One of the growing frustrations many deconstructing Christians, ex-evangelicals, liberationist and liberal theologians share is how conservative organizations like The Gospel Coalition constantly misrepresent us through “straw man” fallacies.

In the field of logic, a “straw man” is when somebody twists or exaggerates another person’s position and then argues against the distortion.

In recent years, theological conservatives have gone beyond simply distorting the positions of Christians they consider to be liberal, but have gone so far as to criticize the empathy and compassion that more liberal Christians have.

Rick Pidcock

As conversations have been picking up nationally about conservatives criticizing empathy, TGC tweeted an article on Aug. 28 by Dan Doriani against “Friendly Theological Liberalism: A Threat in Every Age.” Doriani is a theology professor at Covenant Theological Seminary, which is affiliated with the Presbyterian Church in America.

What quickly becomes clear, however, is that Doriani either has no knowledge of theological liberalism or no willingness to define it accurately. Here are four ways Doriani misrepresents those he would define as theological liberals.

The goal of liberalism

In his introduction, Doriani says, “The liberal theologian’s goal is to rescue Christianity by excising the elements that seem most offensive in that day. In one era, the doctrine of sin is unacceptable; in another, it’s miracles; in another, it’s the virgin birth, the substitutionary atonement, or biblical sex ethics. But the theme is the same: In order to make Christianity believable, certain doctrines must be abandoned.”

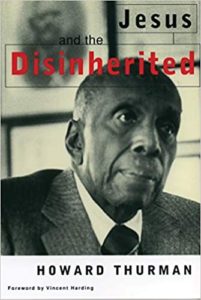

But the liberals I’ve known or read are not concerned with “rescuing” Christianity. For example, Howard Thurman was a 20th century Black early liberationist preacher, writer and professor whom TGC would consider a liberal. Out of more than 30 books, articles and lectures either by or about Thurman, the topic of atonement comes up just twice.

“The liberals I’ve known or read are not concerned with ‘rescuing’ Christianity.”

In “The Twofold Encounter” from The Inward Journey, Thurman says, “Man dare not face God on the Day of Atonement, seeking a right relation with him, unless man has already exhausted himself in redeeming all the broken relationships that he has with his fellows.”

Then in The Christian Minister and the Desegregation Decision, Thurman says, “Man emerges from his spiritual crisis deeply chastened, and a new sense of community without boundaries begins to make revolutionary demands upon his total life pattern. His task now becomes not only one of atonement as the catharsis for his guilt but also a new sense of social responsibility becomes a part of his Christian commitment.”

In those instances, Thurman’s atonement theology is mentioned as a theory toward the repairing of relationships in a social justice framework. He would have lined up much more with the moral example atonement theory of the 12th century’s Peter Abelard than with the satisfaction theory of Anselm that eventually would give birth to Calvin’s penal substitutionary atonement theory that TGC promotes as “the gospel.”

In those instances, Thurman’s atonement theology is mentioned as a theory toward the repairing of relationships in a social justice framework. He would have lined up much more with the moral example atonement theory of the 12th century’s Peter Abelard than with the satisfaction theory of Anselm that eventually would give birth to Calvin’s penal substitutionary atonement theory that TGC promotes as “the gospel.”

Additionally, Thurman was progressive in his sexual ethics, even writing his master’s thesis in 1926 about how prohibitions against pre-marital sex have been built on sexist, hierarchical theologies that oppress women — primarily the ancient and outdated belief that women are either the property of their fathers or their husbands.

In other words, according to TGC, Thurman would be considered a “liberal theologian.” So did Thurman ever say his goal was to rescue Christianity?

Quite the opposite.

Thurman said that “American Christianity has betrayed the religion of Jesus almost beyond redemption.” For Thurman, Christianity was not something to be rescued because Christianity had become an empirical hierarchy of the powerful and the ruling class and “seems impotent to deal radically, and therefore effectively, with the issues of discrimination and injustice on the basis of race, religion and national origin.”

“For Thurman, the goal of the religion of Jesus was a love ethic that would transform the entire ethical field of self, neighbor and enemy, where none experience separation and all converge in love.”

In Jesus and the Disinherited, Thurman distinguished between the empire of Christianity and the religion of Jesus by identifying the oppressed with Jesus in their struggle to survive separation through violence or the threat of violence under the empire of the privileged and the powerful — through an inner, radical change by way of the personal, love-driven religion of Jesus.

