Our nation lives in suspended grief over 900,000 dead from COVID. Every day we go to the funeral home, the graveyard. Every day the bells toll for those who keep dying from COVID. Where are words of comfort? Is there a balm in Gilead?

Our nation is suspended in the darkness of grief between denial and anger. Thomas G. Long, in Accompany Them with Singing: The Christian Funeral, suggests that we are caught in an upheaval in the ways we care (or don’t) care for the dead “that are inevitable signs of an upheaval in the ways we care (or don’t) for the living.” He laments our loss of the practice of honoring the dead in a distinctive Christian manner.

After 9/11, as the nation mourned, we learned how secular we had become, when the nation turned to the “church of baseball” to honor the dead and justify a war on terrorism. Tributes at baseball parks across the country offered comfort to a shocked and grief-stricken nation.

This secular response wrapped itself in the singing of God Bless America, but the comfort wasn’t Christian. In fact, as Michael L. Butterworth argues, the comfort discouraged the expression of dissenting opinion. Butterworth puts it succinctly: “This essay views the aftermath of 9/11 as a quasi-religious social drama in which ballpark tributes became a ritualized vehicle for a belligerent patriotism that sought unity at the expense of democratic discourse.”

In ways small and large, we are still trapped in the grief of 9/11. America has become church, in Stanley Hauerwas language, and war our national liturgy.

“In ways small and large, we are still trapped in the grief of 9/11. America has become church, in Stanley Hauerwas language, and war our national liturgy.”

Now we have COVID and the dead pile up in a metaphor borrowed from Ezekiel 37: “A valley full of bones — they were very many lying in the valley, and they were very dry.” And still we grieve. There are outbursts from time to time, but they are outbursts of anger and violence. They are not consoling to the soul of America.

Words of transformation

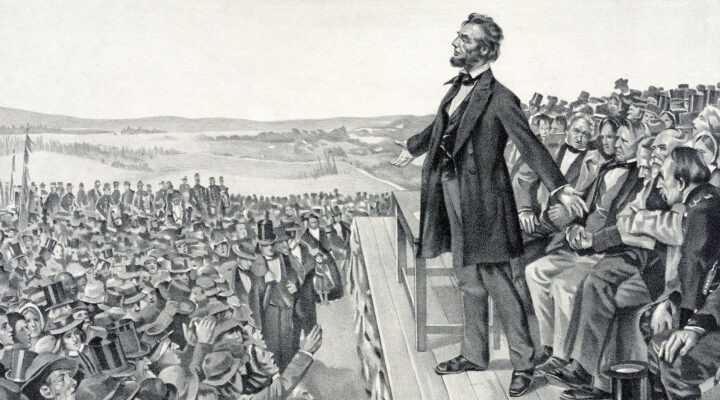

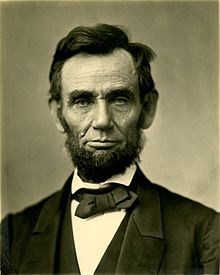

Is it time for another Gettysburg Address? Are there words of transformation from Lincoln still possessing the power to save us from our choked-off grief now gushing forth from the bowels of our lesser angels as resentment, destruction, hatred and violence?

Perhaps Lincoln can again remind us of how to offer the funeral eulogy for all the people. Here is the American prophet’s eulogy for the nation and her dead at Gettysburg:

Perhaps Lincoln can again remind us of how to offer the funeral eulogy for all the people. Here is the American prophet’s eulogy for the nation and her dead at Gettysburg:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, upon this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation, so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met here on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of it as a final resting place of for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. But in a larger sense we cannot dedicate — we cannot consecrate — we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here, but can never forget what they did here. It is for us, the living, rather to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they have, thus far, so nobly carried on. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to the that cause for which they here gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation shall have a new birth of freedom; and that this government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Consumed by an age of simplicity

Lincoln addresses the ages. Our politicians are so media-savvy, so news-cycle imprisoned, so instant, so immediate that there is no sense of connection to past or future. Instead of embracing history, some of our leaders are attempting to deny, denigrate, cover up and divorce from American history. Others read polls, hold rallies, rip up historical documents, fill the world of Twitter with “nothing,” and pose and posture with quips and vicious attacks that have nothing to do with our history as a deliberative democracy.

Brian L. Ott and Greg Dickinson, in The Twitter Presidency, point out that we are consumed by an age of simplicity, impulsivity and incivility. This is fertile ground for rage, anger and denial. Is this where we are as a nation — trapped in between two of the stages of grief?

