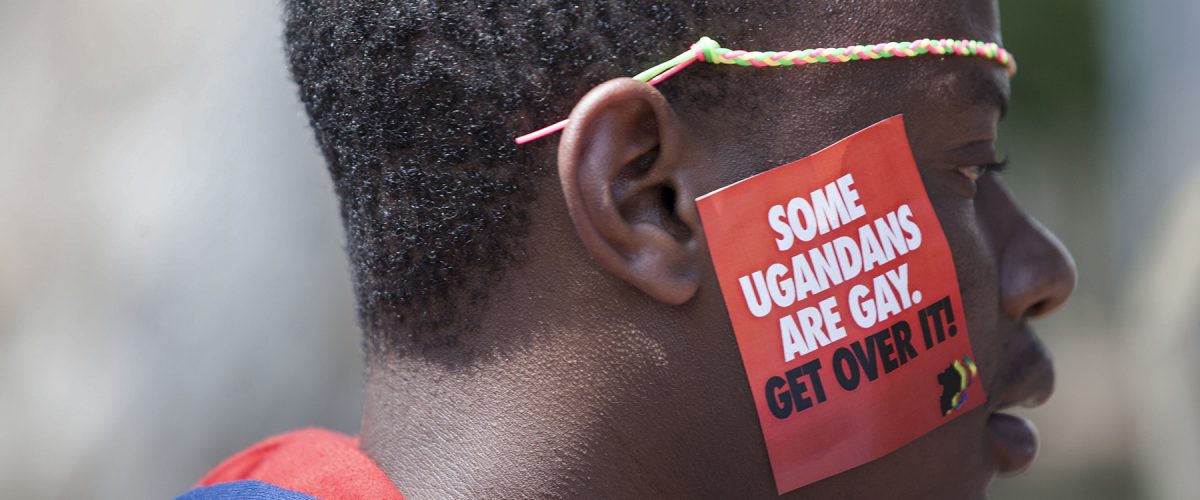

Eight years after an anti-LGBTQ bill passed by the Ugandan Parliament failed to see the light of day due to a court overruling it, Parliament March 21 passed another anti-gay bill after barely two weeks of consideration.

Asuman Basalirwa

Tagged as the “2023 Anti-Homosexuality Bill,” the legislation was introduced by Member of Parliament Asuman Basalirwa. While making a case in Parliament for the bill, Basalirwa urged his colleagues to join him in promulgating “a new law that addresses that cancer.”

The bill stipulates harsh penalties, including the death penalty or life imprisonment for LGBTQ persons and their allies found to have violated the law.

For the first time, it would make merely identifying as gay illegal and punishable by life in prison. And friends, family and members of the community would have a duty to report individuals in same-sex relationships to the authorities.

It would make merely identifying as gay illegal and punishable by life in prison.

The offense of “aggravated homosexuality” would carry the death penalty. Aggravated homosexuality is outlined as sexual relations involving those infected with HIV, with minors and with other vulnerable people. Even “attempted aggravated homosexuality” could produce a 14-year jail sentence.

It has been called the strictest ant-gay law in all of Africa, passed in a country where it already is illegal to engage in same-sex relations due to colonial-era regulations.

Yoweri Museveni

To become law, the bill must be signed by Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni. That appears certain to happen, as Museveni approved the 2014 Anti-Homosexuality Bill that later was voided by the court because it had been adopted with less than the constitutionally required number of members of Parliament voting.

However, Museveni faces enormous pressure from the country’s Western allies, who have threatened to cut off aid to Uganda if the bill becomes law.

On March 16, in an address to Parliament, Museveni addressed the gay issue: “The homosexuals are deviations from normal. This deviant, is he deviant by nature or nurture? We need a medical opinion on that.” He then advised “Western countries” to “stop wasting the time of humanity by trying to impose their practices on other people.”

Before the new bill’s presentation in Parliament, public awareness on LGBTQ issues was raised by both politicians and religious leaders, who warned of the influence of Western cultural agendas hiding under the cover of humanitarian aid and human rights.

Reports circulated in Parliament about students and teachers who were alleged to be gay. Anita Among, speaker of Parliament, urged the Committee of Education to look into these allegations: “Pick interest in that story that is on social media on the issue of the gays, where a teacher is being transferred from one school to the other because of being a gay and you (transfer) the character from one school to the other. Can you pick up that issue? We are killing our morals. … Pick up that issue and report back to this house on those schools that are being mentioned.”

