The phrase “antithetical to the gospel” has become a favorite way to shut down ideas with which Christians disagree. Don’t like someone else’s theology or politics or social views? Just declare those views “antithetical to the gospel,” and that’s that.

When Southern Baptist Convention apologist Al Mohler wanted to explain why he opposes Critical Race Theory, he said this: “The main consequence of Critical Race Theory and intersectionality is identity politics, and identity politics can only rightly be described as antithetical to the gospel of Jesus Christ. We have to see identity politics as disastrous for the culture and nothing less than devastating for the church of the Lord Jesus Christ.”

Likewise, when the SBC seminary presidents in late November 2020 issued their declaration against Critical Race Theory, the Baptist Press story that quoted each of the presidents used the word “gospel” nine times.

“As this statement demonstrates, our convention leaders affirm without reservation not only our historic Baptist theological confessions, but also a biblical view of justice, which I also affirm and applaud,” then SBC President J.D. Greear said. “While we lament the painful legacy that racism and discrimination have left in our country and remain committed to fighting it in every form, we also declare that ideological frameworks like Critical Race Theory are incompatible with the BFM. The gospel gives a better answer.”

When it may be hard to label something as antithetical to the gospel, it is called antithetical to the Baptist Faith and Message.

In this statement, Greear illustrates a subtle shift that he and others — especially the seminary presidents — have made to use the Baptist Faith and Message doctrinal statement as a stand-in for “the gospel.” When it may be hard to label something as antithetical to the gospel, it is called antithetical to the Baptist Faith and Message.

Popularized by the Reformed movement

The “antithetical” language is especially prevalent among the young Calvinists of the SBC and other nondenominational Reformed movements. The Gospel Coalition, for example, takes its very name from a defense of what it believes is the essential essence of the gospel.

This summer, when a group of mainly Reformed young conservatives held a conference in Denton, Texas, to refute what they believe is the errant theology of “wokeness,” they titled their event the “Wokeness and the Gospel Conference.”

A Facebook promotion for this event explained: “Scripture speaks about who we are and what our greatest problem is. The culture also has something to say about who we are and what our greatest problem is. At the Wokeness and the Gospel Conference, we are going to equip ourselves to understand what Scripture says so we will not be taken captive by what the world is saying. We will also address why what the culture says is antithetical to the gospel of Jesus Christ.”

“Let’s be clear: none of this is biblical, in fact it is all antithetical to the gospel.”

The Gospel Project, an online curriculum produced by Lifeway, promotes its product this way: “We love to find ways to separate ourselves as people. We are so good at finding reasons, almost all of which are pretty poor and many even sinful, to divide ourselves. We relish an ‘us against them’ posture, one which is manifested in countless forms of ‘us’ and ‘them.’ Let’s be clear: none of this is biblical, in fact it is all antithetical to the gospel.”

A defense mechanism for progressives too

But it’s not just conservatives and Calvinists adopting this phrase as their shield of defense. It crops up from time to time among progressives, too.

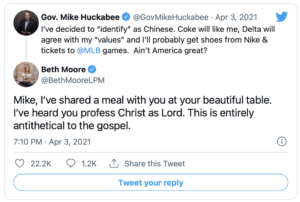

In April, former Arkansas governor and Baptist pastor Mike Huckabee tweeted an anti-woke thought: “I’ve decided to ‘identify’ as Chinese. Coke will like me, Delta will agree with my ‘values’ and I’ll probably get shoes from Nike & tickets to @MLB games. Ain’t America great?”

In April, former Arkansas governor and Baptist pastor Mike Huckabee tweeted an anti-woke thought: “I’ve decided to ‘identify’ as Chinese. Coke will like me, Delta will agree with my ‘values’ and I’ll probably get shoes from Nike & tickets to @MLB games. Ain’t America great?”

His tweet was condemned as racist and labeled by some Asian Americans as hate speech. The New Georgia Project, a voting rights group based in Georgia, called the tweet “openly racist,” and Bible study leader Beth Moore — who famously quit the SBC recently — called Huckabee’s tweet “antithetical to the gospel.”

