While research shows that many Black Christians prefer to attend racially diverse congregations, predominantly Black churches will continue to hold strong as racism surges across the nation, according to historian and author Jemar Tisby.

“More than half of people in all age groups still attend a Black church. There is an increasing trend, however, toward Black churchgoers, especially among the younger generations, choosing white and multiracial congregations as their faith communities,” Tisby writes in Black Perspectives, the official blog of the African American Intellectual History Society.

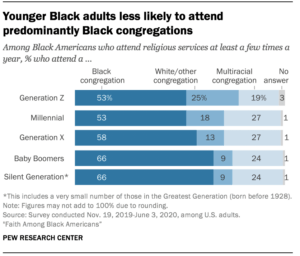

Tisby opens the February post, “Crossing the Ecclesiastical Color Line: Black Churchgoers in Multiracial Congregations,” with a summary of a 2021 Pew Research Center survey that found 60% of church-going Black Americans attend predominantly Black congregations, compared to 13% who attend white churches and 25% who worship in multiracial settings.

But it also captured a trend of young Black adults increasingly unlikely to attend predominantly Black churches. Pew reported that only 53% of Generation Z and Millennials, and 58% of Generation X Black Americans, say they are inclined to attend Black churches, contrasted with 66% of Boomers and older adults who do so.

But it also captured a trend of young Black adults increasingly unlikely to attend predominantly Black churches. Pew reported that only 53% of Generation Z and Millennials, and 58% of Generation X Black Americans, say they are inclined to attend Black churches, contrasted with 66% of Boomers and older adults who do so.

“The fact that half of all Black churchgoers still attend a predominantly Black church, juxtaposed with increasing numbers who attend white or multiracial congregations, calls into question the future of the Black church in reference to its past,” writes Tisby, author of The Color of Compromise: The Truth about the American Church’s Complicity in Racism.

“Upon closer examination, however, churches in the United States have never been uniformly segregated along racial lines. There has always been a degree of racial mixing in churches even as there is still much truth to the adage ‘11 o’clock on Sunday morning is the most segregated hour in America.’”

Tisby builds a historical case to demonstrate why younger adults trending away from predominantly Black congregations is not a predictor for the future health of the church.

“In the years prior to the Civil War, some racial integration in Christian churches occurred, but mainly as a way for white leaders to control the actions and religious life of Black people,” he writes, adding that Sunday morning became the nation’s most segregated hour only after the end of the Civil War and emancipation.

“Yet even under the same roof, Black people were treated as second-class citizens in the household of God. In one example, Anglican leaders excised portions and even entire books of the Bible to form an edited ‘Slave Bible’ that emphasized obedience to earthly masters and hard-work messages befitting the moral uplift and diligence of people who were considered property and enslaved for life.”

Jemar Tisby

Consequently, many Black Christians were eager to launch their own churches after years of discrimination in white congregations and denominations, Tisby writes. “As soon as they could feasibly extricate themselves from predominantly white congregations, they did so with speed and creativity. Several historically Black denominations still in operation today trace their origins to the years following emancipation including the Christian (formerly Colored) Methodist Episcopal Church (1870), the National Baptist Convention (1895), and the Church of God in Christ (1907).”

At the same time, other Black Americans continued to seek worship in interracial settings. “In 1906, William Seymour, a Black preacher and evangelist, led a religious revival that witnesses said included speaking in tongues, miraculous healings, and holy trances. At first, these meetings, which lasted for months, included people of various races. … Despite these interracial beginnings, however, Pentecostals would eventually split along racial lines.”

But these movements often were shaken as Black worshipers realized their white counterparts were interested not in true interracial harmony, but in their own racial comfort and dominance. Tisby writes that is a reality that has continued to plague many racially diverse congregations.

“While the number of multiracial congregations has tripled over the course of 20 years, interracial worship among Black and white churchgoers remains a tenuous proposition. Sociologist Korie L. Edwards of Ohio State University records in her book, The Elusive Dream, that for white people at these churches their sense of connectedness to the church was fragile and dependent upon the church’s affirmation of whiteness.’ When white people feel their priorities and preferences being challenged, they often leave multiracial church settings.”

Tisby cites a 2018 New York Times piece by Campbell Robertson detailing Black abandonment of white churches due to the racial insensitivity of Trumpism. “It has been a scattered exodus — a few here, a few there — and mostly quiet, more in fatigue and heartbreak than outrage,” that article states.

If nothing else, the trend bodes well for the future of the Black church as African American hopes of faith-based racial reconciliation are frustrated, Tisby adds. “The departure of Black Christians from white religious spaces indicates that even in interracial settings, people of color can face insurmountable obstacles to integration.”

Related articles:

Barna: Racism a reality even in multiracial churches

The ‘MAGA faction’ could be a hindrance for multiracial congregations

More churches defined as racially diverse but that doesn’t lead to racial justice work