Bishop elections in The United Methodist Church are typically the kind of institutional politics only those with a major stake in the organization care about. This year, however, delegates to the UMC’s jurisdictional conferences coming July 10-12 face a new set of challenges that will affect UMC workings down to the smallest congregation.

This year, the task of electing bishops bodes to be tougher and more complex than it has been since 1968, when the newly formed United Methodist Church abolished the racially segregated Central Jurisdiction and integrated Black clergy into the predominantly white UMC.

Bishops are considered the UMC’s top executives responsible for the UMC’s “spiritual and temporal” care. Those duties include presiding at church functions, preaching, teaching and fostering ecumenical relationships, among others.

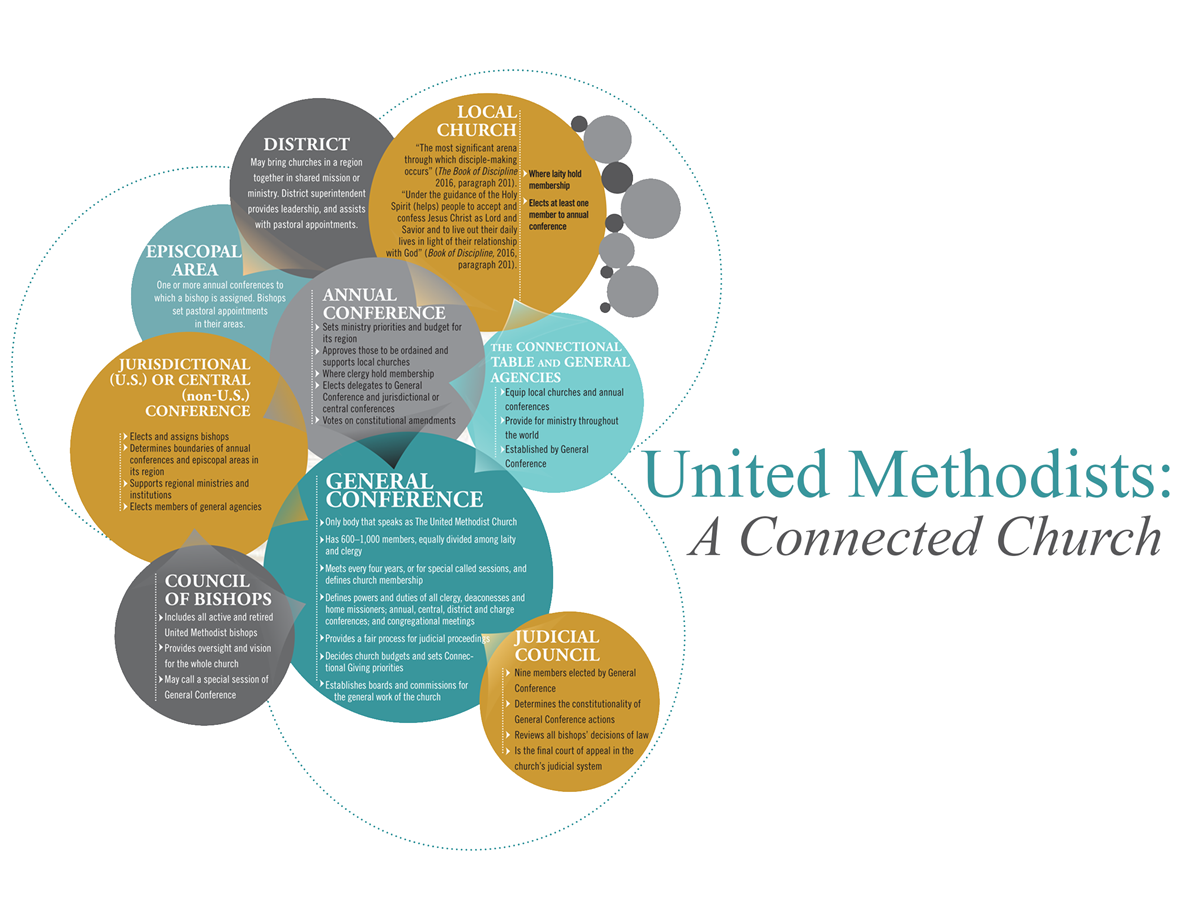

Bishops’ primary administrative function is to assign clergy according to the conference’s missional needs. This process of appointing clergy, rather than churches calling their own pastors, forms a major aspect of the UMC’s “connectional” system.

