Small and medium-size churches can navigate the challenges of postmodern culture and the COVID-19 pandemic by capitalizing on inherent strengths, embracing the neighborhoods that surround them and by adopting scaled-down practices from megachurches, one of the nation’s leading religion researchers said during a Dec. 9 webinar hosted by Baptist News Global.

And American congregations, big or small, must be open to new ways of cultivating leadership and of welcoming the ethnic, racial and sexual diversity long accepted by younger generations, said Scott Thumma, director of the Hartford Institute for Religion Research at Hartford International University. He was the guest on BNG’s Dec. 9 webinar with Executive Director Mark Wingfield.

“Diversity is increasing, and if congregations put their heads in the sand and turn a blind eye to this, they are going to remain the most segregated places on Sunday mornings,” Thumma said.

Scott Thumma

Thumma is a sociologist of religion and a veteran in the field of religion research with expertise in the megachurch movement, evangelicalism, LGBTQ faith and changes in American religious life, among others. He is a leader in the Faith Communities Today national research project and is the co-author of The Other 80 Percent, Beyond Megachurch Myths and Gay Religion.

During the hour-long Zoom and livestreamed session, Thumma also addressed questions about the pandemic’s lasting impact on congregational attendance and finances, how clergy have been challenged by major shifts in society and church, and the struggles of denominations to serve both the small and megachurches in their jurisdictions.

Big church, small church

He agreed with Wingfield’s assessment that American church life is divided between the haves and the have-nots in terms of attendance, money and other resources.

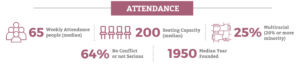

“It is stark in the religious landscape when only 10% of all the congregations in the country have the vast majority of people, and the median-size congregation is 65 attendees or less,” Thumma said. “And that group has only 15% of all people who go to churches.”

He added that 35,000 of the approximately 350,000 congregations in the United States account for 60% of overall church attendance. “That’s a really skewed graphic. There’s a vast number of small churches with almost no one in them and a relatively small percentage, and number, of congregations with the largest percent.”

This stark divide presents challenges for denominational officials — and denominations themselves — because the normal models of democratic representation skew toward the influence of the many small churches, which is not where the majority of churchgoers attend.

The pandemic

This tale of two kinds of churches also may be seen in response to the pandemic, Thumma said, noting that although deeper research into the pandemic’s effect on churches is forthcoming, it’s already obvious that congregations with more resources generally had an easier time of it than those with fewer resources.

“The congregations that went into the pandemic with ample resources and ready-made technology were able to weather it quite well as opposed a lot of the smaller congregations that struggled to figure out how to get on Zoom or do livestreaming,” he explained.

“The congregations that went into the pandemic with ample resources and ready-made technology were able to weather it quite well.”

But the picture isn’t an entirely gloomy one for smaller churches, he added. “There are some advantages to being small.” Those advantages include closer and often deeper relationships.

Church finances

Wingfield said he was stunned to learn that one of those advantages during the pandemic turned out to be financial. Again, data from Hartford and other sources show that churches that fare well financially during the pandemic have done very well and those that have fare poorly have been hit especially hard.

The upside of this phenomenon — the fact that most U.S. congregations have survived so far financially — may be explained by the fact that Americans “are incredibly generous in a crisis” and because disposable income increased for those still working but unable to dine out or take trips in 2020, Thumma said.

This is one place small and medium-size congregations may find an advantage over larger congregations, if those larger churches lose the personal touch of things like small groups, he indicated. “One of the things that comes across clearly in our Faith Communities Today research is that the larger the congregation gets, the less per capita giving it has, the less likely those people are to volunteer, to be fully engaged, because a large group doesn’t put the same kind of pressure on to be fully committed and to be fully involved as a small group.”

Part of the reason the current generation of megachurches has been so successful is by avoiding the construction of ever-larger buildings and instead creating small groups and satellite congregations in an effort to foster intimacy, “which in some sense replicates the small-church experience.”

Developing internal leadership

To survive and thrive, small congregations must recognize they already possess the qualities of intimacy and flexibility desired by big churches, he said. They can then seek to replicate the creativity in ministry that megachurches often exhibit.

“I think there is hope for revitalizing small churches and capitalizing on what they do well, which is create intimacy and also a significant level of commitment,” Thumma said.

That can be accomplished “if small churches could understand where their values and their gifts are, and then find ways to upscale by connecting with other small churches so that they could do significant interactions in the community.”

That can be accomplished “if small churches could understand where their values and their gifts are, and then find ways to upscale by connecting with other small churches so that they could do significant interactions in the community.”

