The conflict over acceptance of LGBTQ persons in The United Methodist Church has become a three-way fight — with even more contenders likely waiting to turn the bout into a battle royal between opposing American forces and the rest of the international denomination.

In a press release that has flown under the radar of most United Methodists, the denomination’s bishops in Africa issued a statement Nov. 5 saying they intend “to make our own choices” regarding the church’s future. Led by Bishop Eben Nhiwatiwa of Zimbabwe, the statement repudiates the effort by U.S. traditionalists to claim African United Methodism as monolithic allies in the denomination’s breakup.

What does the statement mean?

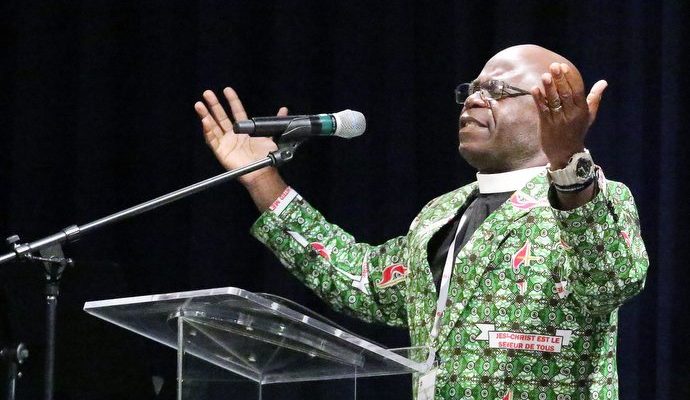

David W. Scott

While most in pew and pulpit took little interest in the African bishops’ statement, experienced observers caught the significance of the bishops’ assertion. Among them, David W. Scott offered the most cogent explanation for why a new stance by African church leaders could have a major impact on the church’s future. Scott, a United Methodist layman, serves as director of mission theology for the Atlanta-based General Board of Global Ministries and coordinates UM & Global, the collaborative blog of United Methodist Professors of Mission.

Scott cited three reasons why he and other observers find the African bishops’ statement so significant:

- “The bishops rejected the choice presented to them by the Protocol of Reconciliation and Grace through Separation.”

- “The bishops rebuked both American Traditionalists and American Centrists/Progressives.”

- “The bishops asserted their intention to set their own path.”

He added: “Thus, smart analysis of the political situation in The United Methodist Church should view it as a three-way conflict (with additional viewpoints held by smaller groups) instead of as a two-way conflict between U.S. Traditionalists and U.S. Centrists/Progressives.”

Traditionalists will feel the setback most keenly as African bishops assert their region’s right to equal participation in deciding United Methodism’s future.

History of African and American relationships in the UMC

“For decades, traditionalist United Methodists have courted Africans as their means to retain political power in a declining denomination.”

For decades, traditionalist United Methodists have courted Africans as their means to retain political power in a declining denomination. By church rules, the number of members in each regional unit known as an annual conference determines representation at the worldwide General Conference, United Methodism’s legislative body. U.S. traditionalists have seen their General Conference delegates decline as U.S. membership dwindled, while African delegates increased as the church continued to grow there.

Playing upon supposedly shared values, particularly in areas of gender identity and sexual behavior, U.S. traditionalists have long held pre-General Conference “orientation sessions” for African delegates. These sessions supposedly were to instruct African delegates on how General Conference works, but in reality they have been the equivalent of political rallies to tell African delegates how to vote on specific issues, especially resistance to LGBTQ inclusion.

As the denomination moved into the 21st century, however, African church leaders wised up to the fact that they were being used by U.S. forces to maintain political power. Cracks in the U.S.-African traditionalist coalition began appearing a decade or so ago, and now it seems that the widening rift has become a split.

Two recent influences

The African bishops’ statement can be traced to events involving two forces: a group led by the late Bishop John Yambasu of Sierra Leone, and the Africa Initiative of the Wesleyan Covenant Association.

Bishop John Yambasu. Photo by Paul Jeffrey, UMNS.

Bishop Yambasu was the driving force behind the Protocol for Reconciliation & Grace Through Separation. After nearly three-quarters of U.S. United Methodist soundly rejected the draconian punishments for violations of LGBTQ bans enacted at the disastrous 2019 Special General Conference, he felt called by God to try to reconcile United Methodism’s opposing forces, the bishop told church communicators. Calling together an ad hoc panel of representatives of conservative, centrist and progressive groups, Bishop Yambasu initially tried to keep them from splitting the church. However, during mediated negotiations the bishop became convinced that division was the only way to preserve at least a remnant of The United Methodist Church.

