Twenty-three years after John Piper called Doug Wilson an “absolute genius at sarcasm and irony,” pop Calvinists are still wringing their hands over how to respond to the conservative Reformed pastor from Moscow, Idaho.

“You’re very clever, really clever. And I think we need you like crazy,” Piper said of Wilson back then.

Referring to Wilson’s Credenda/Agenda publication, which was a conservative Reformed cultural and theological journal published from 1989 to 2012, Piper admitted, “I can O.D. on it fast because it is so well done from a rhetorical standpoint.”

As Al Mohler and R.C. Sproul sat quietly, Piper confessed he felt conflicted reading Credenda/Agenda because the magazine gave him a guilty pleasure — engaging his wiring “to be a person who puts down stupidity” while also making it “hard to manifest tenderness.”

Now the latest overflow of adulation and angst comes from Kevin DeYoung.

“I know a lot of good Christians who have been helped by Wilson,” he wrote. “Wilson is to be commended … deserves credit for being unafraid to take unpopular positions.” DeYoung went on to describe Wilson’s writing as “an angular, muscular, forthright Christianity in an age of compromise and defection.” He explained conservatives are attracted to Wilson’s “intellectual convictions because they were first attracted to the cultural aesthetic and the political posture that Wilson so skillfully embodies.”

Despite his fascination with Wilson, DeYoung attempts to put his finger on what he thinks is the real problem: Wilson’s “Moscow mood.”

No Quarter November

“For eleven months out of the year, I’m notoriously timid, as cautious and polite as a Southern Baptist raising funds for the ERLC,” Wilson states in the promotional video for what he calls No Quarter November. “But the month of November is a time for taking no prisoners and for granting no quarter. If you think of my blog as a shotgun, this is the month when I saw off all my typical careful qualifications and blast away with a double-barreled shorty.”

“Everything we do this month will be focused on one singular goal. We want to help you apocalypse-proof your family,” he proposes as his apron-wearing wife sets a turkey down in front of his plate.

For Wilson, making your family apocalypse proof means recognizing what is a violation against God’s royal decrees and then repenting without beating around the bush.

For Wilson, making your family apocalypse proof means recognizing what is a violation against God’s royal decrees and then repenting without beating around the bush.

“Like my parents taught me, a strong family isn’t possible without quick, full and honest confession of sin, without any wussy excuse making,” he asserts. “And especially now, it’s just as important not to confess and repent of things that aren’t really sins because lying is bad and so is being a wuss.”

After his turkey dinner is interrupted by a flashing red light and a perimeter breach alarm, Wilson gets up from the table, wields a blowtorch backpack to light a cigar, and then strolls out into the cold, blistery snowstorm to set ablaze cardboard cutouts of Disney characters and social media logos.

With everything from Elsa to the Instagram logo burning, the choice for conservative evangelical Calvinists seems to be between following Wilson’s culture war strategy of lighting cigars and burning cardboard in the snow while trying not to be a wuss or following DeYoung’s culture war strategy of toting “your brood of children through Target” because the “future belongs to the fecund.”

Both Wilson and DeYoung like to be on top

Of course, Wilson and DeYoung would claim to be promoting a theologically robust tower that stands much more firm and tall than the attention grabbing images they project.

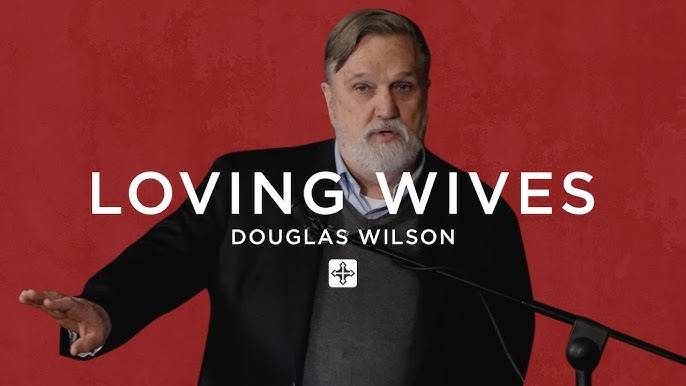

To Wilson, “a marriage is a little kingdom and the husband is a little king. Once married, he is the king of that little kingdom, and his decisions have real authority.”

Likewise, to DeYoung, “Patriarchy is inevitable. … What school or church or city center or rural hamlet is better off when fathers no longer rule? … The choice is not between patriarchy and enlightened democracy, but between patriarchy and anarchy.”

Their theology of patriarchal power in the home extends to their theology of power in society. In Wilson’s book Southern Slavery: As it Was, which was published four years prior to Piper calling him a genius, Wilson said: “Slavery as it existed in the South was not an adversarial relationship with pervasive racial animosity. Because of its dominantly patriarchal character, it was a relationship based upon mutual affection and confidence. There has never been a multi-racial society which has existed with such mutual intimacy and harmony in the history of the world. The credit for this must go to the predominance of Christianity.”

