When the earliest Christians began to circulate writings expressing their unique faith, they made no concerted effort to tie the message of those writings in any essential way to the Greek language in which they were written. After all, the Jewish Scriptures that had been handed down to them, by which they grounded their faith in the tradition of Israel’s God, had largely come to them in translated versions, from the original Hebrew and Aramaic into the familiar Greek Septuagint.

“St. Jerome in His Study,” Domenico Ghirlandaio, 1480; in the church of Ognissanti, Florence.. (Encyclopædia Britannica)

The Christian writings themselves emphasized the gospel’s power to transcend language barriers, especially the Pentecost account in the Acts of the Apostles. The early centuries of the church saw translations in Syriac, Latin, Coptic, Ethiopic and many other languages as the Christian message spread through these various language groups. In the modern era, missionary movements and impulses have led to the translation of the Bible into hundreds of languages around the world.

Even in English-speaking cultures, where the Bible has long been available in vernacular versions, the enterprise of Bible translation continues unabated. The constant evolution of living languages provides some of the impetus for new versions, as each generation seeks to translate the Bible into the idiom of its age. This concern goes hand-in-hand with a continued missionary motive within much of Christianity for sharing the biblical message.

New translations may be prompted by other concerns as well. Translations offer the opportunity, for example, to read the biblical text in light of one’s own theological understandings and to make those understandings available to a wider audience.

Critical scholarship drives new translation due to research in several areas.

First, the discovery of new manuscript evidence frequently has called for reevaluation of the Hebrew and Greek texts on which modern translations are based. In addition, new understanding of the ancient languages in light of modern linguistic theory yields valuable insights about how the ancient texts functioned. Finally, some scholars seek to find a way to convey the unique oral effects, wordplay and rhetorical power of the texts that is elusive and often lost in translation, heeding the challenge of the ages-old warning that “translation is treason” (from the Italian pun and proverb “traduttore, traditore,”: “translator, traitor”).

Baptists in America have participated in translation efforts through the years impelled by all these various reasons: the missional, the modernizing, the theological, the text-critical, the linguistic, the performative and surely a few others as well. A few examples demonstrate the variety of concerns of various eras, in which some notable Baptists took part.

Spencer cone and the baptizo controversy

In the 1830s, Bible translators and the Bible societies and mission organizations that funded them experienced disagreements over the translation of the Greek word baptizo. Many Baptists called for translators to render this word with specific terms that indicated immersion, or dunking, with support from some linguists of the time, but also clearly in support of a theological position that equated baptism exclusively with immersion.

After approving financial support for Adoniram Judson’s Burmese translation that followed such a principle, British and American mission societies balked at sponsoring other translations that did the same. Their preference was to follow the principle established by the King James Version, simply transliterating baptizo as “baptize,” leaving the meaning ambiguous.

Spencer Cone

Objecting to this approach, Spencer Cone, a prominent New York Baptist pastor, resigned in 1836 as the corresponding secretary of the American Bible Society to lead in the formation of The American and Foreign Bible Society. Led by Baptists, this society was dedicated to being God’s instrument “in multiplying copies of pure versions of the Scriptures, and of counteracting the effects of corrupt and mutilated translations.”[1]

Even this new organization, however, was reluctant to issue a new English translation in place of the revered KJV and settled for publishing a New Testament with a supplementary page giving the Greek, the Authorized Version, and the “Proper meaning” of such words as “angel,” “Baptist,” “bishop,” “overseer,” “church,” “congregation” and “passover.”[2]

In 1849, disappointed with the AFBS’s unwillingness to print an extensive revision of the King James Version, Cone resigned and helped form the American Bible Union. After controversy over the incompetence of some assigned translators, the ABU appealed to more credible scholars and eventually published several editions of the New Testament.

This version finally accomplished the more thorough kinds of changes Cone desired. Matthew 3, for example, specified, “In those days came John the Immerser, preaching in the wilderness of Judea.” And, “Then went out to him Jerusalem, and all Judea, and all the region about the Jordan, and were immersed by him in the Jordan.” And, “When he saw many of the Pharisees and Sadducees coming to his immersion, he said to them … .”

Edgar Goodspeed’s American translation

By the 20th century, text-critical advances by scholars had changed the landscape of English Bible translation. With the publication in 1881 of a new version of the Greek New Testament by Oxford scholars B.F. Westcott and F.J.A. Hort, based in part on the discovery of important ancient manuscripts, a new British authorized translation of the English Bible appeared soon after as the Revised Version. An American counterpart, the American Standard Version, was published in 1901, but its woodenness (also characteristic of the RV) left an opening for American translators who wished to take advantage of this improved Greek text but also desired to update the language.

Edgar J. Goodspeed

Another scholarly insight was making its way into the conversation by this time, the recognition that the New Testament was not written in a distinct, sacralized dialect of Greek, but in the common Greek of the early Christian communities. Into this milieu came a Baptist scholar uniquely qualified to address the text-critical and linguistic concerns of that era, Edgar J. Goodspeed. A scholar of ancient papyri and languages, the University of Chicago professor also had a lifelong desire for conveying his scholarship in terms understandable to the masses outside of the academy.

Goodspeed published The New Testament: An American Translation in 1923, advancing the enterprise of English Bible translation along several fronts. As a scholar, he possessed the tools to take advantage of the updated manuscript evidence as well as the most recent linguistic insights into the koine Greek of the New Testament writers.