Bishop Yambasu led negotiations that resulted in what’s commonly known now as the Protocol. The proposal to divide United Methodism, which carries a significant benefit to traditionalist forces, appeared headed for sure passage at the 2020 General Conference until the coronavirus pandemic forced postponement of the legislative assembly.

Then in August of this year, Bishop Yambasu tragically was killed in an automobile accident on the way to preach at a pastor’s funeral in Sierra Leone. With its prime architect gone, the Protocol’s momentum has begun to dwindle during the delay of General Conference, now slated to be held Aug. 27-Sept. 7, 2021.

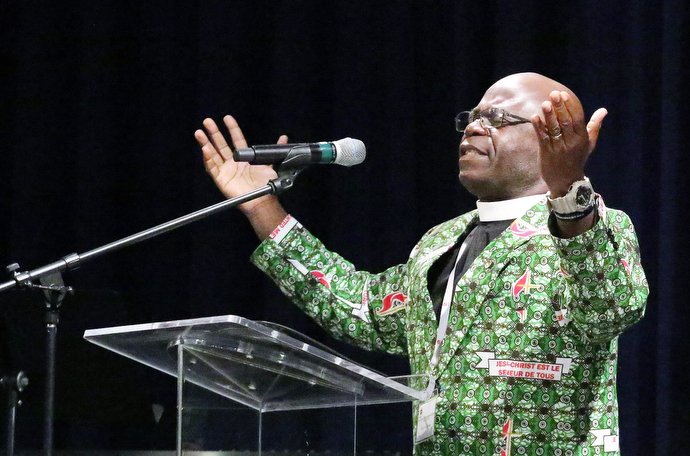

Forbes Matonga

Concurrent with the Protocol’s trajectory have been traditionalist efforts to shore up their African support, particularly over summer 2020 through a series of articles documented by David W. Scott. In particular, he cited an interview with Jerry Kulah, head of the Africa Initiative; an essay by Forbes Matonga of Zimbabwe; and two columns by Tom Lambrecht of the U.S. Good News faction. In essence, all these pieces have asserted that the Wesleyan Covenant Association’s Africa Initiative truly represents African United Methodists’ interests rather than the church’s duly elected bishops.

Of these efforts, Dr. Scott writes: “Thus, the Traditionalist argument is clear: United Methodists in Africa should affiliate with a new, Traditionalist denomination because of their views on sexuality. Even if their bishops oppose such a move, their leadership is illegitimate. …”

An assertion of full partnership

Against this background, the full import of the African bishops’ statement becomes clearer. Not only are they defending United Methodist unity, the bishops are asserting the right of African United Methodists to be full partners in decisions about the denomination’s future.

Furthermore, the African bishops aren’t alone in their demand for political equity. The U.S.-centric nature of The United Methodist Church has been challenged increasingly in the 21st century in everything from legislative proposals to updating the Social Principles, a set of faith-based guidelines for individual and communal human behavior.

Another proposal, the Christmas Covenant, emerged from United Methodists in the Philippines at the same time as the Protocol. Like the African bishops’ statement, the Christmas Covenant demands full parity in governance, particularly through its support for the creation of a regional conference that would allow U.S. United Methodists to decide their own interests in the same way that other international regions, known as Central Conferences, now are allowed to do.

However these forces play out, it’s clear that U.S. factions, both traditionalist and centrist/progressive, are being challenged to give up their dominance in church politics. Assuming the coronavirus pandemic allows General Conference 2021 to take place, the path to United Methodism’s future likely will be more tortuous to traverse than ever before.

Cynthia B. Astle is a veteran journalist who has covered the worldwide United Methodist Church at all levels for more than 30 years. She serves as editor of United Methodist Insight, an online journal she founded in 2011.

This story was made possible by gifts to the Mark Wingfield Fund for Interpretive Journalism.

Related articles:

Is the United Methodist separation still on?

Death of a bishop, birth of a new denomination intertwined for UMC

Another United Methodist plan demands patience more than specifics

Amid its own racist history, United Methodist Church unites against racism