“For the last 20 years, I thought if there was a God, he probably hated me for making me the way I am.”

I can’t communicate the destructive power those words had on me. Back then, I was a conservative, non-affirming pastor serving a non-affirming Southern Baptist Convention church, and in one sentence, 29 syllables, only seven or eight seconds, all my imaginations of being a “kinder gentler evangelical” were annihilated.

Jason Koon

Maybe I never had personally caused this kind of harm to anyone. I mean, here I was, sitting with him, eating lunch, laughing at his jokes, listening to his story. But I knew the people I sided with, the positions I elevated, my unflinching assertion about the “clarity of Scripture” had done this to him.

For more than an hour, he told me about how he had gone to his pastor, asking for prayer and guidance about the “same-sex attraction” he was experiencing. Gary told me he thought he was doing everything right. He didn’t want to be gay. He wanted the feelings to go away, prayed for it, begged God to take them. He thought his pastor would see this and appreciate the effort he was making.

Instead, Gary was pathologized. He no longer was welcome at church, and his closest friends were counseled to terminate their relationships with him. Gary had woken up that morning a committed church member, a model of what a young Christian man ought to be. He went to bed that night an outcast — hopeless, suddenly thinking God’s love might not be for everyone after all.

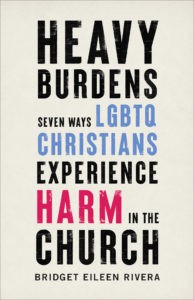

Gary is far from alone. In her debut book, Heavy Burdens: Seven Ways LGBTQ Christians Experience Harm in the Church, Bridget Eileen Rivera cites several troubling statistics linking suicidal ideation among LGBTQ youth to church involvement. While the likelihood of a young person attempting suicide drops with religious involvement among almost every demographic group, it jumps by 38% among LGBTQ young people. When conversion therapy enters the equation, that number skyrockets even higher. In 2019, approximately 12% of LGBTQ youth attempted suicide; among those who endured conversion therapy, that number was close to 30%.

Gary is far from alone. In her debut book, Heavy Burdens: Seven Ways LGBTQ Christians Experience Harm in the Church, Bridget Eileen Rivera cites several troubling statistics linking suicidal ideation among LGBTQ youth to church involvement. While the likelihood of a young person attempting suicide drops with religious involvement among almost every demographic group, it jumps by 38% among LGBTQ young people. When conversion therapy enters the equation, that number skyrockets even higher. In 2019, approximately 12% of LGBTQ youth attempted suicide; among those who endured conversion therapy, that number was close to 30%.

Rivera rightly lays much of the responsibility for this epidemic of suicide and mental illness among queer Christian young people directly at the feet of many churches and Christians whose attitudes and assumptions pathologize queerness. Invoking Jesus’ indictment of the Pharisees in Matthew’s Gospel, she argues that these attitudes and assumptions lay unbearably heavy burdens on the shoulders of countless LGBTQ Christians.

“They tie up heavy burdens,” Jesus says, “and lay them on people’s shoulders, but they themselves are not willing to move them with their fingers.”

The key to reversing this, according to Rivera, is refocusing conversations around queerness away from the question of sin.

“Do queer people sin?” Rivera writes. “Of course. Do they sometimes sin in ways that differ from straight and cisgender people? Once again, of course.”

However, by characterizing sin as anomalous in straight people but endemic in LGBTQ people, these debates further pathologize queerness, adding more weight onto the shoulders of LGBTQ Christians. Instead, Rivera argues that we must shift the conversation away from the question of sin, creating safe spaces in our faith communities where we can all humbly and patiently work through the complexities of how faith interacts with sexuality and gender. Only when we are willing to create space for those who may not see things the same way we do can we begin to reverse the centuries-long legacy of harm churches have inflicted on queer people.

“I listened, and I came around eventually. I think it was the day Gary told me he had started praying again.”

I didn’t change my thinking immediately. For months, Gary and I went back and forth on issues like celibacy and same-sex attraction, commitment and the countless ways churches victimize queer people. But I listened, and I came around eventually. I think it was the day Gary told me he had started praying again. He was still gay. He was still attracted to men and had no intentions of living a life of celibacy. But at that moment, I just didn’t care anymore. He was reconnecting with God, and that was an objectively good thing.

Rivera is right. Until our churches become spaces where people can work through the complex issues surrounding spirituality’s intersection with gender and sexuality in safety, they will continue to victimize LGBTQ people. Jesus called us to more — to a life of simple faithfulness, compassion, welcoming the stranger and putting the “other” above ourselves.

Over the past 50 years, no group has been more “othered” by churches than the LGBTQ community. It has to stop. Their lives may be hanging in the balance, and our gospel witness most definitely is.

Jason Koon is an ordained Baptist minister who writes at the intersection of faith and politics. He lives in Western North Carolina with his wife and two teenage daughters. His “Almost Ex-evangelical” blog is at www.jason-koon.com.

Related articles:

What do you say when a mom wishes her child were dead instead of gay? | Opinion by Bridget Eileen Rivera

Repressing my sexual orientation cost me my health — permanently | Opinion by Amber Cantorna

Baylor, ‘biblical sexuality’ and the good news | Opinion by Greg Garrett