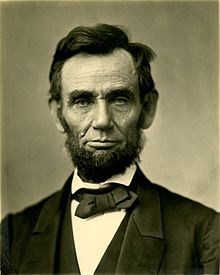

One rainy Washington night in February 1862, Abraham Lincoln groaned in deep grief. Yes, there were the mounting casualties in the War Between the States, but closer to home, Willie, his 11-year old son, had died of typhoid fever despite the excellent nursing care of Rebecca Pomeroy. Now his son Tad, age 9, was fighting for life. And Lincoln had buried Eddie, a 4-year old son, back in Springfield.

“I cannot lose another boy,” he moaned. Life was demanding too much from him that February night.

Harold Ivan Smith

Washington was not a safe place for women to walk at night. So when it was time for Mrs. Pomeroy to return to the hospital where she stayed, Lincoln said he would get a buggy and take her back.

Because of heavy rains, Washington’s “streets” had turned to mud. Soon, even the skilled Lincoln found the buggy mired in the mud. He struggled to get the horses to pull the buggy free. The buggy sank deeper in the mud.

Frustrated, Lincoln said, “Mrs. Pomeroy, you stay here. I’ll be back.” He rolled up his pants legs and stepped down into the mud and disappeared into the darkness. He was gone a long time. Finally, he reappeared carrying large flat stones, which he carefully spaced in the mud.

Then Lincoln stretched out his hand. “Mrs. Pomeroy, if you’ll take my hand, and step where I point, I will get you to the sidewalk without your dress getting muddied. Then I’ll get the buggy out and we’ll be back on our way.”

Mrs. Pomeroy carefully stepped stone by stone until she reached the sidewalk. Now, the buggy lighter, Lincoln nudged the horses to pull it free.

“Mud. Deep mud. That’s what some of us are facing this holiday season.”

Mud. Deep mud. That’s what some of us are facing this holiday season. In our loss —or losses in some cases — there seems to be no solid ground on which to stand, only mud. Every day we feel like we are sinking deeper into the mud. We cannot see any hint of a future in grief’s darkness.

How do grievers get from here in the mud — a place we never volunteered to be — to there, a safer place?

When sunk in the mud of grief, someone — or someones — whether family member, friend or neighbor, wants to “fix” you. Or urges you, “Move on.” Easy for them to say.

And they offer a bouquet of cliches: “They’re in a better place … They are out of their suffering … They wouldn’t want you to be taking this so hard.” All of which are really ways of saying, “They wouldn’t want you making me uncomfortable.”

Years ago, an angry widow demanded, “How do they know that? Do they have a note saying, “Tell her, I’m in ‘a better place’?”

Some of you are “grief rookies.” This is your first time stuck in grief. Do you have a Lincoln to help you get safely to the sidewalk?

Not long after that particular night, Lincoln was so exhausted, so distraught as he watched at his son’s bedside: Would Tad die or live? His wife, Mary Lincoln, was no source of comfort. She was hysterical all day, then wailed and wept inconsolably into the nights.

Not long after that particular night, Lincoln was so exhausted, so distraught as he watched at his son’s bedside: Would Tad die or live? His wife, Mary Lincoln, was no source of comfort. She was hysterical all day, then wailed and wept inconsolably into the nights.

For hours Lincoln sat by Tad’s bed watching, waiting, worrying. At some point, he posed this question: “Mrs. Pomeroy, how have you dealt with your husband’s death and your son’s death? And now you don’t even know where your soldier son is. Is he safe somewhere? Has he been wounded? How do you have the strength to get up each morning and take care of my son?”

“Mrs. Pomeroy was not a grief counselor, but she had experienced what poets call ‘the cup of deep sorrow.”’

Mrs. Pomeroy was not a grief counselor, but she had experienced what poets call “the cup of deep sorrow.” That night, out of her experience of loss as a widow and a mother, she had an opportunity to offer “stones” to the president.

She urged Lincoln, “You must go to God, Mr. President, for strength. He will help you.” Hmmm. Abraham Lincoln was not a religious man. In fact, he could not get his mind around a God who would let a little boy like Willie suffer and die or who might let Tad die.

Slowly, very slowly, Lincoln came to understand the wisdom of Mrs. Pomeroy’s words, of her “stones.”

One who had been deep in the mud of grief was sharing what she had learned, almost like the early disciples answered in Acts 3:6, “Silver and gold have I none, but such as I have, I give you.”

Tad survived the typhoid fever only to die nine years later at age 18. Two sons and then a husband assassinated before her eyes — little wonder Mary Lincoln lost her mind for a season. I suspect she did not have someone offering smooth flat stones upon which she could stand.

So, what are some stones that might help you this holiday season? Here are four stones I have found support grievers:

“The most honest prayer this holiday season may be, ‘Oh, God.’”

