Dedicating highways, schools, monuments and a national holiday to Martin Luther King Jr. often obscures his status as a radical bent on revolutionizing American race relations and faith, according to author and King scholar Lewis Brogdon.

Lewis Brogdon speaks to a BNG event in Loulisville, Ky., Sept. 7.

“Those are great things, and I don’t want to minimize the importance of naming roads after Dr. King or having his monument in Washington, D.C. But the lack of depth and complexity is the issue that I’m getting at. Most Americans have this simplistic understanding of Dr. King,” he said during a dinner hosted by Baptist News Global at Crescent Hill Baptist Church in Louisville, Ky., Sept. 7.

Brogdon serves as associate professor of preaching and Black church studies at the Baptist Seminary of Kentucky, where he also serves as executive director of the Institute for Black Church Studies.

Excerpts from King’s speeches and sermons have been reduced to platitudes Americans love to quote in speeches and in social media posts while ignoring the contributions and controversies he inspired as a radical until his death in 1968, Brogdon said. “How did Dr. King die? He did not die of old age. He was assassinated. Who wants to assassinate someone everyone loves? It doesn’t fit.”

Brogdon said his address, “The Radical Martin Luther King Jr. — Beyond the Caricature,” was designed to unpack the racial, religious and political context of King’s work, including actions that led to passage of Civil Rights acts banning discrimination in voting and housing based on race.

“Our understanding of what he stood for is laughable.”

“One of the most amusing and frustrating aspects of my work is to hear people’s very surface and shallow opinions and understandings about King,” the professor said. “You would be very hard-pressed to find another American in our history who has had the impact he has had, yet our understanding of what he stood for is laughable.”

The problem begins with the caricature of King as little more than a dreamer based on his “I Have a Dream” speech at the 1963 March on Washington. “When you think about Dr. King, most Americans are going to say, ‘Oh, Dr. King had a dream. He was a dreamer. He had a dream of a better America.’”

Martin Luther King Jr. talks with Southern Seminary Professor of Christian Ethics Henlee Barnette April 19, 1961, the day King spoke in Southern Seminary’s chapel and in Barnett’s Christian ethics class.

But that vision of King is simplistic, Brogdon declared. “Did you know that a few months after Dr. King talked about his dream, he told America his dream had become a nightmare? It’s interesting that we have this idea of King’s dream when, before he even died, America killed his dream.”

Overlooking King as an intellectual maintains the caricature of him even though he earned a doctorate from Boston University and crafted the vision and strategies that gave rise to the Civil Rights movement, Brogdon said. “You would think someone who leads a movement that literally changes the world, that his ideas would be studied, that every college and every university would teach his ideas. You would think his ideas would be taken seriously and studied in Christian colleges.”

But Baptist Seminary of Kentucky is one of only a few academic institutions that offer entire courses about King’s legacy and beliefs.

He attributed this lack of academic inquiry to a more pervasive form of racism.

“It is hard for any Black leader to get that kind of respect in the U.S.,” he said. “America has a problem with Black intellectualism. We saw that when (Barack) Obama was president, and he and Michelle (Obama) were Ivy League educated and Barack was the editor of the Harvard Law Review. Before his presidency, people said it’s great to give minorities a chance but that they needed to be more intelligent to do the job. And you want to know what a lot of people’s criticism of Barack was? ‘Well, he’s too intellectual.’”

“America has a problem with Black intellectualism.”

King also was too radical for many people’s tastes, especially after denouncing the Vietnam War in 1967. Brogdon cited Cornel West’s book, The Radical King which shows King’s disapproval ratings at that time rose to 72% among whites and 55% among Blacks.

“Most Blacks were against Martin as well. They started a new Baptist denomination (Progressive National Baptist Convention) because King got kicked out of a very, very conservative Black Baptist denomination (National Baptist Convention). Powerful nations and unjust systems hate leaders that expose and challenge the core of who we are.”

