Your friendly neighbor epidemiologist wants you to know that when it comes to understanding COVID-19, faith and science do not have to be in conflict.

Emily Smith

“Friendly neighbor epidemiologist” is the title Emily Smith has given to a Facebook page and blog she’s created during the pandemic to address questions from friends and family — detailed content that is now reaching far beyond her inner circle. She is, indeed, an epidemiologist. And she wants to talk to anyone who will listen in her naturally friendly tone, like talking to a really smart neighbor who just might be the nicest person you ever met.

Smith is assistant professor of epidemiology at Baylor University. She also remains on faculty at the Duke Global Health Institute, where she previously taught. She has a Ph.D. from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and she’s got a lengthy list of publications and citations to back up her expertise. She’s also married to a Baptist pastor and is the mother of two young children.

Galatians and Good Samaritan

When it comes to COVID-19, Smith intuitively blends her professional training with her Christian faith. Thus one of her most-read and most-challenged posts draws on a passage from Galatians 5: “It is for freedom that Christ has set us free … for you were called to be free. Only do not use your freedom as an opportunity for the flesh, but through love serve one another. For the entire law is summed in this: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’”

She wrote: “Without Jesus, the tools of wearing a mask and staying home can feel like an infringement of freedom. However, when we let Jesus redefine freedom according to the greatest act of selfless love at the Cross, perhaps our witness is more than we could have ever imagined.”

The good doctor blends Galatians 5 with Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan and her knowledge of how the virus spreads to say that “one of the greatest acts of love” Christians can do is to stay home from in-person worship.

The good doctor blends Galatians 5 with Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan and her knowledge of how the virus spreads to say that “one of the greatest acts of love” Christians can do is to stay home from in-person worship.

That message went down easier at the beginning of the pandemic than it does today.

“At the beginning, people just said thank you and by and large were appreciative of trying to figure out what the pandemic was,” she said in an interview late last week. “The further we’ve gotten into it, there is a significant divide on people who are posting. I have to delete or hide most of them, because that is not the battle we are facing.”

The battle, she believes, is a global health threat. But critics see only a threat to their freedom of religious expression.

Being a friendly epidemiologist, Smith described the criticism only as “significant pushback” and admits someone labeled her advice “part of the mark of the beast,” a reference to the book of Revelation and the end-times. “We had a nasty letter in our mailbox.”

“The backlash is coming from the faith community by and large,” she said with sadness. “It’s being misinterpreted that I’m taking away freedom. I’m only trying to redefine that freedom to the Good Samaritan.”

Faith and science

At the root of this conflict is a perceived clash between faith and science — a conflict she absolutely rejects: “Faith and science are not incongruous to me.”

“That caught people by surprise because I’m a scientist and pastor’s wife and go to a Baptist church,” she explained. “There’s a weird thing that faith has to be full of emotion and things we can’t see and a whole lot of prayer. I do all those. But there’s also a notion that if we are God’s workmanship made in advance to do good works, part of that work is being the best scientist I can be.”

“The value of epidemiology is figuring out who are the most vulnerable and helping them.”

And to her, that is a spiritual calling: “The value of epidemiology is figuring out who are the most vulnerable and helping them. If we do the science well, we can help the most vulnerable.”

Prior to the pandemic, the most vulnerable she tended to work with and teach her students about live half a world away, mainly in Africa. She has done extensive research in Somaliland and Uganda.

Most of the examples her students have seen in their global health studies have not been people from their own communities, she said. Until now. “To be right at their front door, they’re grappling themselves with this. It’s no longer a world of they versus us, the U.S. versus everyone else.”

Follow the data

As classes resume at Baylor this week, she predicts she’ll get “a little more to call out the value of data.”

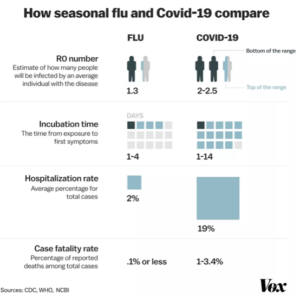

Smith’s blog is full of charts like this and explanations about what they mean.

And the threat of COVID is clearly illustrated by data, Smith said.

The opposition to these facts “does not make sense to me when the data clearly show this is not the flu, that certain communities are being decimated by the virus and dying younger than more of the richer areas. To come against a public health system that is made for the health of the public in the name of Jesus seems to be counter to the work of Jesus.”

Back to the Bible, she’s been thinking lately of Jesus’ temptation in the wilderness, when Satan wants Jesus to jump off the temple so angels can rescue him. And Jesus says no. “To me this is not a culture war of going into a physical building,” she said. “The virus is not going to stop at the doors of a church and then not stop at the doors of a bar. It doesn’t work like that.

“What are we really fighting against? I’m not fighting to keep bars closed. I am fighting to represent Jesus well by taking care of the people most in need. I think we have lost the perspective of what Jesus calls us to do.”

Advice to churches

Baked into this discussion is a fair amount of economic and racial privilege, she explained. While it is true that more affluent white communities have not experienced the worst of the virus, the residents of those communities depend on more vulnerable people to serve them when they do go out.

“If we go to church and go out to eat at Cheddar’s afterward, who is taking care of us and what health care do they have?” she said. “Or think of the janitorial staff at your church who have to go to clean the church after we go there.

“What we do matters,” she emphasized. “So just for a time — this is not going to be forever — stay home.”

Her advice to pastors and church leaders in most places — with a few exceptions that she outlines in one of her posts — is to shut down in-person worship and activities until a vaccine is available. “By shut down, I mean physically. The church can go on. It’s a small inconvenience for protecting others.

“When we do it online, it helps people who can’t do their jobs online. That includes our essential workers.”

“Go home and do it all online,” Smith urged. “When we do it online, it helps people who can’t do their jobs online. That includes our essential workers. Church can be done in a home, which is where it started in Acts anyway.”

Pastors who have caught this vision of protecting the community “have seen their giving go up and they’ve become innovative and cared for people in ways they never had before,” she asserted. “We have never done this before. In our lifetimes we haven’t seen anything like this before. I urge people to breathe a little bit more before they jump to conclusions.”

That same message applies to Christians who care about evangelism, Smith said. “I think we’re missing the harvest. At the beginning most churches were surprised who was coming to church online. People who were hurt or left out came to church. … Those are things we’re missing when we’re so set on being physically in a building. Maybe we’re missing (the opportunity) God is putting right in front us.”

An index to the various pandemic topics Smith has addressed on her Facebook page may be found here.