For Thurman, the goal of the religion of Jesus was a love ethic that would transform the entire ethical field of self, neighbor and enemy, where none experience separation and all converge in love.

Thus, his goal was not to “rescue Christianity by excising the elements that seem most offensive in that day,” but to liberate the oppressed by dismantling the abusive power dynamics of hierarchy and transforming self, neighbor and enemy with the love ethic of the religion of Jesus. He was not concerned with making Christianity “believable.” Christianity as doctrines to be believed is the theological lens of The Gospel Coalition. Thurman had an entirely different lens, the lens of following the love ethic of Jesus.

The definition of liberalism

Doriani then defines theological liberalism as “Bible interpretation unconstrained by orthodox creeds or doctrines.” His definition reveals conservative framework assumptions about interpretation that liberal theologians simply do not share.

One could infer from his definition of liberalism that theological conservatism would constrain biblical interpretation by orthodox creeds and doctrines. But whose creeds and whose doctrines? The Western church? The Eastern church? And which denomination?

“His definition reveals conservative framework assumptions about interpretation that liberal theologians simply do not share.”

In every theologically conservative culture I’ve been in, from the independent Baptist culture of my youth to the evangelical culture of TGC, the common assumption was that God revealed eternal, objective truth in the Bible that united Christians and that many began to deviate from. In the rare instance that we mentioned creeds, they were seen as moments to clarify what orthodox Christians already believed were true. Examining the power dynamics of the church councils never would have been a topic of consideration. And the possibility of Christian doctrine evolving over time and being worked out within culturally situated contexts and what the implications of that might be for us never really dawned on us.

The Gospel Coalition recently published an article that takes statements from early church fathers out of context and assumes modern definitions of terms in an attempt to promote the idea that penal substitutionary atonement was the position of the early church fathers, rather than the much later culturally situated development of Calvin building off and contrasting from the culturally situated satisfaction theology of Anselm.

In other words, these “orthodox creeds or doctrines” that TGC believes must constrain biblical interpretation developed over time in culturally situated contexts filled with power dynamics that may have affected their clarity of mind. Such a possibility is at least worth considering.

According to church historian Justo Gonzalez, the development of theological liberalism had something different in mind than unconstrained Bible interpretation. Because Darwin’s theory of evolution was so different than the creation stories of Genesis, Christians had to process whether to deny the mounting evidence of evolution or to reconsider biblical interpretation in light of our growing awareness of our cosmic story.

While recognizing that “a relatively small number of radicals — sometimes called modernists — for whom Christianity and the Bible were little more than another religion and one great book among many,” Gonzalez says, “most liberals were committed Christians whose very commitment drove them to respond to the intellectual challenges of their time in the hope of making the faith credible for modern people.”

That might sound similar to Doriani’s contention that the goal of the liberal theologian was to rescue Christianity and to make it believable by removing its offensive doctrines. But that’s not at all the case.

“Liberals were not simply removing offensive doctrines like eternal conscious torment but were reassessing how we understand reality in light of how different the story of evolution is from the story of Genesis.”

Liberals were not simply removing offensive doctrines like eternal conscious torment but were reassessing how we understand reality in light of how different the story of evolution is from the story of Genesis. As science continued to learn about the relationships within our minds and bodies, amongst ourselves and with the universe, and as archaeology continued to discover ancient documents and pottery that revealed the culturally situated conversations within even the Bible itself, the more liberal theologians continued to reassess biblical interpretation in light of those previously unknown revelations.

For one of my theology classes at Northern Baptist Theological Seminary, we defined theological liberalism not as “Bible interpretation unconstrained by orthodox creeds or doctrines,” but as, “a movement that interprets and reforms Christian teaching by taking into consideration modern knowledge, methods (including literary and historical criticism), science and ethics. It emphasizes the importance of reason and experience alongside doctrine.”

The ‘two types of liberals’

Out of his misrepresentations of the goal and definition of theological liberalism, Doriani attempts to categorize the “two types of liberals.”

He says, “The first, the hostile liberal, hates Christianity and wants to replace it with a better religion.” I am unsure who he is talking about here because he doesn’t give any modern examples. The most hostile criticisms today from liberal theologians that deny TGC’s “offensive doctrines” come from liberation theologians in the lines of Thurman or James Cone.

