I’ll never forget that moment. It was the late spring of 2008, and I was sitting in the pulpit of Covenant United Church of Christ in South Holland, Ill., where I had the privilege of serving for nearly eight years under the leadership of Ozzie E. Smith Jr., the founding pastor of the congregation. He was preaching the morning message — I cannot honestly recall the title or text — but in that moment, Rev. Ozzie began reflecting on his long-standing relationship with Jeremiah Wright Jr., and the influence Wright had on him as a father figure in the ministry. Rev. Ozzie was overcome with emotion, and he hollered out with a cry of grief. Immediately — as if on instinct — I began crying with him.

Paul Robeson Ford

The spring of 2008 marked the beginning of the most historic presidential primary season this nation has seen, as then-Sen. Barack Hussein Obama battled his Senate counterpart (and former first lady) Hillary Clinton for the Democratic nomination. After more than 35 years serving as senior pastor of Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago, Pastor Wright finally bid adieu to the church he had built from less than a hundred members to well over 6,000, with countless ministry initiatives that had impacted the city of Chicago, but also the nation and the world.

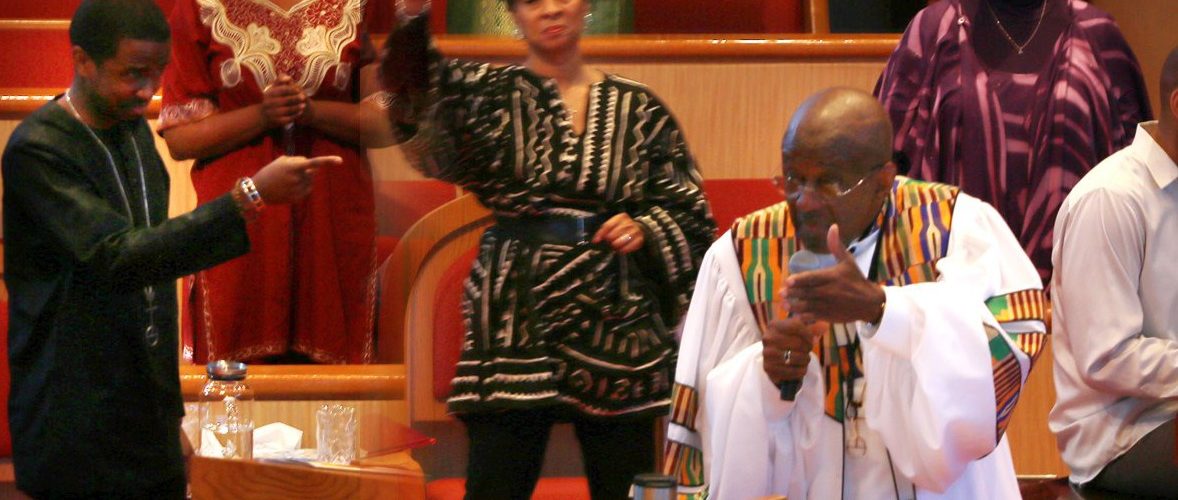

I was in the sanctuary of Trinity for several of the services in the last week of February that marked Wright’s departure from Trinity, as Otis Moss III — a prince of the pulpit himself — prepared to take over following a carefully designed and lengthy transition period. It was just days later that ABC’s Good Morning America began to run snippets of Wright’s most controversial sermon excerpts, wondering aloud if “the reverend could become a liability?” Other news media outlets quickly followed, fabricating a narrative that Wright was an anti-American, anti-Semitic Black boogeyman who hated white people and peddled in outlandish conspiracy theories.

As Frank A. Thomas has outlined in painstaking detail, the sermon snippets were taken completely out of context, and few in the media encouraged anyone watching to view the sermons in their entirety, or to consider the man’s track record as a minister and community activist. Millions of Americans were introduced to Wright as an angry Black caricature of a man they never had met before and did not know.

“Millions of Americans were introduced to Wright as an angry Black caricature of a man they never had met before and did not know.”

