I am an unabashed 1980s baby. My childhood was blessed with He-Man, Transformers, G.I. Joe, and the then-wrestlers from the National Wrestling Alliance, American Wrestling Alliance and the World Wrestling Federation.

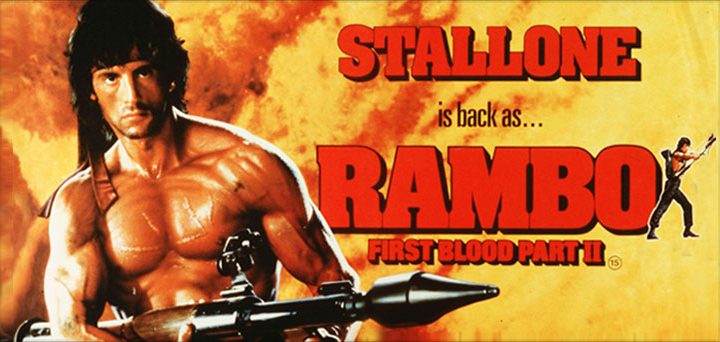

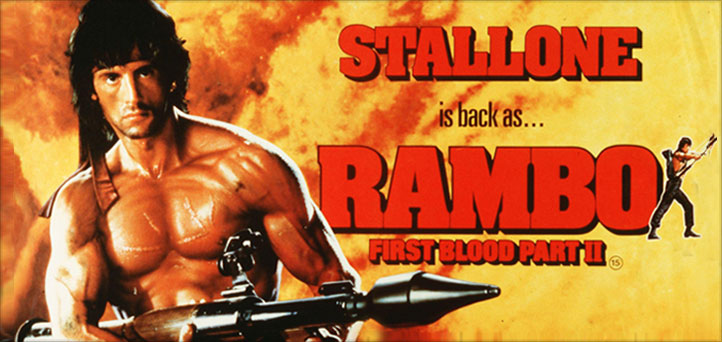

I grew up memorizing movie lines and moves by Chuck Norris, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone. In addition, I also was privy to the musical stylings of Hip-Hop. Legendary MCs like Kool Moe Dee, Run DMC, and LL Kool J provided the soundtrack for my childhood adventures.

Napoleon Harris

All throughout the ’80s these larger-than-life men represented the embodiment of manhood. From the captivating rants and swagger-soaked struts of the Nature Boy Ric Flair, to the bullish bravado and bulging muscles of Rambo, the ’80s were a time in which real alpha males were on full display.

Similarly, the ’80s were a time in which guns were on full display. As a child I grew up playing with little green army men each holding weapons. Toy revolvers and life-like guns were all the rage and could be purchased from grocery stores or toy stores. The Transformer toys and G.I. Joe toys also came with advanced weapons-guns. As a child of the era, guns were as natural as well, being a guy.

“As a child of the era, guns were as natural as well, being a guy.”

In reflection of that era, pop culture meted out a construct of manhood that always was earned at the expense of someone else. It was as if society took its cue from Ric Flair, who famously posited, “To be the man, you’ve got to beat the man” as he defended his NWA heavyweight championship belt weekly on television.

Manhood became a status symbol, a construct earned by beating someone physically, outsmarting someone in a Ferris Bueller chicanery manner, through abusing one’s own self by drinking or smoking excessively, or through sexual conquest at the expense of women. In all ways, manhood was achieved as the result of domination and asserting one’s will over and against a human body.

The ’90s and new millennium kept the same energy. Manhood was earned at the expense of someone else, either through physical domination or misogynistic exploits. The only thing that changed was the messengers of the same established social mis-norm of manhood. The cartoonesque WWF became the edgier R-rated WWE, the carefree B-Boy era of Hip-Hop became the gangster-infused stylings of Snoop Dogg and Biggie Smalls. Urban movies like Menace to Society and Boyz in the Hood gave kids like me new silver screen heroes but the messaging remained the same: Manhood earned at the expense of someone else.

The social normalization of guns remained a constant as well. Through televised violence, immortalization of on-screen violence through Hollywood, and the continued reporting of scintillating tales of violence via 24-hour news outlets, gun violence was as American as apple pie.

Perhaps, in fairness, the ’90s and ensuing new millennium became a time of increased fascination with guns. Video games gave kids like me the opportunity to employ them to assert our electronic will on others regularly. Music at the time also made odes to guns. In this era, mass shootings at schools actually became the new American tradition.