“We cannot understand the flourishing of Christendom unless we understand that it grew up out of the soil of warrior kings and barbarian kingdoms.”

DeYoung shares Wilson’s appreciation for Christian supremacy, even going so far as to make a positive case for the Crusades. In his critique of Wilson, DeYoung claims: “The Crusades expressed the best and the worst of this synthesis. There were times when the fusion of warrior-heroism and Christian virtue produced something noble and exemplary during the centuries-long effort to reclaim the Holy Land. And there were times when the fusion failed and produced something ugly and lamentable. But even the failures teach us about the aspirational ideals of Christendom. We cannot understand the rise of Western culture without the religious unity imposed by the Christian church in the Middle Ages, and likewise, we cannot understand the flourishing of Christendom unless we understand that it grew up out of the soil of warrior kings and barbarian kingdoms.”

DeYoung continues, “It looks as if Western culture has been overrun — whether by Muslim immigration in Europe, critical theory in our universities, sexual degradation in our popular culture, violence in our streets, or plain old anti-Western vitriol in the hearts of many Westerners who have no idea how much more miserable the world would be if their deluded wishes came true.”

In other words, both Wilson and DeYoung view the family and society as kingdoms of patriarchy where God rules by placing evangelical men as little kings at the top of the created order in a hierarchical system of authority and submission.

What is worldliness?

Both men share a concern that many who grow up in the kingdoms of fundamentalist patriarchy are familiar with being warned about — the pull toward “worldliness.”

DeYoung states: “I fear that much of the appeal of Moscow is an appeal to what is worldly in us. As we’ve seen, the mood is often irreverent, rebellious and full of devil-may-care playground taunts.”

But this is where Wilson leaves the script. “What is worldliness?” Wilson asks. “The thing that drives it is a deep desire for the world’s respect. Does Kevin really think that this is what I have been striving for? That I am trying to get the world to like me? To respect me? The only way people like me ever become respectable is after we’re dead and deep.”

He further clarifies: “If someone has an itch for respectability, that means that they have placed a huge steering wheel on their back, right between their shoulder blades, and the worldly wise are never hesitant to take the wheel.”

To DeYoung, worldliness would seem to be projecting an image of irreverent taunting. But to Wilson, worldliness is about giving up control to the world out of a desire to be respected by the world.

Worldliness in the context of hierarchy

Each of their definitions of worldliness fall short of how the Bible describes worldliness because you cannot talk about worldliness in a biblically literate way without examining how power is used to position certain people over others.

“The Bible was not written by a group of men at the top of society’s power dynamics.”

Of course, there are patriarchal dynamics and language in the Bible. The entire ancient Near Eastern and Greco-Roman cultures were based on hierarchies. But the Bible was not written by a group of men at the top of society’s power dynamics. Instead, the Bible was written by a group of oppressed people who were processing their exile and their oppression under the boot of empire.

It’s within that ancient sacralized hierarchy that Paul wrote to the Corinthians: “Consider your own call, brothers and sisters: not many of you were wise by human standards, not many were powerful, not many were of noble birth. But God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise; God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong; God chose what is low and despised in the world, things that are not, to abolish things that are.”

To Paul, worldliness wasn’t about one’s image or desire for respect, but about people and empires positioning themselves over others. To Paul, the work of God was the subversion of hierarchy. In today’s vernacular, one might call it the deconstruction of sacralized power. Therefore, the gospel subverts worldliness by revealing the throne as a Cross, the king as a slave, and by bringing to the Communion table people from all levels of hierarchy together in common equality.

Wilson and DeYoung are not subverting the power of empire by humbling themselves and promoting equality. Instead, they both are about sacralizing their own power by exalting themselves as little kings over their families and society.

Minimizing theology and focusing on mood

In one of the more puzzling moments of DeYoung’s article, he said his critique will not focus on historical or theological disagreements he “may have with Wilson.” Given his earlier partial affirmation of the Crusades, it seems odd he would refuse to clarify his theological differences on such topics as Federal Vision and Christian nationalism and would minimize the differences as “one or two conclusions that Christians may reach” regarding disagreements he “may” have with Wilson.

“I don’t think we can so easily divorce Wilson’s language from his theology.”

Instead, DeYoung said his “bigger concern is with the long-term spiritual effects of admiring and imitating the Moscow mood.” Calling Wilson’s promo video “just a little bit naughty,” DeYoung eventually worked his way around to criticizing Wilson rightly for using derogatory, dehumanizing language against women and LGBTQ people.