Anita Among

Speaker Among, at another event, said: “As an institution of this country that passes the laws, tomorrow we are going to bring a bill on anti-homosexuality and I want to request the religious leaders, that this time around, be there to see who is who. … We will not allow announcement of quorum. We are going to vote by show of hands. You are either for homosexuality or you are against (it). We want to see the kind of leaders we have for this country, and I want to promise you I will stand by that.”

The Inter Religious Council of Uganda — comprising Christian and Muslim groups — also had its members calling for the government to enact anti-gay laws. Among them were Stephen Samuel Kaziimba Mugalu, Anglican archbishop of Uganda.

After the recent decision of the Church of England to bless same-sex unions, Mugalu wrote a rejoinder where he advised Ugandan students and teachers to be wary of being exploited by foreign organizations.

“Now that our children are back in school, beware of the well-funded gay organizations that are recruiting our children into homosexuality. Not only in Kampala, but all over the country,” he advised. “They target our poverty and promise our youth money.

“To our youth — if someone invites you to a function and offers you a big transport refund, those are probably bad people. Say ‘no’ to it. And, if you have already been exploited or abused by such groups, please go to your bishop for prayer, support and guidance. You will be received with love and compassion.”

To the head teachers, he said: “If an organization is bringing money and resources to your school, or inviting your students to a function, do your research. Make sure you know who they really are.”

He and other Ugandan leaders said Ugandan children were being lured into homosexuality by sinister outside forces.

“We cannot serve God and mammon. We cannot serve God and money. Do not lose your soul because you think you will gain the whole world through the money they offer you,” the archbishop said. “Do not think you can take the money but not fall into their trap. It’s a lie; you are being exploited with that money.”

Not all Ugandan elected officials supported the new anti-gay bill. Some worried the penalties are too harsh, especially since existing laws prohibit same-sex relations.

According to the Monitor newspaper, “While the attorney general, Mr. Kiryowa Kiwanuka, labeled the bill redundant due to multiple repetitions of offenses in already existing legislation, the minister of state for disability affairs, Ms. Grace Hellen Asamo, and the minister of state for ethics and integrity, Ms. Rose Akello, said the new law is necessary to ensure more punitive penalties.”

According to Human Rights Watch, the 2023 Anti-Homosexuality Bill is a “revised and more egregious version of the 2014 Anti-Homosexuality Act, which reinforced existing prison sentences for same-sex conduct and outlawed the “promotion of homosexuality.”

“It criminalizes people simply for being who they are.”

Oryem Nyeko, Uganda researcher at Human Rights Watch, pointed out that “one of the most extreme features of this new bill is that it criminalizes people simply for being who they are as well as further infringing on the rights to privacy and freedoms of expression and association that are already compromised in Uganda.”

He urged Ugandan politicians to “focus on passing laws that protect vulnerable minorities and affirm fundamental rights and stop targeting LGBT people for political capital.”

Ruth Atim, a Ugandan journalist, told BNG: “If this bill becomes law, it will likely result in more violence against LGBTQ people, who already experience a great deal of violence. It will also infringe on a number of fundamental rights, including the freedom of association and expression, privacy, equality and nondiscrimination.”

Caleb Okereke, a Nigerian journalist and co-founder of Minority Africa, an organization that focuses on minority stories across Africa, believes American evangelicals contributed to the homophobic sentiment on the African continent through their preaching. In a recent article published by Foreign Policy, Okereke argued that “from the days of European colonialism, when sodomy warranted the death penalty, the church has been the face of the anti-LGBTQ movement and has deployed language and framing consistent with present-day ex-gay movements.”

He also said: “The church has been involved in manufacturing and sustaining the ex-gay framework in more than subtle and metaphorical ways. Evangelical preachers have traveled across Africa, verbalizing this harmful language.”

He mentioned American evangelical Scott Lively as being “part of a series of anti-gay events” that culminated in Uganda’s 2009 “Kill the Gays” bill, which first called for the death penalty for those found guilty of “aggravated homosexuality.”

“If gay people are not successfully framed as predators, then extreme measures against them could be questioned,” Okereke said. “However, the violence that LGBTQ people experience in Africa has been justified by these anti-gay groups through the construction of a narrative of intent by them to target children.”

Anthony Akaeze is a Nigerian-born freelance journalist who lives in Houston. He covers Africa for BNG.

Related articles:

In stunning development, United Methodist African bishops repudiate separatist group

Ghana considers a new law punishing same-sex relations, and LGBTQ community fears reprisals

African Anglican leaders criticize Church of England over same-sex marriage decision