“I am convinced our cultural definition of manhood is directly responsible for the national obsession with guns.”

I am convinced our cultural definition of manhood is directly responsible for the national obsession with guns. Since manhood has been equated to being a status that must be gained at the expense of the other and only obtained by domination, guns have become essential. They are the tools by which masculinity is assembled and maintained.

How else could one explain the psychology of America housing more guns than national residents? There is an explicit link between guns and guys because the existence of one necessitates the other.

What is necessary is a total deconstruction of the concept of masculinity (manhood, “guydom”). It has to be completely reset and reconfigured so that it is no longer achieved by domination and force.

Sadly, the road to reconstruction doesn’t lead to religion as commonly construed in America. American Christianity has been an accomplice in malforming masculinity.

The traditionally Americanized God is held as the ultimate victor and conqueror who violently obliterates any opposition from the Egyptians, to the unnamed hodge-podge of people constructing a tower at Babel, to the other-worldly beasts in John’s Revelation. Americanized God demonstrates his god-ness through domination and violence.

In America, given our brutal history from the false Doctrine of Discovery to the broken construct of Manifest Destiny, to the current abomination of American triumphalism (Christian nationalism) we need a hard theological reset.

We must ask: Have we made a false god in our own image, or has the Americanized god of our understanding reduced us to his? Is this a god at all? Because this is certainly not a good god or one that deserves our allegiance.

“This is not the God at the heart of Judeo-Christianity or the Bible for that matter.”

Moreover, as a pastor I feel obligated to say this is not the God at the heart of Judeo-Christianity or the Bible for that matter.

There is an unrelenting haunting trinity of guys, guns and God in America. As it stands, guys need guns to cement their manhood because it is God’s will — or at the least it is God’s way. And it is precisely this order of thinking that has made America such a dangerous place to exist.

We need a new ideology, one that isn’t centered on a violent and oppressive God, because violence doesn’t birth peace. Perhaps now is a good time to rediscover the God of Christian Scripture. This God demonstrates power not by dominating people but by entering into loving covenant with them. This God expressed most tangibly in Jesus of Nazareth suffers, heals, feeds and loves.

In Christ, we see the manifestation of a new and improved manhood one characterized by vulnerability, the embrace and expression of emotions (not just anger), and community.

“In Jesus, we see don’t find a manhood earned at the expense of women.”

In Jesus, we don’t find a manhood earned at the expense of women, but rather a manhood that exists in partnership with women, one that is cultivated by the input of women, a manhood that maintains healthy relationships with women.

Perhaps vulnerability, living in community with all people, and loving service to others can become the new marks of manhood. It appears Jesus certainly believed so. After all, in the Bible he referred to himself as the “Son of Man,” a term which technically meant “the man.” Hence Jesus is, well the man, the model of manhood we need.

In Jesus we find a pattern for manhood in which men can be vulnerable, free to express emotions other than hostility and anger. Where men can be afraid or experience joy outside of having dominated in a sport. In Jesus we find a pattern for being a guy that allows men to be fully alive — open and available to fix, heal, love and suffer alongside others as a part of a community.

With a new or radical (as in back to the root) understanding of God, we can begin to recapitulate an ensuing new understanding of manhood that doesn’t center around domination but around community and vulnerability.

This type of guy has no ontological obsessive need for guns because he seeks a peace that never could come from violence.

This type of manhood is secured because it does not have to be procured at the expense of another and therefore does not have to be defended or paraded like a badge of honor, like a heavy weight championship belt.

This is the type of manhood that should be celebrated in song and enshrined on film. We’ve had far too much of the guys, guns and God, and it has not fared well for us. It’s time for something else.

Napoleon Harris serves as pastor of Antioch Baptist Church in his hometown of Cleveland, Ohio. He is a graduate of Tennessee State University and Vanderbilt University Divinity School, an avid reader, writer, Omega Man, and devoted husband and father.

Related articles:

We’ve been sold a sampled gospel | Opinion by Napoleon Harris

Jesus and John Wayne exposes militant masculinity in the age of Trump | Analysis by Alan Bean

Christian masculinity, culture and racism: An interview with Kristin Du Mez | Opinion by Greg Garrett