Brogdon explained that many Black pastors and churches tended to be conservative on Civil Rights issues to avoid stoking white anger and backlash, an approach historically promoted by Booker T. Washington. “What happened is that the masses of Black leaders adopted this accommodationist philosophy of ‘keep your head down. I know things aren’t right in the world, but you know the world’s going to hell anyway. You just get your ticket to heaven.’ That’s what they preached.”

But King was formed in the tradition of resistance embodied in slave spirituals and by activist W.E.B. DuBois, who called for civil action to oppose racism.

Resistance was at the core of King’s Civil Rights work, Brogdon said. “God called Dr. King to this work in his kitchen in the middle of the night after he got another threatening phone call saying someone was going to come over there and bomb his house and kill his wife and his children. Spirituality was a deep resource for King as he took up this work.”

Americans have diluted those and other facts about King in order to escape the uncomfortable lessons they contain, Brogdon suggested. “Does America have the capacity to hear the radical King? Must we sanitize him in order to avoid his challenge?”

Restoring King’s true memory begins with understanding the context of the 1950s and 1960s, he said. “King was dealing with the residuals and the legacy of centuries of slavery. For most of our history, our people were enslaved in this country and had no legal protections. Thousands of African Americans were being lynched. It was like going to a ball game. And this was going on for decades.”