“We are consumed by an age of simplicity, impulsivity and incivility.”

Rhetorical scholar Edwin Black says that Lincoln “speaks the voice of omniscience, articulating a historical narrative with incontestable certitude. The first paragraph is a description of national genesis. It is a purposeful creation, an initiating fusion of origin and essence: the generation not only of an entity, but also of a mission.”

Black notes that “Lincoln states who we are as a nation and a people. Anyone who would deny, doubt or qualify the narrative is implicitly excluded from Lincoln’s audience.” Lincoln’s opening paragraph speaks the deep spirituality of this president. The words feel at one with “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.” Now, our political leaders, like flat-earthers, intelligent designers and literal creationists, fight like cats and dogs over the meaning, mission and nature of our democracy.

Who could give this address today?

Our politicians would struggle to persuade us that we have a responsibility to the 900,000 people dead of COVID. Many Americans are unwilling to be held accountable for anything — past or present. Lincoln pulled his audience into the fray with the phrase, “us the living.” With the instruction to “us the living” there is a stark reality that “we” stand in deputy to the whole nation and act on its behalf.

Lincoln sounds here like the mystical writer of Hebrews 11: “Yet all these, though they were commended for their faith, did not receive what was promised, since God had provided something better so that they would not, apart from us, be made perfect.” Nine hundred thousand Americans wait in suspension for us to honor them, release them and do what is good and decent and honorable.

Yet, politicians are not “deputy to” the nation, only to partisan selfishness. Politicians feel privileged. It is rare to hear a U.S. senator say what Lisa Murkowski says: “I’m not here to be the representative of the Republican Party. I’m here to be the representative for Alaskan people. And I take that charge very, very seriously. So, when there is a conflict, when the party is taking an approach or saying things that I think are just absolutely wrong, I think it’s my responsibility, as an Alaskan senator speaking out for Alaskans, to just speak the truth.”

Those are words indispensable for the birth of a new Gettysburg-like address.

Senatorial candidate J.D. Vance, right, and Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene, left, pose for a photograph with a supporter in Mason, Ohio, Sunday, Jan. 30, 2022. (AP Photo/Jeff Dean)

The “nation” — named five times in the Gettysburg Address — represents a permanent and fixed reality. The nation, the nation, the nation — more essential than any political party or movement. Even with the nation ripped apart by civil war, Lincoln insists on maintaining the deep reality of the “nation.”

I have trouble hearing this tune of the nation in our current batch of politicians. My mind struggles to imagine Marjorie Taylor Greene or Mat Gaetz having the ability to make an address that would allow the nation to mourn 900,000 dead from COVID. I have even more difficulty imagining the Senate’s resident quipster, John Kennedy, pulling off such rhetorical excellence. Politics reduced to a quip a day, five tweets a day, an attack on others a day, and no policy, no vision, no deliberations of substance will not long sustain our democracy.

Democracy has no place for silliness

The courts of kings long survived with the entertainment provided by rhapsodes, raconteurs, fools, clowns and jesters. The court of democracy has no lasting place for this sort of silliness. It is temporary, fleeting, instantaneous, laughable and, at the end, destructive.

Someone has to govern at some point. Where are the people capable of the intellectual breadth of Patrick Moynihan: “I’m of a generation which I don’t think will be reproduced for a while” he said, “which is deeply respectful of American government and owes so much to it.”

“We have spoiled children running the show in Congress and they demand constant attention.”

Now, we have spoiled children running the show in Congress and they demand constant attention. They come out each day to play and will say anything to get attention, approval and approbation from an addled public. Instead of reading The Art of War, these politicians should be required to read and take an examination on Everything I Needed to Know I Learned in Kindergarten.

Words of Jesus float to conscious thought when I hear statements from our elected officials: “But to what will I compare this generation? It is like children sitting in the marketplaces and calling to one another, ‘We played the flute for you, and you did not dance; we wailed, and you did not mourn.’”

Our nation lives in an extended time of suspended grief.

Should we scream or sing?

American historian David Blight questions whether we should scream or sing. I suggest we accompany our dead with singing and that we allow the magnificent poet of democracy — Walt Whitman — to direct our national choir: “We thought our Union grand and our Constitution grand; I do not say that they are not grand and good — for they are. I am this day just as much in love with them as you, but I am eternally in love with you and with all my fellows upon the earth.”

