In a case little heralded outside North Texas and outside Episcopal Church insiders, the United States Supreme Court in February opened the door for more litigation nationwide over disputed church property as churches split over social issues such as women in ministry and LGBTQ inclusion.

The case, All Saints’ Episcopal Church v. Episcopal Diocese of Fort Worth, has particular application for mainline Protestant denominations that assert corporate ownership of church property — such as the Presbyterian Church (USA) and the United Methodist Church.

And while Baptists and others in the free-church tradition based on local church autonomy might see the Texas events as irrelevant, the root legal problem identified could come into play in virtually any congregation that splits and has a dispute over property.

The root legal problem identified could come into play in virtually any congregation that splits and has a dispute over property.

This case was deemed so important that although it involved only Episcopal congregations, a coalition of Presbyterians, Methodists and others joined in petitioning the U.S. Supreme Court to address the underlying legal debate, not just the current case.

However, the U.S. Supreme Court on Feb. 22 declined to take on any part of the issue — leaving in place a patchwork of state-by-state regulations that likely will continue to produce uneven outcomes. And by refusing the case, the high court left in place a ruling by the Texas Supreme Court that awarded $100 million in property to a breakaway Episcopal group in Fort Worth, Texas.

That meant that the week of April 19, members of five North Texas Episcopal churches had to vacate their buildings and turn over the keys to a group of dissidents that several years earlier had broken with the national denomination over the ordination of women priests and the inclusion of LGBTQ Christians.

Former sanctuary of St. Luke in the Meadows Episcopal Church in Fort Worth.

“Today is our last worship in the building that has housed St. Luke’s in the Meadow for more than 75 years,” wrote Episcopal lay leader Katie Sherrod on Facebook April 18. “For one last time we will celebrate the all-encompassing, unconditional love of God for all humanity. We will walk out of there carrying with us the memories of the hundreds of faithful lay people and clergy who built it up for mission and ministry of the Episcopal Church.”

“We grieve that this building, made holy by the love it housed, will now be in the hands of those who believe women are not proper matter for ordination and that LGBTQ people are somehow disordered,” added Sherrod, a veteran journalist who serves as communications director for the Episcopal Church of North Texas. “We will pray for them. But St. Luke’s in the Meadow will carry on, ministering to our neighbors, all of them, no exceptions. If the cost of inclusion is to lose our buildings, so be it. We will move forward, holding on to one another and to God. Pray for us.”

How did this happen?

As with most church fights, there’s a back story here. It’s a story rooted in the same cultural divisions that are rending the fellowship of churches of all kinds: gender and sexuality.

While the Episcopal Church in America has taken a more liberal route that includes ordination of women as priests and inclusion of LGBTQ persons in most aspects of the church’s life, those views have not been universally accepted. On a diocese by diocese and congregation by congregation basis, different decisions have been made.

The Episcopal Diocese of Fort Worth offers one of the clearest examples of this division. Unlike its larger neighbor 30 miles east, Fort Worth remains far more conservative politically and culturally than Dallas. That conservatism has been evident within the region’s Episcopal churches as well.

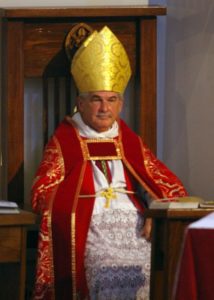

Jack Iker

By the dawn of the 21st century, the Episcopal bishop of Fort Worth, Jack Iker, was considered one of the most conservative bishops in the nation. He was reported to be the only such bishop opposing the ordination of women as priests.

Things got more heated when in 2004 Gene Robinson, an openly gay man, was named Episcopal bishop of New Hampshire. And then in 2006, Katharine Jefferts Schori was elected presiding bishop and primate of the Episcopal Church in America, the first woman to hold such a position.

Within two years, the Episcopal Diocese of Fort Worth voted to leave the denomination, fueled by Iker and his appointees who continued to hold more conservative views than the national leadership. The national body did not recognize the Fort Worth group’s decision, claiming it is not possible for a diocese to leave the fold because of the connectional nature of the denomination’s polity. Jefferts Schori revoked Iker’s credentials.

Katharine Jefferts Schori

That set off years of litigation, with two competing groups claiming to be the legitimate Episcopal Diocese of Fort Worth — even going by the same name.

Iker remained bishop of the breakaway diocese until his retirement in 2019, when he was succeeded by Ryan Reed. The national church named Scott Mayer as provisional bishop of what it considered to be the legitimate diocese. Mayer also serves another Texas diocese as bishop.

The Iker-led group became a founding member of a new transnational body called the Anglican Church in North America — a name that plays to the roots of the Episcopal Church in the Anglican communion created when Henry VIII broke from the Roman Catholic Church to create the Church of England. “Anglican” is a more all-encompassing label than “Episcopal,” which has been used most widely in the United States.