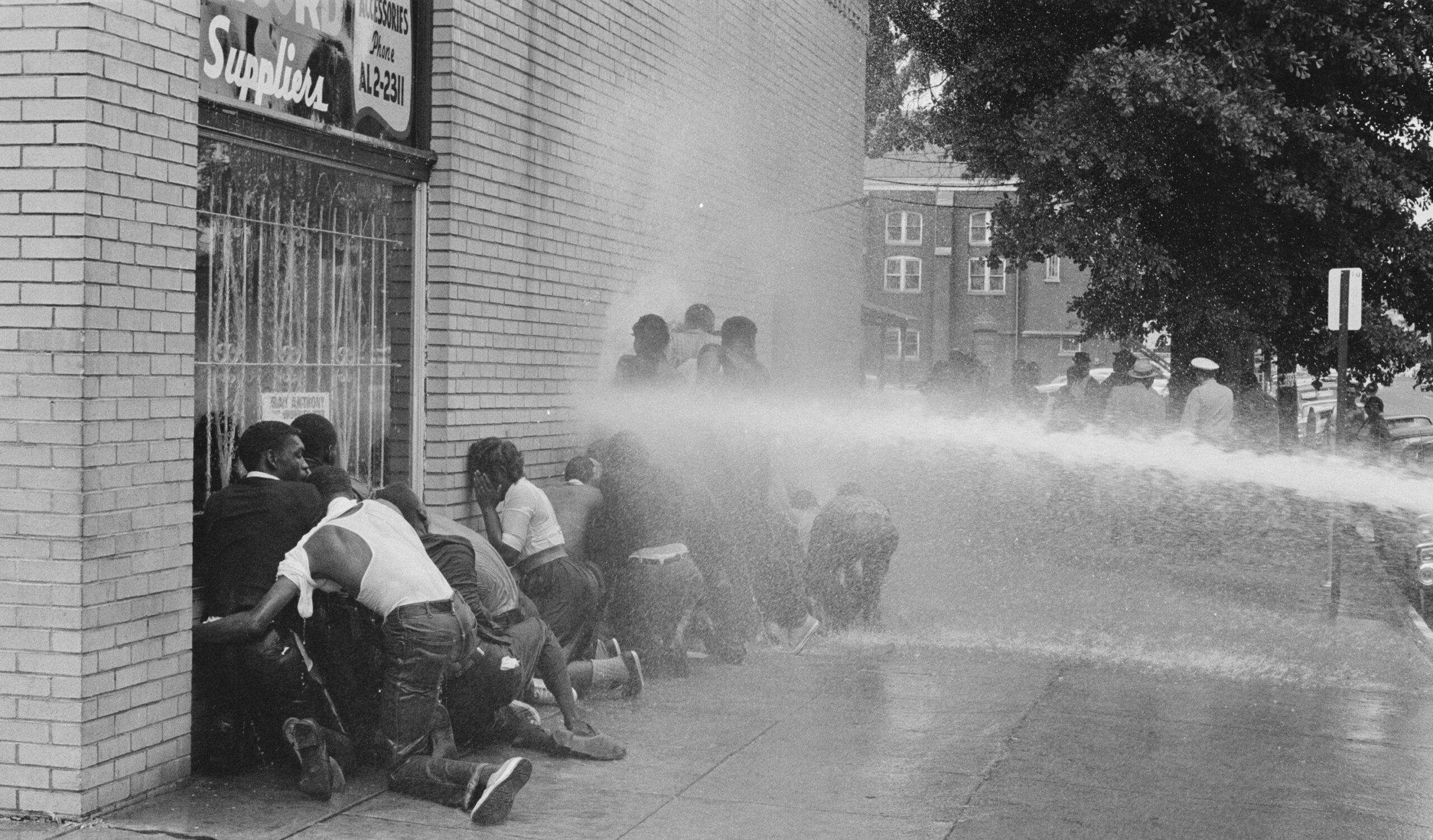

Firefighters use fire hoses to subdue protestors during the Birmingham Campaign in Birmingham, Ala., May 1963. The movement, which called for the integration of African Americans in schools, was organized by Fred Shuttlesworth. (Photo by Frank Rockstroh/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

This also was a time when huge social upheavals were generating rhetorical, political and violent backlash to the movement, Brogdon said. “There was widespread resistance. They were putting fire hoses to children, turning dogs on children, bombing a church in which four young Black girls were murdered. And on April 4, 1968, Dr. King was shot and killed. He didn’t die of old age.”

King’s philosophy of nonviolent direct action also needs to be understood to revive his full memory, Brogdon said. “King believed in resisting, but there was a way to resist. He was very principled about this. He got this philosophy from (Mahatma) Gandhi and then he appropriated Christian teaching to this philosophy. He stressed the importance of being rooted and grounded in love if you are going to do some of this work.”

King also pushed back against Christians who did not take sides in the struggle — a phenomenon also seen in the aftermath of the police killings of George Floyd and other Black Americans during and since the pandemic, Brogdon said.

“He taught that God calls us to take sides, to speak truth to power.”

“In 2020, you saw churches that were willing to stand up and say something, and then you saw the immense pressure on churches to not get involved. That’s the same religion that was saying don’t talk about slavery, don’t talk about the system of segregation. Just pray about it. People are being incarcerated and murdered by police officers. We’re not supposed to talk about that. King pushes back against a religion that’s OK with that. He taught that God calls us to take sides, to speak truth to power.”

That power is as daunting today as it was in King’s time, Brogdon said. “In 2020 our (white) sisters and brothers wanted to listen. By 2021, they were tired of listening and they didn’t want us to talk about it anymore. And they started the whole attack with Critical Race Theory. Now it’s on to diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging, dismantling programs, eliminating positions, removing funding. It’s hard to make progress because there’s so much fatigue in the white community.”

A little-remembered fact about King’s ministry is that it was increasingly focused on the issue of economic inequality, the professor said. “King was a different kind of religious leader. He was trying to make a difference in the material conditions of the nation. He wasn’t just concerned about a form of religion or about us going to church all the time. He was a leader who was actually engaging with politicians at the local, the state and the federal levels. It was about advocacy and bringing material change.”

Few Americans know that King once proposed creation of a U.S. cabinet-level position to oversee matters of racial justice, and that he had a lineup of quotations few have ever seen. They include, “This is a sick society” and “Most Americans are unconscious racists” and “If our nation can spend $35 billion a year to fight an unjust, evil war in Vietnam, and $20 billion to put a man on the moon, it can spend billions of dollars to put God’s children on their own two feet right here on earth.”

Related articles:

More than a dream: The undiluted legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. | Analysis by Joel Bowman

Photo essay: 60th anniversary of the March on Washington

60 years later, only our action can keep the dream alive | Opinion by Todd Thomason

5 ministers reflect on the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington

MLK’s civil rights work was an outgrowth of his Baptist tradition, author explains