Or there’s Whitman’s definition of democracy: “I speak the pass-word primeval; I give the sign of democracy/ By God! / I will accept nothing which all cannot have their counterpart of on the same terms.”

How did we manage to lose our sense of a universal community without damaging division, our us without a them? Now we have a rhetoric that hurts democracy, a rhetoric designed to demolish rather than build. Republicans in general, and some Democrats, have a dualist view of the world — either/or, but they have a duelist view of politics — “pistols at dawn.”

Whitman excludes no one. In his “Poem to a Common Prostitute,” he says, “Not until the sun excludes you do I exclude you.” There’s an equalizing virtue in Whitman now lost in those who play political games for political gain at the polls, in redistricting efforts and voter suppression. Where are the politicians willing to draw together the entire cast of motley characters: the high level with the low, rich with poor, men with women, white with Black, North with South, East with West? This is the glory of America, but instead of ontic wonder and existential gladness, our politicians weaponize words to deprive others of rights.

Taking responsibility for the dead

In the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln offers us the same kind of democratic spirituality. He delivers the moral ultimatum. He calls forth the people to take responsibility for completing the mission of the dead.

Jeremy David Engels writes: “Our past has led us to the point of declaring this burial ground sacred; but yet, we demur. Why? Because we have neither the right nor the duty. A moral intervention prevents the fulfillment of conventional form; a customary itinerary has been deflected. Our right has been superseded by those who have died. Our duty lies elsewhere: it is to take up the task left unfinished by the dead. The speech links us to the dead by virtue of the common task, and by the bond of our obligation to complete what they have left incomplete.”

“We cannot go on as a people until we mourn our dead.”

We cannot go on as a people until we mourn our dead. The “art of living” will dissolve into fractious fascism otherwise. The “care of the self” will disintegrate into the rhetorical perversion of advertising that will sell us pleasure but never gratefulness, goods but never the good.

A road to demolition

The path we have taken is not a path of goodness, gratitude or unity. The mocking, scoffing, scorning political rhetoric, so revered by many, will lead only to demolition.

As the writer of Proverbs reminds those who follow such rhetorical deceptions, they will be like he who “goes like an ox to the slaughter or bounds like a stag toward the trap until an arrow pierces its entrails. He is like a bird rushing into a snare, not knowing that it will cost him his life.”

We can avoid this only if we can return to talk of the good which is foundational for democratic politics. In the Phaedrus, Plato argues that only by invoking the good will we survive those moments when truth alone is not enough to persuade.

The Gettysburg Address, always considered one of the finest rhetorical achievements of our political speech-making, seems far removed from our current fascination with the superficial, the temporary, the humbug. Politicians weaponize words to hurt, criticize and accuse others. There’s nothing of Lincoln in today’s political speeches, especially not from his own party. President Trump, still the voice and embodiment of the Republican Party, is the anti-Lincoln. His tongue would split open trying to use the words of Lincoln.

Who will volunteer?

The time has come to ask the serious questions of David Blight: “Who on the left will volunteer to be part of a delegation to go discuss the fate of democracy with Mitch McConnell, Kevin McCarthy or the foghorns of Fox News? Who on the right will come to a symposium with 10 of the finest writers on democracy, its history and its philosophy, and help create a blueprint for American renewal?”

Gettysburg

He answers his own questions with these words: “As a culture we are not in the mood for such reason and comity.”

Thomas Farrell, in Norms of Rhetorical Culture exhorts, “Democracy demands that people, talk, laugh, argue, sing and deliberate not only with their friends but also with strangers.” Farrell’s enthusiasm reminds me of the bard of democracy, Walt Whitman, who insisted that democracy take place in diverse sites: street corner, local pub, produce market, feed store, coffee shop, a park, a living room, a board room.

These are democracy’s temples, synagogues, ashrams. Herein is our national release from grief.

Perhaps only a Lincoln can save us now.

Rodney Kennedy

Rodney W. Kennedy currently serves as interim pastor of Emmanuel Freiden Federated Church in Schenectady, N.Y., and as preaching instructor Palmer Theological Seminary. He is the author of nine books, including the newly released The Immaculate Mistake, about how evangelical Christians gave birth to Donald Trump.

Related articles:

Lincoln’s religious influence in forging Emancipation Proclamation still evident after 150 years

What Abe Lincoln tells us about Trump, Biden, guns, God and Falwell Jr. | Opinion by Bill Leonard

Abraham Lincoln, Susan B. Anthony and Adam Sandler: Signs of a church that is more than a museum | Opinion by Brett Younger