon and a shared projection of egalitarian ideals; it revolved around periodic public assemblies in which all the citizens met as one and had, as its characteristic procedure, the random selection of citizens to fill almost all the key offices of justice, administration and government.”

In the 20th century, Southern Baptists identified with this kind of democratic governance, yet Dever and MacArthur and Mohler now contend that is not a “biblical” model.

Democracy always has struggled to find acceptance. According to James T. Kloppenberg in Toward Democracy, for centuries, “democracy” was a term of abuse, usually yoked with labels such as “rabble,” “herd” or “mob.”

Kloppenberg perceives democracy as rooted in deliberation, plurality and reciprocity. The elder-led or elder-ruled model inhibits all the basic principles of democracy. Since all elders are men, the voice of women is diminished even more. The elder model reinforces the increasing strictness within the SBC of not ordaining women as pastors. This suggests the elder movement could have more to do with the role of women than with Calvinistic theology.

The elder model raises more questions about authority than it answers

Although Barber cites concerns to the contrary, the elder model increases pastoral authority.

The drumbeat of the conservative movement in the SBC always has been dominated by authority. There has been an incremental progression among Southern Baptists toward authoritarianism.

In the 1980s the issue was biblical authority. The Bible must be inerrant and literal. Once this basic authority was established, authority was extended in more restrictive ways over women. Then it was extended to sexuality and gender.

“The drumbeat of the conservative movement in the SBC always has been dominated by authority.”

The elder model provides a greater authority to the pastor and to a small group of men.

Authoritarianism appeals to people who are not at home with ambiguity, contingency and complexity: there is nothing intrinsically “left-wing” or “right-wing” about this instinct at all. It is anti-pluralist. It is suspicious of people with different ideas. It is allergic to fierce debates.

The elder model diminishes the role of argument and dissent

The primacy of argument as a Baptist distinctive is replaced with a hierarchy of required beliefs. There are fewer opportunities for congregational dissent, fewer voices involved in decision-making, and an overt hostility to anyone not in conformity to the status quo.

This suggests something less than Baptist now exerts influence over the historical Baptist love of argument. I grew up with an old saying, “Where two or three Baptists are gathered, there’s at least four opinions.”

Dissent as a method of Baptist discovery is an overall “good” Baptists have offered the larger church. It contains the ability to cultivate democratic disagreement as a vehicle of a more egalitarian politics. Democracy exists only in the presence of dissent. Yet democratic dissent is rendered oxymoronic in a Southern Baptist system of increasing authority.

Sustaining a Baptist church in our complex world requires a commitment to collective arguing and dissenting as the natural tools for deliberation and decision-making. These practices are foundational to upholding values of toleration, personal autonomy, individual rights, pluralism, distributive justice and religious neutrality.

An ongoing debate

The debate over congregational democracy versus elder-based authority and autonomy will continue. Whether the outcome will be as efficacious for conservatives as their 1980s resurgence remains undetermined. The debate exposes the serious differences between regular conservative Southern Baptists and Calvinist Southern Baptists.

Working out these issues could lead to a better understanding of what it means to be Baptist. And in this debate, the people sitting in the pews — if given a vote — may produce a revival of dissent from authoritarian pastors, elders and leaders.