Having published and spoken extensively in popular forums, he further was capable of crafting a translation that spoke to the modern American idiom. The publication of Goodspeed’s American Translation became something of a media sensation in an era when newspapers and tabloids hungered for sensational stories, aided by savvy marketing by the University of Chicago Press.[3]

Not all the press was positive, as Goodspeed had challenged a sacred institution in the King James tradition. R. Bryan Bademan has argued the strong backlash against the American Translation was not driven primarily by theological concerns in the context of the liberal/conservative divide, but rather by aesthetic and cultural concerns.[4]

Nonetheless, the translation was a watershed in some respects, stimulating a public conversation in America about Bible translation and perhaps fostering an imagination in Americans for new traditions. Goodspeed subsequently was chosen as one of several Baptists to serve on the translation committee for the Revised Standard Version, and his translation had an influence on that enduring tradition.

The RSV, with a broad-based committee of translators, was based on many of the same principles as Goodspeed’s translation, but the denominational and institutional alignments of its translators and supporters led to its theological identification as a liberal, modernist translation.

From the RSV to the New Revised Standard Version to the recent New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition, this tradition has been a favorite in academic biblical scholarship as well as in Mainline denominations. Generations of college students encountered the RSV and NRSV traditions first in the ubiquitous Oxford Annotated Study Bible and later in the Harper Collins Study Bible (with its explicit connection to the Society of Biblical Literature) and other study Bibles from publishers identified with mainline denominations.

Eugene A. Nida with a chart explaining his Dynamic Bible Translation. (Eerdman)

Eugene Nida and Robert Bratcher and Dynamic Equivalence

A more recent revolution in Bible translation had Baptist scholar Eugene A. Nida as its central figure. Formally educated in Greek and linguistics, Nida joined with mission-minded linguists in the Summer Institute of Linguistics beginning in the 1930s, and then began a long career with the American Bible Society in 1943. His influence extended both to his approach to translation and to his method of training translators. Instead of having Western missionaries make translations for the people groups they served, he began training people from those groups to translate Scripture into their own languages.

In his approach to translation, Nida moved from a focus on word-by-word equivalents to an emphasis on conveying the message of the source language in the idiom, structure and style of the target language. This theory of “dynamic equivalence” (later known as “functional equivalence”) had implications not only for translating the Bible into languages in which it had not been previously translated, but also for English-language translations.

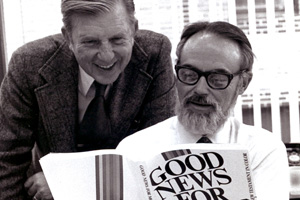

Robert Bratcher (right) with the Good News Bible (American Bible Society)

Nida tapped yet another Baptist, Robert Bratcher, to undertake a new English version incorporating this theory of translation. Bratcher single-handedly drafted the New Testament portion of this new work published by the American Bible Society. The result, Good News for Modern Man, was published in a casual format in 1966 and within five years had become the best selling paperback book in United States history.[5]

Bratcher went on to lead a translation team to complete a dynamic equivalence Old Testament translation, completing what would come to be known alternatively as the Good News Bible or Today’s English Version.

As translations have proliferated in the years since the introduction of the Good News Bible, one metric by which all versions are evaluated is their place along a continuum between formal (word for word) equivalence and functional (dynamic) equivalence. This measure is not an indicator of the value of the translation but a reflection of the preferences and values of the translators. Some such preferences may be tied to theological leanings, such as a link between formal equivalence and a verbal understanding of biblical inspiration, but they may also simply reflect a desire to reach particular audiences.

Advances in the reconstruction of the earliest Hebrew and Greek texts as well as in lexicography (determining word meanings in their ancient context) tend to be incremental today, compared to some of the leaps of understanding that have propelled translation activity in the past. But new translations still strive to incorporate those advances, and most of the major translations done by committees make incremental updates every few years.

Advances in the reconstruction of the earliest Hebrew and Greek texts as well as in lexicography (determining word meanings in their ancient context) tend to be incremental today, compared to some of the leaps of understanding that have propelled translation activity in the past. But new translations still strive to incorporate those advances, and most of the major translations done by committees make incremental updates every few years.

While choices about formal or functional equivalence and a commitment to recent textual and linguistic findings are not necessarily the province of particular theological camps, it is nonetheless still the case that most modern translations can be identified by the theological positions of their adherents. Theological commitments are often stated in the guiding principles of translation teams, and the denominational and institutional identifications of the translators, as well as their demographics in terms of race, gender and other affiliations generally signal the theological leanings of a particular version. The differences in translation are often subtle, but persistent.

Because of the great diversity of theological perspectives represented by persons who identify as Baptist, we could identify Baptists as participants in most of the committees of major translations embraced by Americans today.

This article originally appeared as an introduction to an issue of American Baptist Quarterly focused on Baptists and Bible Translation.

Dalen Jackson

Dalen Jackson served as founding academic dean and professor of biblical studies at Baptist Seminary of Kentucky and is now retired.

Related articles:

How to pick a Bible that’s right for you | Analysis by Mallory Challis

Crash-course in Bible history: How the Bible came to be | Analysis by Mallory Challis

After 30 years, the NRSV gets an update: Here’s what that means

1. Paul C. Gutjahr, An American Bible: A History of the Good Book in the United States, 1777-1880 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999), 107, quoting the first annual report of the AFBS.

2. Creighton Lacy, The Word Carrying Giant: The Growth of the American Bible Society (1816-1966) (Pasadena: William Carey Library, 1977), 90.

3. Bryan R. Bademan, “‛Monkeying with the Bible’: Edgar J. Goodspeed’s American Translation,” Sacred Heart University History Faculty Publications, Paper 12 (2006): 62, http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/his_fac/12.

4. Bademan, “Monkeying with the Bible”: 84, n. 19.

5. Eleanor Blau, “‘Good News’ Bible Leads Paperbacks,” New York Times, November 3, 1971, The New York Times Archives, https://www.nytimes.com/1971/11/03/archives/good-news-bible-leads-paperbacks.html.