Six months after my mother had passed in 2011, I was at my sister’s house in Toronto, going through the relics of her life in her bedroom. While most people typically conjure an image of a cluttered, archaistic, clandestine room squandered away in some corner of the attic after a loved one passes, my mother’s room was spotless, nearly barren, save for the sweeping silk jacquard curtains that flanked either side of her bed in beige, and the ornate acrylic dresser she had gotten from Korea several decades before.

Glossed over in black and iridescent pearl illustration, the dresser was placed below a small, illuminated alcove in the wall, made specifically for a small vase or decorative pot. But instead of a pot or vase or embellishing statues and decor, she had placed there a wad of heavily saran-wrapped envelopes; enclosed within were various collections of photographs, some recent, some dating back from her early childhood. Yet on the back of each photograph always was a single set of digits: one palm-sized photo of her father, the only image she had of her father as a young man, had a single “50” written on the back in blue pen, and another picture of our first beautiful home in Korea had inscribed on the back, “#19.” Another image of me and my sister in the madang (outdoor courtyard in a Korean home) — I as a baby being held by my mother in white while my sister reached up and held her hand — had a “1” written on the back.

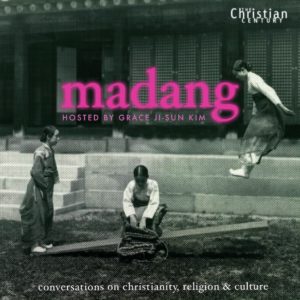

Grace Ji-Sun Kim

While my sister and I ended up keeping most of the pictures together at her home, I took those three photos back home with me, looking into them as if they would shift before me and reveal something new, or a memory undiscovered. But instead, I kept them in my Bible, something my mother did with a particular photograph of her father. From time to time, I take out the photos from their resting place and devour the images with my eyes again, before I swiftly flip them around and stare deep into a ravishing, ambiguous number.

I have thought over and over again of the significance of these numbers, most logically they should have been sequential with some form of linear timeline, except they were not. Perhaps she had simply labeled them in sequence of her most cherished photos, but there was no way she would have placed the image of our home over her beloved patriarch. Thus, there had to have been a third logical reason, one I have yet to unearth.

Some moments, when I see those numbers, one, 50 and 19, I think of her. I think of the way she guarded herself with her secrets and muffled privacy, always offering hints at the life she had lived before me, but never going into deeper explanation than a soft reminiscent sigh. I think of the way she would stiffen in sweeping rural land, like the farm she was raised on, feeling closed in by vast open space rather than liberated. But most often, I think of the open land as a giant question I had yet to find answers to, the stories I had yet to hear her tell — the life that gave life, which I had yet to inquire about while she still walked and breathed.

I keep this in mind through my work today, which aims to interrogate, enrich and bring us to a greater sense of understanding of this world we live in through the voices of writers, academics, activists, makers of social change, religious leaders and everyone in between. Through union and diverse conversation, I seek to leave no question unanswered, no idea unshared and no story untold. As the great Maya Angelou once said, “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.”

“I seek to leave no question unanswered, no idea unshared and no story untold.”

Thus, writing blogs, articles, books and now co-editing a book series, Asian Christianity in the Diaspora, I felt the next step would be to start a podcast to interview authors. I have been interviewed so many times for my books, I thought this would be the natural step in my book-loving world. Podcasts present a growing future of media consumption that cannot be ignored by our education systems and institutions. The format’s rise in popularity clearly coincides with a general increase in digital media consumption, specifically on mobile devices. I would like to engage in this increasingly more dominant medium and target the listeners who are curious about topics of religion, spirituality and culture who otherwise never would turn to traditional publications or journals (whether digital or print).

The methods in which people consume information have rapidly been redefined. In addition, the manner in which people educate themselves has rapidly been redefined. Easy access to free high-quality content for learning and entertainment has quickly shifted consumption patterns and expectations. We in academia have been slow to adopt emerging technologies to engage a dynamically changing audience. I hope to be a part of bringing some of the crucial discussions and subjects that are typically reserved for books, journals, online news articles and blog posts to accessible, audible content for a global audience.

I started my podcast in March 2021 with my first guest, Diana Butler Bass, on her new book, Freeing Jesus. Since then, I have had other prominent guests such as Jesse Jackson, Russell Jeung and Al Sharpton and will have future guests such as Kristin Du Mez, John Nichols, Jacqui Lewis and Chris Hedges. Since May, Madang podcast is now hosted by The Christian Century magazine. The art of interviewing is one fun aspect. Editing, producing and finding sponsors is another aspect.

I chose to call my podcast “Madang,” a Korean word that refers to the outdoor courtyard. A traditional characteristic of a Korean home, the madang is like an outdoor family room where friends and strangers alike gather to engage in conversation, debate and celebration.

I chose to call my podcast “Madang,” a Korean word that refers to the outdoor courtyard. A traditional characteristic of a Korean home, the madang is like an outdoor family room where friends and strangers alike gather to engage in conversation, debate and celebration.

My fondest memories of my childhood in Korea were when I would visit my grandmother’s house. There, dropped like a patch of vibrant green earth in moldy concrete, was the madang. It was the place in which I played make-believe, the place where real life and the abstract first met.

Most of the rooms in the home are entered through the madang, and thus it serves as a space for encounter and sharing, celebration and fellowship, greeting a visitor and welcoming a stranger. Ancient, medieval and even contemporary European buildings are built on the same principle. Perhaps the madang is something like the courtyard at the Cloisters in New York City, although the surrounding building there is far larger than what my grandmother had or what most Korean homes would have. My grandmother’s home was small, with just two rooms leading away from the madang.

My hope with the Madang podcast is to establish a network of virtual madangs, welcoming an array of guests to freely talk about their life, their understandings of God and their opinions on modern issues in religion and culture. It is my hope that listeners will create madangs around the world as they listen in, sharing the madang space we all cohabit to incite greater compassion, humanity and justice in the world.

The madang is open: I invite you to come in, converse, envision, reimagine and stay for a while.

Grace Ji-Sun Kim is professor of theology at Earlham School of Religion in Richmond, Ind., and earned a Ph.D. from the University of Toronto. She is an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church (USA) and the author or editor of 20 books.

Related articles:

Dallas pastor pitches ‘Good God’ podcast toward the common good

What I learned from spending three days with the ‘Duck Dynasty’ family

They grew up in purity culture, then taught it and now want to help others recover from it