To be fair to DeYoung, I agree with confronting how Wilson dehumanizes people with his language, especially women and LGBTQ people. But unlike DeYoung, I don’t think we can so easily divorce Wilson’s language from his theology.

Distancing from Wilson to protect an image

“What I think is happening here is that a discussion is ongoing about how best to distance from me, but it can’t look as though it is happening because of heat from the left,” Wilson speculates. “Anthony Bradley has complained pointedly about how I have been platformed in the past by Desiring God, The Gospel Coalition, etc., which is true enough, but in order for them to not look like they are caving to pressure, the line has to be that I am the one who has changed.”

Wilson is correctly pointing out a pattern that has been going on in conservative pop Calvinism for decades.

In 1998, Mohler appeared on Larry King Live saying, “If you’re a slave, there’s a way to behave.” Then when asked if he would criticize the slaves who tried to escape, Mohler said, “I want to look at this text seriously, and it says to submit to the master. And I really don’t see any loophole here as much as, in terms of popular culture, we’d want to see one.”

Then after being pressured by those to his left in 2020, Mohler recanted his position, saying, “It sounds like an incredibly stupid moment, and it was. I fell into a trap I should have avoided, and I don’t stand by those comments. I repudiate the statements I made.”

But like DeYoung, Mohler didn’t offer any theological analysis why he was wrong. He simply gave into pressure and tried to move on.

Removing articles to protect an image

This year, when The Gospel Coalition came under fire over publishing and celebrating Josh Butler’s article sacralizing male sexual fantasies, they quickly removed the article and scapegoated Butler, despite privately continuing to promote Butler’s book in Amazon book reviews.

TGC pulled another article this year due to pushback after the writer was fantasizing about Taylor Swift. In this piece, the author wrote about Taylor Swift fans putting on shimmering dresses so that “through Swifties, the world saw Swift.” To TGC, this was a picture of Christians putting on Christ “to put his sparkling attributes on display to a watching world.”

“When Taylor was revealed, her appearance seemed flawless,” the author wrote. “I had high expectations, but when the petals came off, I wasn’t disappointed. Somehow, she was more beautiful than I imagined.” In the same way, the article said Taylor Swift’s beauty is a picture of Christ’s beauty.

Notice how little theology is being discussed. Instead, it’s all about image and appearances.

These men weren’t ignorant of Wilson’s theology when they platformed him because his writing was what drew them to promote him. Wilson has been the consistent one through these years, while the purveyors of pop Calvinism keep shrinking away and showing their timidity when people push back.

Pop Calvinism’s double-minded men

The “clever” Calvinists want to promote a sacralized hierarchy that “puts down stupidity” without using language that looks down on others. But their entire created order puts them at the top looking down at everyone below who is required to submit to them.

“They want to act like they’re theologically driven, and yet they’ll minimize and refuse to engage in theological conversation.”

The little warrior kings want to define worldliness as desire for the world’s respect, but then back down or block people who make them look foolish.

The online patriarchs think they can talk about the positives of the Crusades and the benefits of slavery or Christian nationalism without having to examine how the systemic harm those hierarchies created may have shaped society over time.

They want to act like they’re theologically driven, and yet they’ll minimize and refuse to engage in theological conversation. DeYoung said, “I’m not looking to get into a long, drawn-out debate with Wilson or his followers.” To which Wilson responded, “I am sorry that I need to explain this, but that is not how this works. You don’t get to launch a critique like this one, designed to make a lot of good-hearted people think twice about their attraction to the Moscow Mood, and then with a flourish refuse to take questions, or to be too busy for replies. You can’t launch an attack and then call for a cease fire.”

To be clear, Wilson’s theology and language are a monstrosity. And since Wilson already has named me among the pencil-necks and sob sisters this year, I’d imagine this piece will serve only to confirm his belief that those who criticize him tend “to be afflicted with an advanced case of rabies.”

But at least Wilson is consistently writing with the language of superiority that embodies the theology he espouses. The rest of the pop Calvinists who still can’t figure out how to respond to him after three decades are double-minded men, having divided loyalties between wanting to promote their own power over others while protecting their image when people call them out on the language of superiority their theology leads to.

Rick Pidcock

Rick Pidcock is a 2004 graduate of Bob Jones University, with a bachelor of arts degree in Bible. He’s a freelance writer based in South Carolina and a former Clemons Fellow with BNG. He completed a master of arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five children and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder. Follow his blog at www.rickpidcock.com.

Related articles:

Why these Christian men believe women shouldn’t have the right to vote | Analysis by Mallory Challis

Just what we needed: Another pompous declaration from the conservative Calvinist evangelicals | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

The threat of Christian nationalism has only grown since January 6 | Opinion by Brandan Robertson

We don’t need more ‘context’ to understand Josh Butler’s article on sex and the church | Analysis by Rick Pidcock