The first stone is prayer. A wonderful Jewish rabbi who has experienced grief’s mud taught me an amazing prayer that you can memorize in about three seconds: “God, stay close.” You may protest, “I cannot pray.” Eleanor Roosevelt often said, “Pray as you can, not as you can’t.” The most honest prayer this holiday season may be, “Oh, God.” And if you are angry at God, if you are not “on speaking terms” at the moment, that’s OK.

The second stone is remembering. Has anyone suggested, “Best not to dwell on this; you’ve just got to go on and live your life the best way you can”? Some individuals collude to distract you from your grief so you won’t “spoil” the holidays for others. They may plot, “Now, whatever you do, don’t mention the name of the deceased.”

Some will want to go through a holiday meal or get-together and never mention that name — or the names — that mean so much to you. I have long told grievers that an individual is not “gone” until two things happen: You stop saying the name and you stop telling stories about them. But, as a griever, you may have to break the ice and mention the name.

The third stone is cry. Do you remember Leslie Gore’s hit lyric, “It’s my party and I’ll cry if I want to … . You would cry too if it happened to you”? And her joy when she sang, “Now, it’s Kathy’s turn to cry”? Everyone’s turn to cry in grief comes along, later or sooner. Might you adapt Gore’s words, “It’s my grief and I’ll cry if I want to, cry if I want to”? Grievers learn that if you even look like you are going to cry, someone will dive for a box of tissue to thrust at you. So grievers cry in the shower so their tears will be drowned out. Grievers cry in their car. Grievers squelch the tears to avoid making someone “uncomfortable.”

Cry. Fritz Perls, a noted psychologist, rightly observed, “For every tear that is not expressed here (the eyes), it will seek and find its ultimate revenge somewhere in the body.”

“Every Thursday morning, Abraham Lincoln made his way to the Green Room in the White House, locked the door behind him, and sobbed.”

Every Thursday morning, Abraham Lincoln made his way to the Green Room in the White House, locked the door behind him, and sobbed. One hour every Thursday morning was Lincoln’s “turn” to cry. You have permission to cry!

The fourth stone is gratitude. The suggestion to “make gratitude” may annoy or offend you. “And just what do I have to be grateful for?” That’s a fair question many grievers have asked me over my years as a grief care professional.

At times, I have answered, Might you be grateful that you had 39 years of marriage? Because not everyone gets 39 years. Might you be grateful that it was a good marriage? Might you be grateful that you have a roof over your head? Might you be grateful for your own health? Might you be grateful that you had a son or daughter or grandchild who brought laughter to your heart? Might you be grateful that there were no words left unspoken between you and the deceased? Might you be grateful that you held hands as the deceased crossed worlds?

A wise psychologist at Columbia University taught me to ask grievers for this commitment: “Would you be willing to decide that every night for the next 30 nights, before you fall asleep, you will name three things that you are grateful for?” I often have followed that request with a statement: Perhaps you recall the words Irving Berlin wrote in 1944, in the darkness of World War II, “And I fall asleep counting my blessings.”

Here’s the reality: You may not feel you have anything to be thankful for right now but, gradually, by naming one gratitude, you may find a way to trust this stone, too. Making gratitude changes the soil of your heart and your soul; it changes the environment in which you grieve.

“Stones laid in the mud, in the darkness of this holiday season will not ‘fix’ you. But these stones may be resources to get you to a safe or safer place.”

Stones laid in the mud, in the darkness of this holiday season will not “fix” you. But these stones may be resources to get you to a safe or safer place.

In those first days and weeks and months in grief’s mud after her husband’s death and her son’s death, Mrs. Pomeroy never had imagined that someday the president of the United States would ask her how to deal with grief.

This may be difficult for you to imagine in the intensity of your grief, but someday individuals will ask you the question that Abraham Lincoln asked Rebecca Pomeroy, “How did you get through it?”

“You’re asking me? I am not sure I am even through it. I’m not sure I will ever be through it.”

It would not surprise me that if you “lean” into your grief your grief has lessons to teach. Grief either stretches or shrinks the soul. Your experience can contain lessons that will someday become “stones” to those who are grief rookies.

For now, these four stones may help you get to a slightly better “there.”

Some of us will need to get out of the “buggy” and go find the stones to make a safe path to the sidewalk.

Some of us will need to step out of the buggy and onto those stones, trusting the stones will hold us up.

Grief during the holidays is tough, perhaps the toughest thing you will ever do. But what is grief? The flip side of the coin called love.

May all your stones this season be solid.

Harold Ivan Smith is thanatologist and independent scholar whose research focuses on the grief of U.S. presidents and first ladies. For 18 years he served on the teaching faculty of Saint Luke’s Hospital in Kansas City, Mo. He earned graduate degrees from Scarritt College, Vanderbilt University, and a doctor of ministry degree from Asbury Theological Seminary. His writings include A Decembered Grief, On Grieving the Death of a Father; Grieving the Death of a Mother; When You Don’t Know What to Say; When a Child You Know Is Grieving, When Your People Are Grieving: Leading in Times of Loss.

Related article:

Getting into the holiday spirit is hard this year | Ella Wall Prichard