“The Black church will be the salvation of the world.” I’ll never forget those words, uttered by a colleague of mine as we gathered for a meeting of the local Black Pastors alliance.

They struck me as soon as they left his lips, and I also distinctly remember looking around the room and seeing the discomfort among some of my fellow Black pastors. It is ironic, of course, that Black pastors gathered for a meeting of an alliance specifically and intentionally formed to support Black pastors would be disturbed by such a remark; but of course, like all other pastors, we have been fed the lie that God “does not see color” for so long (even while depictions of that God were exclusively white for centuries) that such a comment makes even us uneasy.

Paul Robeson Ford

But the uneasiness is also a reflection of the fear that such an assertion publicly made will lead to accusations of “reverse racism” or that the church has given in to “identity politics.”

These critiques are part of the same family of racially obtuse mindsets that have led the Southern Baptist Convention to wage war on Critical Race Theory, a 30-year-old analytical tool that makes no claims to transcendent knowledge but simply “tells it like it is” with regard to how race has and does operate in this society, and how it permeates nearly every structural and institutional relationship that exists in society. The upcoming presidential election in that convention will determine what direction they take in this ill-conceived battle, even as their Black pastors and churches head for the exit.

Part of the reason why I will never forget those words is because they resonated with me at a deep level. My colleague was right. The Black church can be the salvation of the world, and the only thing that will stop that from taking place is for groups like the SBC to remain steadfast in their racial arrogance and defensive obtuseness.

The reason why the Black church can and will be the salvation of the world is not because black or darker-than-white skinned people predominate those spaces. It is not an issue of skin color. It is an issue of lived human experience, and the legacy of oppression juxtaposed against resistance, and suffering juxtaposed with perseverance, that has provided our people with a unique testimony of how God saves God’s people in history, and what salvation looks like in the real world.

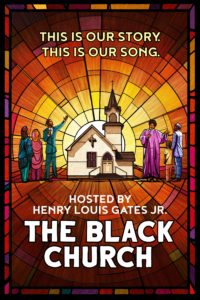

Henry Louis Gates gestured toward much of this legacy in his highly acclaimed documentary on the Black Church that aired last week. While there has been plenty of “insider critique” amongst Black church historians and practitioners about what more should have been said, or what stories he did not get quite right, the documentary made one thing clear: The Black church is a gift to the body of Christ, and it should be received as such by all people, but especially by white people. It was in the crucible of oppression that the Black church was born, and it was in the crucible of oppression that the Black church found — and will continue to find — its identity.

Henry Louis Gates gestured toward much of this legacy in his highly acclaimed documentary on the Black Church that aired last week. While there has been plenty of “insider critique” amongst Black church historians and practitioners about what more should have been said, or what stories he did not get quite right, the documentary made one thing clear: The Black church is a gift to the body of Christ, and it should be received as such by all people, but especially by white people. It was in the crucible of oppression that the Black church was born, and it was in the crucible of oppression that the Black church found — and will continue to find — its identity.

Albert Cleage asserted decades ago that “nothing is more sacred than the liberation of Black people.” His claim was based on a now well-established premise that God has a preferential option for the poor and oppressed and that — in the United States of America, at least — means Black people. It also, of course, means American Indians and Hispanic immigrants and those whom Howard Thurman described as “living with their backs up against the wall.”

Nothing is more sacred than liberating those who are the most marginalized and the most separated from the worldly prosperity that other people experience because of inherited privileges and racial or class-based stratification.

While the history of the Black church reveals an ongoing — and still unsettled — debate about what are the most effective means to achieving liberation, there is no question that this concern has been central to its institutional life. And if white America wants to learn how to free its Christian religion from white supremacy, then it needs to counsel the increasingly accepted wisdom of following Black leadership, especially that leadership that remains invested in (or at least in close contact with) the institutional Black church.

Despite claims to the contrary, the Black church is not dead and is not going to die anytime soon. There are thousands of thriving historically and predominantly Black congregations all over the country (not to mention many more around the world). And what the Black church — in all its complicated glory — can offer this nation now is a way out, a path forward.

“Despite claims to the contrary, the Black church is not dead and is not going to die anytime soon.”

We know what it means to confront the truth of racism head on, because we have been doing it from our pulpits for more than 200 years. We know what it means to struggle while trying to hold in tension God’s demands for us to repent but also to reconcile and forgive — because we have been doing that for more than 200 years as we deal with the treachery of oppression.

We know what it means to build and sustain an institution almost entirely on the power of the grassroots, because we have been doing it for more than 200 years without the benefit of massive wealth and privilege to leverage. We know what it means to exist and survive and even thrive in spite of deep disagreements over wedge issues like human sexuality and the role of women in institutional life, because we have been dealing with it — in one form or another — for more than 200 years; we’re still standing, and we are pressing forward.

Carlton A.G. Eversley

The late Carlton A.G. Eversley, a longtime Black Presbyterian clergyman, used to declare that “everything good you can say about the Black church is true, and so is everything bad you can say about the Black church.” He was right on both accounts, and in our best moments, we have leveraged the lessons of the dark past — the “bad” about our institution — to build a better future that accentuates more of the “good.” We have been able to do it because we have been believers, our faith has been refined in the fire of injustice, and we never have lost sight of the politics of Jesus (although in some moments we bowed to pressure to set those politics aside).

Many of us are ready to share those lessons; we are ready to share the stories of that struggle; and we are ready to share the witness of that enduring faith with the world. But we will not sit at tables where we are not welcomed as part of the family, and we will not speak were it has been made clear that our voice does not matter. We are ready to step up and take our rightful place in the vanguard that will bring healing and hope to a distressed and dying world.

The question for the world is a simple one: Are you ready for us?

Paul Robeson Ford serves as senior pastor of First Baptist Church (Highland Avenue) in Winston-Salem, N.C. He was born and raised in New York City and grew up at the Riverside Church under the leadership of James A. Forbes Jr. He received a master of divinity degree from the Divinity School at the University of Chicago, where he is now a candidate for the Ph.D. in theology.

Related articles:

SBC seminary presidents meet with Black pastors but don’t change position on Critical Race Theory

Southern Baptists need a vaccine for racism

Could you win a quiz show by defining ‘Critical Race Theory’?

Southwestern president says SBC seminary leaders have been ‘misunderstood’ and ‘misconstrued’

SBC seminary presidents are ‘complicit with evil,’ revered California pastor says

SBC seminary presidents are propagating fear to maintain control | Laura Levens

Is it time for Black Christians to give up on the SBC? | Corrie Shull