On March 29 in the year of our Lord(?) 2023, hundreds of young people, many of junior and senior high school age, descended on the Tennessee state house in Nashville to demand government action to reduce the threat of school shootings. The protests began only three days after six human beings were murdered by a shooter using a semiautomatic weapon at the Covenant (Presbyterian) School in Nashville. Three of the victims were only 9 years old.

The Arkansas Democrat Gazette reported that protesters, urging lawmakers to ban assault weapons like those used in the school shooting, chanted:

- “What do we want? Gun control. When do we want it? Now!”

- “Do your job! Do your job!”

- A young woman in a red bandanna with a pink whistle held a sign that said, “I turn 18 today. Hallie, William and Evelyn never will,” in reference to the three 9-year-olds killed.

- Young children, teenagers and parents stood in a light drizzle and 53-degree temperatures. They held an extended, bloodcurdling scream for more than three minutes, then chanted “14 minutes. 14 minutes. Six lives. Six lives.”

Bill Leonard

When legislative supermajority Republicans became more obsessed with the children’s protests than the Nashville shooting itself, three Democrats — Justin Jones, Gloria Johnson and Justin Pearson — went to the well of the House, lending their voices to those of the gallery-packed dissenters. The three insisted their brief, but dramatic, action was necessary after a supermajority of the peoples’ representatives refused to discuss the possibility of outlawing assault weapons.

Speaker of the House Cameron Sexton condemned their response, declaring it was “at least equivalent, maybe worse, depending on how you look at it” to the January 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. Sexton led the legislature in charging the “Tennessee Three” with “disorderly behavior,” “knowingly and intentionally” bringing “disorder and dishonor to the House of Representatives through their individual and collective actions.”

On Maundy Thursday, the supermajority voted to expel the two Black representatives, Pearson and Jones, thereby adding a racial component to the controversy. Johnson, who is white, was spared expulsion by one vote. (As of yesterday, both Pearson and Jones are being sent back to fill their own vacancies, by vote of responsible bodies in Nashville and Memphis.)

When asked why she survived dismissal, Johnson replied, “It might have to do with the color of our skin.” Elie Mystal, Harvard law graduate and justice correspondent for The Nation, observed: “Tennessee is giving a more abject lesson in Critical Race Theory than any AP History course possibly could,” thereby illustrating the continued presence of systemic racism in the American Republic.

Does nothing change? Watching the exile of two Black members of the Tennessee House of Representatives on Maundy Thursday 2023, I couldn’t help thinking of 1635, the year in which the Massachusetts General Court expelled Roger Williams, “one of the elders of the church of Salem,” for “having broached & divulged divers new & dangerous opinions, against the magistrates and churches here.” The governor and “two of the magistrates” were called upon to send Williams “to some place out of this jurisdiction, not to return any more without license from the court.”

The charges against Williams included:

- “That we have not our Land by Patent from the King, but that the Natives are the true owners of it, and that we ought to repent of such a receiving of it by Patent.” Race was an issue in 1635 Massachusetts as it is in 2023 Tennessee.

- “That it is not lawful to call a wicked person to Swear, to Pray, as being actions of God’s worship.” The oath was central to colonial society, yet Williams insisted that unbelievers should not be compelled to swear to a God in whom they had no belief.

- “That it is not lawful to hear any of the Ministers of the Parish Assemblies in England.” Williams was a Puritan Separatist who believed the Anglican Church was not a true Christian communion.

- “That the Civil Magistrates power extends only to the Bodies and Goods, and outward state of (citizens),” not to matters of souls and salvation. Religious liberty was born in such beliefs. For Roger Williams, there were no “Christian” nations, only Christian people, bound to Christ not by citizenship but by faith.

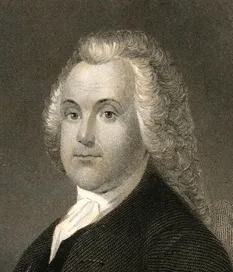

Roger Williams

In As to Roger Williams (1876), Congregational minister and historian Henry M. Dexter wrote that Williams’ “exclusion from the colony took place for reasons purely political, and having no relation to his views upon toleration, or upon any subject other than those which, in their bearing upon the common rights of property, upon the sanctions of the oath, and upon due subordination to the powers that be in the state, made him a subverter of the very foundations of the government.”

Does any of this 1635 case sound familiar in 2023?

Like the political supermajority in 17th century Boston, a supermajority in 21st century Tennessee determined to exile dissenters whose protests threatened not government, but governmental control.

Bill Moyers has written: “American dissent is older than the nation itself. Some of the first settlers were of course religious dissenters from England — referred to at the time with a capital ‘D.’ However, suppression of dissent has just as long a history — one need look no further than the mandatory church attendance laws put into practice by those very same early settlers.”

In Dissent in American Religion, historian Edwin Scott Gaustad laid out the imperative of dissent, writing, “Should a society (whether church or state) actually succeed … in suffocating all contrary opinion, then its own vital juices no longer flow and the shadow of death begins to fall across it.”

Gaustad acknowledged dissent can be “irritating, unnerving, pigheaded, noisy and brash. It can also be wrong.” Yet, citing Reinhold Niebuhr, he concluded that “consent makes democracy possible, dissent makes democracy meaningful.” He added: “It may also be a manifestation of the unfettered human spirit.”

“The Tennessee Legislature’s supermajority intends to ignore any hint of firearm legislation save training teachers to shoot to kill.”

This pathetic legislative distraction by the Republican supermajority must not distract from the real issue — the massacre of six individuals, three adults and three children, in a private Christian school in the heart of the American South. The Tennessee Legislature’s supermajority intends to ignore any hint of firearm legislation save training teachers to shoot to kill. While they and other state legislatures prefer to protect Americans from drag queens, Critical Race Theory and “dangerous” books, mass shootings continue unabated, not only in schools, but throughout American society.

No place is truly safe. On Easter Monday, five people were gunned down in a Louisville, Ky., bank by a 28-year-old bank employee. One of the dead was husband to a woman I have known for half a century.

In exile, Roger Williams bought land from the Narragansetts and established Providence in the Rhode Island colony. Of Providence, he wrote: “I desired it might be for a shelter for persons distressed by conscience. I communicated my said purchase unto loving friends, who desired to take shelter here with me.”

In America 2023, shelters for safety, let alone conscience, are increasingly illusory. The “extended, blood curdling screams” of American children know no end.

Bill Leonard is founding dean and the James and Marilyn Dunn professor of Baptist studies and church history emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, N.C. He is the author or editor of 25 books. A native Texan, he lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Candyce, and their daughter, Stephanie.

Related articles:

Tennessee legislators turn back the clock to Jim Crow time | Opinion by Rodney Kennedy

Hypocrisy | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

Tennessee representative who proposed execution by ‘hanging by a tree’ needs a history lesson | Opinion by Rodney Kennedy