Last week, I welcomed Robert P. Jones back to Baylor University for a conversation about race, religion, James Baldwin and American democracy. Jones was a keynote speaker for our first Baylor conference on racism in the church in 2021, and is a renowned writer, the founder of Public Religion Research Institute, an essential resource on race, religion and politics, and a cherished friend and colleague in the work of racial repair.

Jones’ new book The Hidden Roots of White Supremacy: And the Path to a Shared American Future premiered on the New York Times bestseller list. It was a joy last week to discuss his book in front of a packed room at the Baylor University Libraries, and it’s a joy now to share this new interview with you and to anticipate further conversations and collaboration with him and PRRI.

Greg Garrett in dialogue with Robert P. Jones (Screencap)

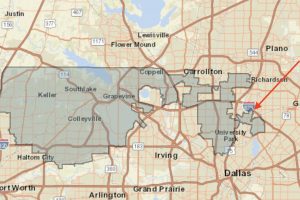

Greg Garrett: After two essential and extremely well-received books (The End of White Christian America, 2016, and White Too Long, 2020), you’ve turned in The Hidden Roots of White Supremacy to three particular locations — Mississippi, Minnesota and Oklahoma — where you dig into America’s racist history. What does this book offer readers wanting new ways to think about our past and present?

Robert P. Jones: The learning edge for me in this book was telling a more complete story about the European arrival and colonization of the United States and the Americas. This quest involved connecting the histories of European engagement with both Africans and indigenous peoples and understanding how European Christianity shaped those encounters.

I also wanted to tell that history very concretely, to see the way it played out in specific places in the country. That journey revealed the connections between Emmett Till and the Spanish conquistador Hernando De Soto in the Mississippi Delta, between the lynching of three Black circus workers in Duluth and the mass execution of 38 Dakota men in Mankato, and between the murder of 300 African Americans during the burning of Black Wall Street in Tulsa and the Trail of Tears.

GG: You suggest that instead of arguing about whether America’s history begins in 1619 or 1776, we need to recognize how our history actually goes back thousands of years. What does thinking in this way allow us to see about who and what America is? And how does including both indigenous and Black stories reshape some of the ways we think about race and privilege?

“Genesis stories … emerge out of the need to make sense of, and to justify, the shape of the present.”

RJ: First, I want to emphasize that these are not trivial arguments. Genesis stories are never accidental. They emerge out of the need to make sense of, and to justify, the shape of the present. Whatever is in that initial frame, the “in the beginning,” has to be part of the narrative of the present.

So if we begin with an image of a group of white men dressed in colonial finery gathered around a table in 1776 Philadelphia to sign the Declaration of Independence, that lays the foundation for a simplistic narrative, laced with positive virtues: freedom, independence, equality. If we start with an image of a single ship containing Africans who are destined for servitude and enslavement in the early British colonies crossing a menacing ocean in 1619, that sets the stage for a much more complex and challenging national narrative. But even that more complete narrative doesn’t account for more than a century of prior European contact with indigenous peoples that was marked by violence and deception.

By widening the aperture to at least 1493 and seeing these histories together, we get a more honest understanding of the country and the ways European Christians have conducted ourselves toward these groups.

By widening the aperture to at least 1493 and seeing these histories together, we get a more honest understanding of the country and the ways European Christians have conducted ourselves toward these groups.

GG: James Baldwin says progress is impossible in America unless we tell the truth about our history, but you and I know that often the worst events remain hidden. What are some of the things you write about that have been largely wiped from our history? Why are so many states insisting a white-washed or incomplete version of American history be taught to our kids?

RJ: It’s striking to me that each of the three events of white racial violence I cover in the book — the murder of Emmett Till in the Mississippi Delta, the killing of over 300 African Americans and the burning of the entire Greenwood neighborhood in Tulsa, and the lynching of three Black men in Duluth — remained largely forgotten and covered up until about two decades ago. And these places are not unique.

“I could have easily written a similar chapter for every state in the nation.”

I could have easily written a similar chapter for every state in the nation, narrating a history of genocide and forced removal of Native Americans, enslavement of and violence against African Americans, followed by overt attempts to cover up the violence and a sustained willful amnesia.

Today, the progress we are seeing in uncovering these hidden histories has precipitated the backlash that is manifesting itself in book bans and disingenuous denouncements of “Critical Race Theory” that are, at their core, just defensive attempts to suppress attempts to tell the whole truth about how we got here.

GG: You argue that democracy and Christianity have failed to defeat white supremacy in America, but you do write about some possible remedies. How can we go about repairing the damage done to our country, our religious institutions and ourselves? How can we, as Baldwin says, “do better”?

RJ: One of the most inspiring things I learned from the folks working on the ground in Mississippi, Oklahoma and Minnesota was that everyday people working with few resources can come together to tell the truth and make a difference.

To give just one example, a group consisting of descendants of enslaved people and sharecroppers joined hands with descendants of enslavers to tell the story of Emmett Till in Tallahatchie, Miss. Their work, over a period of two decades, resulted in the establishment of the Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley National Monument, announced earlier this year by President Joe Biden.

“I don’t need white Christians to be smarter. I need them to be better.”

I come back often to Baldwin’s simple wisdom: that despite everything, and even despite ourselves, we can do and be better. I’m reminded of something similar Rev. Jim Bear Jacobs, a member of the Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican Nation and director of racial justice for the Minnesota Council of Churches, said to a group of white evangelicals who had joined us for a tour of indigenous sites around Minneapolis. When a woman asked him what he hoped groups of white Christians like them would take away from the experience, Rev. Jacobs responded simply: “I don’t need white Christians to be smarter. I need them to be better.”

GG: Who are some of the individuals who most inspired you as you researched and wrote The Hidden Roots of White Supremacy? What did you learn from them about white supremacy that you knew you needed to get into the book?

RJ: As you know, James Baldwin’s criticism of white America, and particularly white Christians, haunted me as I wrote my last book, White Too Long, which took its title from his writing. In my new book, the words of indigenous scholar Vine Deloria Jr. (Lakota, Standing Rock Sioux) have also stayed with me.

In 1972, for example, Deloria penned “An Open Letter to the Heads of the Christian Churches in America,” calling on Christian clergy and denominational leaders to begin “an honest inquiry by yourselves into the nature of your situation.” The heart of Deloria’s critique was that white Christians had fabricated a dishonest history that denied the impact of the Christian Doctrine of Discovery on both indigenous people and themselves.

Baldwin and Deloria alike saw that the powerful myth of white Christian innocence fueled a false consciousness for white Americans that continued to harm Black and indigenous people. Both of them, along with other witnesses of color, were largely dismissed in their day by the white Christian establishment and by white Christians in the pews. One way of understanding each of my last two books is to read them as one white Christian’s attempt to wrestle with these faithful indictments as honestly as possible.

Greg Garrett teaches creative writing, film, literature and theology classes at Baylor University. He is the author of two dozen books of fiction, nonfiction, memoir and translation, including the critically acclaimed novels Free Bird, Cycling, Shame and The Prodigal. His latest novel is Bastille Day. He is one of America’s leading voices on religion and culture. Two of his recent nonfiction books are In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

Related articles in this series:

American idols: Andrew Whitehead on American faith and Christian nationalism

White reflections on racism: An interview with Frederick Allen

Broken covenant: An interview with Vann Newkirk II about ‘Holy Week,’ MLK and white supremacy

‘In a pluralistic democracy’: An interview with Jennifer Rubin

‘What can we forgive?’: An interview with Matthew Ichihashi Potts on Forgiveness

A conversation with Anthony Reddie about the importance of James Cone