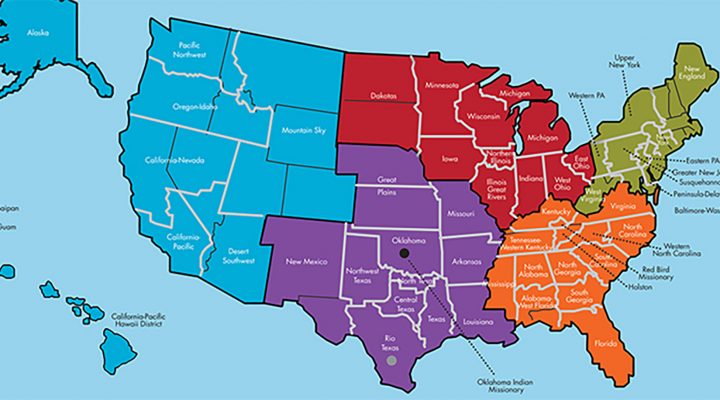

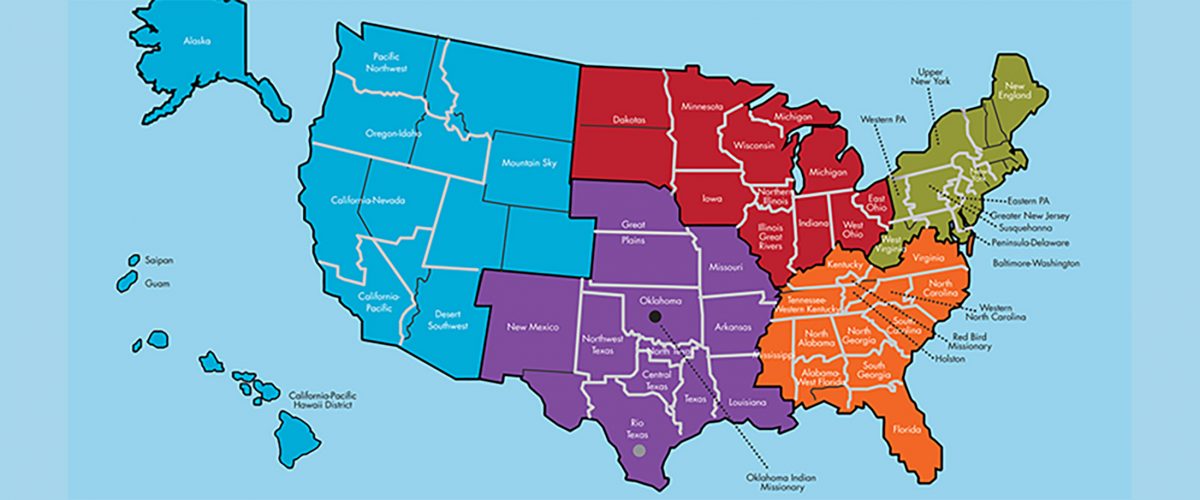

Bishop elections occur in geographically designated units known as jurisdictions. These are church regions composed of multiple states in which are located annual conferences, the UMC’s basic organizational unit. Names and boundaries of annual conferences don’t necessarily correspond to their states, such as Alabama-West Florida or Tennessee-Western Kentucky conferences. Jurisdictions typically meet at the same time because the time of a bishop’s election determines his or her tenure and seniority.

U.S. jurisdictions with states they cover and the sites of their 2024 sessions are:

- North Central, covering Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota and Wisconsin, meeting in Sioux Falls, S.D.; livestream.

- Northeastern, covering Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont and West Virginia, meeting in Pittsburgh, Pa.; livestream.

- South Central, covering Arkansas, Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas, meeting in Rogers, Ark.; no livestream listed.

- Southeastern, covering Alabama. Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, Tennessee, South Carolina and Virginia, meeting in Lake Junaluska, N.C.;

- Western, covering Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Guam, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington and Wyoming, meeting in Spokane, Wash.; livestream.

As jurisdictions prepare to convene, the UMC is responding to several major impacts since 2019.

First, a special General Conference in 2019 tightened the UMC’s anti-LGBTQ laws and policies, igniting a storm of protest from U.S. United Methodists. From 2020 to 2022, the global coronavirus pandemic delayed General Conference’s session three times until 2024.

