Without meaning to do so, Henry Louis Gates’ two-part series on “The Black Church” dramatically exposed the gaping chasm that divides the way Black Christians and privileged white Christians — especially white evangelicals — understand God, protest and politics.

For many Blacks who follow Jesus, God is the God of justice who stands with marginalized people and turns the tables on those who carve out their wealth from the backs of the poor. The renowned Black theologian James Cone summed it up in a single phrase: Whatever else God may be, God is always “the God of the oppressed.”

Richard T. Hughes

From beginning to end, the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures bear this out.

When Austin Channing Brown was only 10 years old, she discovered “the God of the oppressed” in a Black Baptist church where “Jesus sounded like a Black person, dealing with familiar hardships of life — injustice, broken relationships, the pain of being called names.”

Not until she was an adult did she hear the name “James Cone” or read about Black Liberation Theology. “But by the time I learned of Black Jesus and his liberating power, I knew I had already met him at 10 years old, in a Baptist church where the Spirit moved us every week.”

Most white evangelicals, especially those who are steeped in privilege, find that language utterly baffling. For them, God has little or nothing to do with economic or racial justice in this world, but everything to do with one’s private walk with Jesus and salvation in the world to come.

There are many reasons for the white embrace of this severely truncated gospel, but one factor seems especially clear — the reality of American slavery that still casts its shadow over American religion and politics.

There are many reasons for the white embrace of this severely truncated gospel, but one factor seems especially clear — the reality of American slavery that still casts its shadow over American religion and politics.

Slave owners, though they may well have professed the Christian faith, never could acknowledge that the deity they worshipped was, in reality, “the God of the oppressed.”

While building their wealth on the backs of people they had enslaved, they never could acknowledge God’s concern with economic justice.

Nor could they rape, maim and lynch people with darker skin and acknowledge the biblical truth that God always sides with marginalized people against their oppressors.

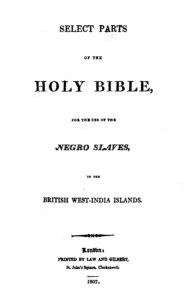

As a result, white evangelicals across the South transformed the Christian faith into a religion that was inward, private and otherworldly. With their focus on private talks with Jesus and salvation in the world to come, they could enslave human beings with consciences free from guilt.

“With their focus on private talks with Jesus and salvation in the world to come, they could enslave human beings with consciences free from guilt.”

In 1845, Frederick Douglass graphically described the brutal result: “The dealers in the bodies and souls of men erect their stand in the presence of the pulpit. The dealer gives his blood-stained gold to support the pulpit, and the pulpit, in return, covers his infernal business with the garb of Christianity.”

In the early- to mid-19th century, some evangelical Christians in Northern states led a frontal assault on slavery, but evangelicals in the American South, determined to resist that challenge, rooted their defense of slavery ever more firmly in their privatized, other-worldly version of the Christian religion.

Once slavery was abolished, that truncated version of the Christian faith slowly conquered the nation and helped create what we know today as “Christian America.” It legitimated Jim Crow segregation and silenced voices that might have spoken in protest against that system.

One might have thought that white Southern Christians would have heard in the message of the Freedom Movement of the 1950s and 1960s an echo of the biblical text and stood with Blacks in their struggle for justice. But they did not, and their calculated silence led Martin Luther King Jr. to wonder, “What kind of people worship here? Who is their God?”

The privatized, other-worldly piety of American evangelicalism still inspires silence in the face of injustice.

When the Trump administration, for example, separated children from their parents on the southern border and placed those children in cages, Attorney General Jeff Sessions, a devout evangelical Christian, marshaled the Bible to defend that practice and silence dissent. “I would cite to you,” he said, “the Apostle Paul and his clear and wise command in Romans 13 to obey the laws of the government because God has ordained the government for his purposes.”

“The privatized, other-worldly piety of American evangelicalism still inspires silence in the face of injustice.”

Sessions’ words fit a long, historic pattern. In the face of atrocities committed by their government against people of color — the Vietnam War, for example, or Jim Crow segregation, or voter suppression, or the crimes at America’s southern border — white evangelicals have typically run to the very passage cited by Attorney General Sessions to support their claim that Christians should obey the government, even if its policies are patently racist, unjust, oppressive and unfair.

They consistently take that position when government policies sustain their place of privilege in America’s social order. But when their privilege is threatened, all bets are off.

Televangelist Jim Bakker made that point crystal clear in 2017 when he claimed that, without Donald Trump, evangelical Christians would be “permanently shut up.” If Trump were impeached, he warned, Christians would “come out of the shadows” and “there will be a civil war in the United States of America.”

Suddenly, Romans 13 was irrelevant. Protest — even violent insurrection — was legitimate, enabled in part by the Jesus-and-me, otherworldly theology that is now so dominant in the United States of America.

White Christians clearly have much to learn from Black Christians about the meaning of their faith. To some small degree, the fate of the nation hangs on whether they are willing to open their hearts and take that crucial step.

Richard T. Hughes is the author of Myths America Lives By: White Supremacy and the Stories that Give Us Meaning, scholar in residence in the Center for Christianity and Scholarship at Lipscomb University, and a member of Public Theologians for Racial Justice.

Related articles:

Baptist Calvinists defend slavery of Southern Seminary founders

What Toni Morrison taught me about my people, the Quakers

‘Jezebel’ is one of three common racial slurs against all Black women and girls

‘While there is still time’: American churches, violence and conspiracy theories