One such modern critic of TGC’s Christianity is Wendell Griffen. In a BNG article comparing white Christian America to the church at Sardis in Revelation 3, Griffen says, “My message to white Christian America is: ‘I know your works; you have a name of being alive, but you are dead.’ You are dead — meaning ineffective — concerning racial justice, including reparation for 400 years of bigotry, fraud, discrimination and hypocrisy. You are dead concerning love for immigrants. You are dead concerning love for women, girls and people who are LGBTQ. You are dead concerning love for people who do not worship God as you do. You are dead when it comes to concern for people who are not white and not privileged.”

While Griffen is hostile in his rhetoric, his hostility is not to the religion Jesus taught, but to the hierarchical power dynamics of white Christianity that abuses everyone who is not a white, heterosexual man.

“His hostility is not to the religion Jesus taught, but to the hierarchical power dynamics of white Christianity that abuses everyone who is not a white, heterosexual man.”

The second type of liberal, according to Doriani, “is more friendly. It hopes to rescue the faith and win its ‘cultured despisers.’” Doriani assumes, “Unfortunately, as friendly liberals attempt to save Christianity, they destroy it, for their first allegiance is to culture, not Scripture.”

Of course, to TGC’s readers, hearing that liberals’ first allegiance is to culture and not Scripture is going to sound horrifying. But Doriani is being dishonest about the amount of scientific, literary, historical, archeological, ethical and psychological evidence we have available to us today. He simply wraps all that up into the word “culture,” which any Bible-loving conservative evangelical reader can easily dismiss.

Based on my denial of penal substitutionary atonement, eternal conscious torment, inerrancy and TGC’s view of biblical sexual ethics, I would be considered a theological liberal. But I do not fit into either of their two categories for liberals. I’m not hostile to Christianity itself. I’m not trying to rescue the faith. And my first allegiance is not to culture. In fact, none of the theological liberals I mention in this article fit either of these two definitions. We have entirely different mindsets.

The role of experience in liberal and liberationist theologies

After summarizing what he believes to be the views of three liberal theologians born between 1768 to 1884, Doriani concludes that “all three men severed Christianity from doctrine in order to link it to experience.”

He goes on to describe the experience-driven nature of theological liberalism as “warm feelings,” as “adjusting doctrines that contemporary people just won’t accept,” as finding “aspects of Christian faith unpalatable,” and as following “the spirit of their age.”

“Where does this conservative evangelical aversion to empathy, compassion, friendliness and warm feelings come from?”

But where does this conservative evangelical aversion to empathy, compassion, friendliness and warm feelings come from? Since when does it make any sense to dismiss parents questioning their children potentially being kept alive to burn forever in a fiery furnace as simply having warm feelings? How did we come to think that if you don’t traumatize your 4-year-old with threats of eternal damnation that you’re simply unwilling to believe the unpalatable?

Wendell Griffen is correct. The heartless theological tradition of white Christianity that so easily dismisses the concerns, suffering, feelings and experiences of those who do not submit to the power dynamics and violent threats of their hierarchical theology is dead. It dismisses empathy, compassion and friendliness because its humanity is dead. And its humanity is dead because its theologies of justice through violence have numbed its heart to love.

In Lift Every Voice: Constructing Christian Theologies from the Underside, we read from 20 theologians about the commitment and construction of their theological methods, their theologies of God, eschatology, creating and governing grace, healing, liberating and sanctifying grace, Christology and the Scriptures. The theologies range from a wide variety of contexts. And each of them explains how their particular context has affected the lens through which they see themselves, their neighbors and God.

The depths of awareness these theologians have about how their experience on the underside of white theological power dynamics affects their theology is far beyond any levels of awareness I’ve ever experienced in conservative evangelicalism. Their depths of awareness are typical of what I’ve read from many theologians outside of retributive Christianity, because awareness tends to put us in touch with our humanity rather than cut us off from it.

So for Doriani to conclude his article by claiming that theological liberals stress authenticity “apparently without awareness that such ideals can be far more cultural than Scriptural” is beyond misunderstanding or misrepresentation. It’s abuse.

Rick Pidcock is a freelance writer based in South Carolina. He is a former Clemons Fellow with BNG and recently completed a master of arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five kids and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder. Follow his blog at www.rickpidcock.com

Related articles:

Six ways ‘American Gospel’ is small-minded and abusive | Analysis by Rick Pidcock

American Christianity in China also imports gender bias and Calvinism | Analysis by Rick Pidcock