Of late, as regular readers know, I’ve been reflecting on how conservative American Christianity has chased political and temporal power to the great detriment of its mission and our common witness, how the Church, instead of being light and leaven, has been and still often is part of the system of repression.

I’ve talked with Robert P. Jones for BNG about his new book The Hidden Roots of White Supremacy. I’ve interviewed Andrew Whitehead here on his study of evangelical Christianity, American Idolatry. I read Tim Alberta’s deeply-sourced study, The Kingdom, The Power, and the Glory and prepped an interview with him about his — our — experience in the conservative Christian tradition.

I’ve spoken and am still speaking publicly and to the media about James Baldwin’s lessons for the American Church and our American experiment in this, the 100th anniversary of his birth. And in the fall, I had the experience of hosting Anthony Reddie, England’s preeminent liberation theologian, at Baylor University, of listening to him speak, talking with him onstage and leaning into hours of conversations about life, love, faith and justice as we drove across Texas.

I don’t believe in accidents. My mother has a sentence I often call to mind when I’m thinking about discernment: “Look for the open doors.”

I don’t believe in accidents. My mother has a sentence I often call to mind when I’m thinking about discernment: “Look for the open doors.”

I’ve encountered open doors for the past seven years as I’ve entered into the good hard work of writing and talking about racial justice, as deep friendships with Black pastors and theologians have shaped and supported that work, as external funding threw that door further open than my own words ever could.

Devoted as I am and will ever be to racial reconciliation, in this election year, a door seems to have opened off that vestibule, a door into work that faithfully engages race, justice, political power and the good news of Jesus Christ.

PRRI polling indicates conservative American Christians — the evangelicals who support Donald Trump, who rail against the rights of women, people of color and LGTBQ persons, and who believe it may be necessary to take up arms to preserve “their” America, an America controlled by white straight Protestant males — have a distorted and dangerous view of reality. They see Christianity and conservative American values as under siege. They imagine white conservatives like themselves are the ones in need of protection, even as the truly dispossessed among us suffer indignities and inequities that I will never know while walking around in my straight white Christian skin.

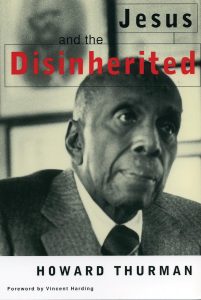

As Howard Thurman notes in Jesus and the Disinherited, when a people prioritizes security and status instead of surrender and sacrifice, their religion will operate against the marginalized instead of on their behalf, will become part of “a ruthless use of power applied to weak and defenseless people.” One of Tim Alberta’s subjects said this current form of American Christianity dishonors Jesus and prompted him to call for a truer, more faithful American Christianity.

As Howard Thurman notes in Jesus and the Disinherited, when a people prioritizes security and status instead of surrender and sacrifice, their religion will operate against the marginalized instead of on their behalf, will become part of “a ruthless use of power applied to weak and defenseless people.” One of Tim Alberta’s subjects said this current form of American Christianity dishonors Jesus and prompted him to call for a truer, more faithful American Christianity.

What that truer, more faithful faith and practice is or could be is the conversation I want to bring into this space this year.

One of my tasks as a theologian is to try to find where and how God is operating in a given moment, to look for the open door, theologically speaking. This I have discerned: God’s liberating presence cannot be located inside white Christian nationalism, within any political movement that demeans, hates and terrorizes its opponents, or alongside any version of the Church that marginalizes or abuses any of God’s children.

As a theologian, I read, I study and I pray for wisdom, and when I believe Spirit has gifted something others might need to hear, I offer it. That personal work and reflection matters.

We discern in community. We need each other to limn our areas of blindness, to encourage us to stand strong in the faith and to challenge us to live into the gospel message of love and courage, that faith and practice characterized by what Dr. King called “dangerous unselfishness.”

But I also know my work as a theologian is shaped by partnership and conversation. Our participation in the Body of Christ encompasses more than worship and communal prayer, powerful as those are. We discern in community. We need each other to limn our areas of blindness, to encourage us to stand strong in the faith and to challenge us to live into the gospel message of love and courage, that faith and practice characterized by what Dr. King called “dangerous unselfishness.”

In my collaboration with Baptist pastors like Hulitt Gloer, George Mason and Ralph Douglas West, in my friendship and apprenticeship in the theologies of the oppressed with Kelly Brown Douglas, Anthony Reddie and Reggie Williams, in the witness of so many churches and faith communities who love and serve and welcome, I have found insights and relationships that point toward open doors.

This year, I’m going to convene conversations here that can help us consider what it means to be light and leaven, talk with folks about the open doors through which they are stepping, and ask them to challenge us to be the Body of Christ in this year when so much seems to be on the line.

I plan to begin by talking with Jemar Tisby and Russell Moore, and from there, to build out this discussion with more inspiration, more challenge, more thoughtful voices every week or two.

I am grateful for the blessing of my editor, Mark Wingfield, for the many suggestions I’ve received, for friends old and new willing to talk with me about their work in their communities of faith.

And I want to close with this theological affirmation: In my last column I wrote that I was terrified about the damage done to the Church’s witness and our political system by bad Christianity, by the high stakes for this Church I serve and this nation I love.

I wrote that I was so cognizant of the manifold dangers that 2023 might present.

I also know who holds the future, and unlike the former president, I will never suggest that the Bible, the Church, or the Most Holy One of Israel could be damaged by any politician or political movement, now or ever.

But Howard Thurman writes in Jesus of the Disinherited that even knowing and believing in our ultimate future, we who follow the way of Christ must reach out now, in this time, in love, a love that is “a discipline, a method, a technique, as over against some form of wishful thinking or simple desiring.”

As I often say on social media, now is the time to love hard.

I look forward to the conversations that will take place here and hope they will offer us the insight and courage that will help us love hard this year. Please join us for this hard and holy work.

Greg Garrett teaches creative writing, film, literature and theology classes at Baylor University. He is the author of two dozen books of fiction, nonfiction, memoir and translation, including the critically acclaimed novels Free Bird, Cycling, Shame and The Prodigal. His latest novel is Bastille Day. He is one of America’s leading voices on religion and culture. Two of his recent nonfiction books are In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

Related articles:

Journalist’s book explores ‘crack-up of the American evangelical church’

Are young voters switching to Trump over Israel’s war?

‘Vermin’: Trump crosses fully into Nazi territory