But hundreds of thousands of us knew Pastor Wright and his ministry well. I knew Wright as the vessel whom God had used to call me into the ministry as a junior in high school. I knew Wright as the man who had been my mentor and pastor since I arrived in Chicago in the fall of 2002 to begin formal training for ministry at the University of Chicago Divinity School.

He preached my ordination and installation as associate pastor at Covenant. I once scheduled a meeting with him to seek his perspective on issues of life and ministry that I was struggling to reconcile. I expected 30 minutes at most from a man who was so highly in demand. He gave me four hours of his undivided attention and counsel. Whenever I was in the wrong, he challenged me; whenever I was in the right, he supported me; whenever I was missing in action, he called me out by name from the pulpit, if necessary. This was the man who was being tarred and feathered by a media-fabricated controversy for the sole purpose of driving up ratings and creating headlines to make this historical presidential primary interesting.

This was the man whose plight brought me to tears that late spring morning.

All this history has come flooding back to the forefront of my mind as the fiercely fought battle between Raphael Warnock and Kelly Loeffler has led to a reprise of the same attack on a Black clergyman’s sermons, and by extension on the Black church as an institution.

Jonathon Walton has explained in clear and concise terms how we should best interpret these attacks that “misconstrue African American progressive and prophetic religious protest.” That is a generous understatement. Whether it be in 2008 or 2020, these attacks have sought to further marginalize leaders of the very community that built this country for free, while being subjected to untold inhumanities and brutalities because of the application of the Anglo-Saxon myth, and the white supremacist ideology that undergirded it. The half has never been told.

“As I have watched the news media coverage of the Georgia Senate race, I quickly realized this contest should have come with a trigger warning for people like me: You are about to relive your trauma.”

The cry of grief from Rev. Ozzie, and the tears I shed in response to that cry were rooted in a deep outrage and exasperation at the racist oppression that our people have suffered for more than 400 years. And as I have watched the news media coverage of the Georgia Senate race, I quickly realized this contest should have come with a trigger warning for people like me: You are about to relive your trauma.

I do not know Warnock like I know Pastor Wright, but I know the grief that those close to him and his ministry have endured during this time. It is unjust.

Whatever the outcome of Tuesday’s Senate election, as one duly ordained minister who has spent my entire pastoral career serving the Black church, it is important for me to state in no uncertain terms: Win or lose, we are going to keep preaching the truth without fear or favor.

Clergymen and women like me understand that we have a prophetic obligation to bring the politics of Jesus to bear on the nation in which we live and minister and the communities in which we serve. This is not an obligation we take lightly. As Dr. King lamented while explaining his public stand against the Vietnam War — alienating a host of friends and financial supporters of the Civil Rights Movement — “The calling to speak is often a vocation of agony; but we must speak.”

I experience this agony every time I mount the pulpit to utter words I know some people do not want to hear, will not be able to receive and are likely to reject. I have even been accused of “fomenting revolution from the pulpit.” The prophetic obligation was especially heavy upon all of us last year, as the unfinished work of racial justice exploded into the streets of American cities. We do not preach this way because we want to; we preach this way because we must, lest our God finds us unfaithful and unwilling to complete the task and be a “prophet to the nations” (Jeremiah 1:5).

As long as I have breath in my body, I will continue to preach in the spirit of the Prophet Jeremiah, the Pastor Jeremiah, and clergymen like King and Warnock. Win or lose an election, the Black church must stay true to who it is and who it has been for our people. As Kevin Cosby has put it, we are one of the five institutions that “sustain Black life,” and with the fragility of Black life on constant display, we cannot, and must not, waver in our commitment to speak and to speak boldly.

They’ll have to bury me before they silence me.

Paul Robeson Ford serves as senior pastor of First Baptist Church (Highland Avenue) in Winston-Salem, N.C. He was born and raised in New York City and grew up at the Riverside Church under the leadership of James A. Forbes Jr. He received a master of divinity degree from the Divinity School at the University of Chicago, where he is now a candidate for the Ph.D. in theology.