And it is possible for small and medium-size churches to emulate some of the practices megachurches learned from from Disney, Walmart, shopping malls and other institutions, he explained. “There was a lot of borrowing in those early days. The megachurches didn’t invent all this stuff.”

As an example, Thumma suggested smaller congregations might also benefit from using multiple large screens in their sanctuaries to help worshipers feel more involved in worship. If congregations were more intentional about such practices “I’m sure they would thrive a good bit more.”

Megachurches also should be emulated in the way they develop leadership, Thumma explained. Large congregations have become known for cultivating leaders from within their ranks instead of routinely bringing in outside clergy, and also for not pigeon-holing candidates into one kind of ministry.

“What we see in a lot of megachurches is that they are not looking for people for specific roles, but for leadership qualities and potential” that can be used in various ministries, he said.

This has been especially helpful in creating ethnic diversity in congregations, Thumma said. Rather than trying to fill allotted places to create diversity, “megachurches find ways to identify natural leaders in the congregation and then create explicit pathways to leadership that cut across the different racial groups.”

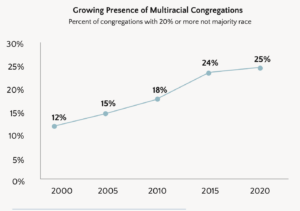

This is one of the drivers behind Hartford data that show that in a quarter of all congregations, at least 20% of members are not part of the dominant race of those fellowships and that 10% of congregations are so diverse that there is no majority racial or ethnic group.

LGBTQ trends

Two or three decades ago, Thumma documented the barriers to inclusion facing the LGBTQ community. And even though the majority of U.S. congregations are neither welcoming nor affirming of gay, lesbian and transgender members, the number of congregations that are now welcoming is notable.

Thumma said if someone had asked him 20 or 30 years ago what the landscape would be like today, he would not have predicted the sea change that has happened in American culture, politics and religious life.

“Part of the struggle we’re seeing is that the culture and the younger generations have far outpaced the vast majority of congregations and people and laws.”

“Part of the struggle we’re seeing is that the culture and the younger generations have far outpaced the vast majority of congregations and people and laws,” he said. “So, there is a disconnect there.”

Current research shows that “the vast majority” of Americans under age 35 support LGBTQ rights and inclusion, he said. “It will take time and generational change” for the rest of the church to reflect that trend, but the change is inevitable.

Is the clergy crisis real?

Prior to the pandemic, pastors faced daunting challenges of adapting to cultural and organizational change. The rapid adaptation required by COVID, mixed with the nation’s fraught political landscape, has escalated reports of clergy burnout and resignations.

Yet while the reports of a larger-than-usual number of clergy leaving their posts are true, that’s still descriptive of only a small percentage of U.S. clergy, Thumma said, echoing an earlier point he made about how some pastors and denominational officials and even church consultants are prone to generalize what they are seeing, even if their personal dataset is not the same as a national sample.

National research has confirmed the challenges ministers have faced from culture and the coronavirus, Thumma said. “Clergy have noticed for the past 20 years, and especially the last 10 years, that their old, tried-and-true methods don’t work so well as the world has changed around them. … Throw in in the pandemic, and that is a whole new component.”

But America’s clergy are far from being beaten, he added. Clergy were asked in a recent Hartford survey if 2020 was the hardest ministry year they had ever experienced. Two-thirds said it was.

“But when we asked them if they were considering leaving (ministry), 80% said they never thought that during the worst year of their ministry.”

“But when we asked them if they were considering leaving (ministry), 80% said they never thought that during the worst year of their ministry,” Thumma said. Only 37% confirmed that thought crossed their minds, and only 8% said they seriously considered quitting.

“I understand there is going to be some churn, and like every profession people are saying ‘I want to reconsider this.’ But I am not seeing more than 10%” seriously thinking of abandoning their callings, Thumma said.

But those who stay will have their work cut out for them, especially as the long-term effects of the pandemic on membership and attendance become more apparent, he quickly added. “It’s clear from the data that congregations are not back to where they were in 2019 in terms of attendance,” including some that are 20% to 40% below previous levels.

Still unknown is whether those who began attending church online during the pandemic will return to physical activities, and how congregations can more fully relate with those who don’t return.

The challenge is this, he said: “How are they going to connect with their virtual folks to make them truly members, not just spectators?”

Related articles:

Largest-ever U.S. congregational survey confirms what church consultants have been telling you

Most comprehensive study yet of COVID’s impact on churches finds uneven results