The property dispute

With two competing dioceses claiming leadership over the Episcopal congregations of the Fort Worth region, a practical matter quickly arose: Who owned and had the right to use the various church properties?

Unlike Baptists and others in the free church tradition where local congregations own and manage their own properties, the Episcopal Church claims title to all its affiliated church properties. The same is generally true for Methodists and Presbyterians, which also has led to similar disputes in recent years.

For example, in Dallas, Highland Park Presbyterian Church in 2014 agreed to pay a regional body of the Presbyterian Church (USA) $7.8 million — which was calculated to be 11% of the fair market value of the $70 million property — to keep its buildings after leaving the national church for reasons similar to the Episcopal divide in Fort Worth.

The sanctuary forfeited by All Saints Episcopal Church.

Back in Fort Worth, the original diocese currently has 15 congregations, including eight that found new locations after the breakaway group claimed ownership of their former church buildings. The property disputes came down to five highly contested by the congregations who believed the more conservative group was stealing their property: St. Christopher’s, St. Luke’s in the Meadow, St. Elisabeth’s & Christ the King, and All Saints in Fort Worth, and one congregation, St. Stephen’s, in Wichita Falls.

About two dozen congregations aligned with the breakaway group have retained possession of their church buildings. What will happen to the five properties now being turned over to the victorious group is unclear, as those who have remained worshiping there do not favor the conservative group and are vacating the premises.

Suzanne Gill, spokesperson for the conservative Fort Worth diocese, told Spectrum News that Bishop Ryan Reed plans to reopen the empty churches as soon as possible and that all who desire to worship will be welcome.

The court cases

The split in the Fort Worth diocese prompted litigation in the civil courts that has yo-yoed back and forth with a victory for one side and then for the other, finally landing in the Texas Supreme Court, which is made up of nine Republican judges in a state government system dominated by social conservatives. Texas is one of the few states in the nation that holds partisan elections for its state Supreme Court seats, creating one of the most partisan state high courts in the United States.

Typically, civil courts refuse to engage in disputes over church doctrine or polity. But in this case, the courts took on the matter while claiming it could be considered on “neutral” grounds that do not involve theology or doctrine.

The courts took on the matter while claiming it could be considered on “neutral” grounds that do not involve theology or doctrine.

The Episcopal Church argued that a portion of its church law known as the Dennis Canon says that church property is held in trust for the national church and therefore does not belong to the congregations. Iker and his group argued that the properties belong to the diocese, which means them. After several twists and turns, the Texas Supreme Court in May 2020 ruled that Texas law allows a trust to be revoked and that Texas law supersedes canon law, awarding the properties to the Anglican group.

Critics of the Texas court ruling expressed alarm that the high court applied the law as if the church were a corporation, not a church.

Sherrod told Spectrum News that this should concern other churches with hierarchal polity: “I have a hard time explaining this because they tied themselves into legal pretzels to be able to do this. They decided that churches are businesses. If they’re businesses, then the board of directors can vote to do whatever they want.”

And, she said, the Texas high court’s decision appears to her to be politically motivated.

“When we were down in Austin before the Supreme Court, one of the judges started quoting the Bible at us,” she said. “They would talk a lot about the gay issue and stuff. We would talk about the law, the fact that this was a church and who gets to decide who the Episcopal bishop of Fort Worth is.”

Spectrum News further reported that the Texas outcome stands alone: “In at least three other dioceses around the country facing the same legal battles — cases in which a conservative faction of the church split and then claimed the rights to their property — courts have sided with the national church. Texas is the only place where the courts awarded property to the splinter group.”

“Texas is the only place where the courts awarded property to the splinter group.”

And yet, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to take up the case. That concerns other religious leaders not just because they disagree with the outcome but because they believe a larger legal issue was left in limbo.

Why this matters

Before a 1979 U.S. Supreme Court case called Jones v. Wolf, the court deferred to a church’s own resolution of its property disputes as a First Amendment protection. In Jones, however, the court allowed other approaches by saying a state “may adopt any one of various approaches for settling church property disputes so long as it involves no consideration of doctrinal matters, whether the ritual and liturgy of worship or the tenets of faith.”

The friend-of-the-court brief filed with the U.S. Supreme Court by the Presbyterian Church (USA), the United Methodist Church and others explained their reason for weighing in on the matter: “We believe that deference to religious organizations’ decisions regarding internal structure, organization, and hierarchy is paramount to maintaining religious liberty and separation of church and state.”

And that has not been the case ever since the Jones ruling, the religious leaders said.

“State courts have taken widely divergent approaches in deciding church-property disputes based on purportedly neutral principles of law. As a result, some courts still provide substantial deference to a church’s internal resolution of property disputes, while other courts afford virtually no deference to the church’s views. But regardless of how courts interpret Jones, one thing is apparent: The neutral-principles approach has not allowed courts to adjudicate church-property disputes free from entanglement in questions of religious doctrine and polity.

Related articles:

We lost our church today | Opinion by Wende Dwyer-Johnsen