The third of those delays in 2022 prompted a dissident organization, the Wesleyan Covenant Association, to establish a breakaway denomination, the Global Methodist Church, and to convince disaffected United Methodist churches to leave the denomination under an exit process adopted at the 2019 General Conference. Subsequently, 7,600 U.S. churches, or 25% of the denomination, departed the UMC, drastically reducing its financial resources.

At this year’s General Conference, another major impact occurred. Delegates voted to rescind and/or remove all the UMC’s anti-LGBTQ policies, including prohibitions against UMC pastors performing same-sex marriages and allowing same-sex marriage in United Methodist churches.

Because of declining financial resources, 2024 General Conference delegates adopted a 2025-2028 budget set at $373.4 million. That total represents a 38% to 42% decrease from the $604 million budget adopted in 2016, the budget under which the UMC has been operating since then despite declining revenues. The UMC’s 2025-2028 budget rests upon a contingency: annual conferences must achieve 90% collection of required annual contributions known as “apportionments” that fund churchwide administration, ministry and mission.

As part of budget deliberations, a unit within the denomination, the Interjurisdictional Committee on the Episcopacy, recommended the UMC reduce the number of U.S. bishops from 39 to 32. The reduction was calculated according to expected revenues for the Episcopal Fund, a designated account within the denomination’s budget that pays for bishops’ salaries, office expenses and health and pension benefits for active and retired bishops, their surviving spouses and minor children of deceased bishops. Currently the Episcopal Fund budget is set at $87.4 million, which could decline to $82.8 million if the 90% collection rate isn’t met.

Despite the added administrative burden on bishops who will serve more churches over wider geographic areas, General Conference delegates voted 631 to 65 to distribute U.S. bishops as follows:

- Southeastern Jurisdiction: Nine

- Northeastern Jurisdiction: Six

- North Central Jurisdiction: Six

- South Central Jurisdiction: Six

- Western Jurisdiction: Five

The Interjurisdictional Committee announced a plan July 3 for assigning the reduced number of U.S. bishops. The release noted: “Since General Conference, the Executive Committee of the Interjurisdictional Committee on Episcopacy has met five times and consulted with each bishop regarding transfer. The ICOE has discovered either an unwillingness or inability to transfer any bishops through the process outlined in the Discipline. The Discipline clearly states, ‘No bishop shall be transferred unless the bishop shall have specifically consented.'”

In other words, no bishop wanted to be transferred to another geographic area to fill a vacancy.

No bishop wanted to be transferred to another geographic area to fill a vacancy.

Since General Conference, two vacancies have occurred. Bishop Frank Beard of the Illinois Great Rivers Conference (southern Illinois), requested to go on long-term disability because of his ongoing battle with glaucoma. Bishop Robert Schnase, who oversees the Rio Texas (Southwestern Texas) and New Mexico conferences, unexpectedly announced his retirement July 1. Both decisions made it possible for their jurisdictions, North Central and South Central respectively, to assign remaining bishops without having to transfer anyone to meet the limit set by General Conference.

Meanwhile, although General Conference delegates expected there would be no election of new bishops this year, the refusal of bishops to transfer left the Western Jurisdiction with two vacancies because of Bishops Karen P. Oliveto’s and Minerva G. Carcaño’s retirements. Thus Western Jurisdiction issued a call in mid-June for candidates to submit their profiles for delegates’ consideration.

The Interjurisdictional Committee on the Episcopacy also proposes a radical idea: assigning a bishop to serve in both the Northeastern and Southeastern Jurisdictions. There’s no provision for this kind of an assignment in United Methodist law and no precedent in practice. It’s possible that delegates in either or both Northeastern and Southeastern will vote to send the proposal to the UMC’s “high court,” the Judicial Council, to determine its legality. No one knows at this point whether this unusual assignment will work either legally or practically, but delegates in both jurisdictions are expected to debate the idea.

U.S. jurisdictions trace their history to the 1939 merger of three denominations — the Methodist Episcopal Church, the northern branch of American Methodism, with the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, which broke away in 1844 over slavery, and the Methodist Protestant Church. To secure the merger of the ME, South Church, delegates agree to create a racially segregated division known as the Central Jurisdiction. Black clergy were relegated to the Central Jurisdiction and could be appointed to Black churches anywhere in the United States. This arrangement allowed the white portion of the church, particularly the Southeastern and South Central Jurisdictions where the ME, South Church was prominent, to maintain racial segregation.

Related articles:

UMC General Conference removes much of LGBTQ restrictions in consensus vote

UMC gives first approval to restructuring plan

Most congregations exiting the UMC are white and located in the South