Anthony Parrott, lead pastor of The Table Church in Washington, D.C., employed the same language to note what’s wrong with the death penalty in America: “Capital punishment is antithetical to the gospel of Jesus. You cannot simultaneously believe that God is the God of redemption, forgiveness and transformation and believe that the best response to certain kinds of crime is execution.”

And the Duke Divinity School-affiliated newsletter Faith and Leadership reported an interview with author Dominique D. Gilliard also opposing capital punishment: “In his new book, Rethinking Incarceration: Advocating for Justice That Restores, Gilliard examines the history of mass incarceration in America and Christianity’s role in its evolution and expansion. It’s a phenomenon that is antithetical to the gospel, he said.”

Gilliard made the same kind of argument — but from the opposite vantage — that conservatives have made about the nature of the gospel: “Christians have to understand that we can’t buy into the same meritocratic way of thinking and being as the rest of the world does. We know that we are sinners saved by grace. And that grace that allows us to be reconciled to God and to one another marks how we respond to crime and violence in the world.”

Among the many things conservatives and progressives cannot agree on in America today is the very definition of the word “gospel.”

Among the many things conservatives and progressives cannot agree on in America today is the very definition of the word “gospel.”

What is ‘the gospel’?

The Greek word for “gospel” that made its way into the New Testament is euangelion, sometimes also transliterated as evangelon, which simply means “good news.”

Thus, “the gospel” is not a reference to the four Gospels, which are the first four books of the New Testament that tell the story of Jesus’ birth, ministry, death and resurrection. The Gospels contain gospel but are not the sum of “the gospel.”

The lay-friendly website The Bible Project notes that the word “gospel” may mean different things to different Christians: “In Christian communities, the word ‘gospel’ is often used as a shorthand for the core message of the Christian faith. However, the exact meaning of gospel varies from church to church, based on the larger tradition or denomination. For some, ‘gospel’ refers to the message that Jesus died for the sins of humanity. For others, it may refer to the general idea that God loves us or that we will spend eternity with him.”

Nor is euangelion a uniquely Christian word in its origin. Some biblical scholars point to a well-documented use of the word in praise of Caesar Augustus in what is known as the Priene Inscription, dating to about 9 B.C.

The Priene Inscription includes these lines: “Since Providence … has set in most perfect order by giving us Augustus, whom she filled with virtue that he might benefit humankind, sending him as a savior, both for us and for our descendants, that he might end war and arrange all things, and since he, Caesar (and inherent from this Lord), by his appearance … surpassing all previous benefactors, and not even leaving to posterity any hope of surpassing what he has done, and since the birthday of the god Augustus was the beginning of the good tidingsfor the world that came by reason of him … .”

This is the context in which Jesus appears and declares a different kind of gospel.

Thus, in the Roman Empire, the rule of a Caesar was declared “good news” for the people. This is the context in which Jesus appears and declares a different kind of gospel. The word also appears in the writings of Homer, Cicero and Plutarch.

‘Good news’ in the New Testament

The word euangelion appears 77 times in the Greek New Testament, from Matthew to Philemon. It appears in some well-known passages, such as Matthew 4:23 — “And he went throughout all Galilee, teaching in their synagogues and proclaiming the gospel of the kingdom and healing every disease and every affliction among the people.”

Or Matthew 24:14 — “And this gospel of the kingdom will be proclaimed throughout the whole world as a testimony to all nations, and then the end will come.”

Mark uses this word in the first verse of his Gospel, which he says tells “the beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God.”

The Apostle John is arrested for proclaiming the gospel. The Apostle Paul gives himself devotedly to spreading the gospel. The gospel is said to bring strength to the church at Rome. Paul contends against the preaching of a false gospel in Corinth and Galatia. And to the church at Ephesus, the gospel is described as “a mystery” that must be revealed.

Dueling definitions

How, then, have we come to a point in modernity where “the gospel” seems to mean not only different things but sometimes opposing things?

How, then, have we come to a point in modernity where “the gospel” seems to mean not only different things but sometimes opposing things?

The Gospel Coalition — the conservative evangelical Reformed network — includes a section defining the gospel in its confessional statement.

“We believe that the gospel is the good news of Jesus Christ — God’s very wisdom. Utter folly to the world, even though it is the power of God to those who are being saved, this good news is christological, centering on the cross and resurrection: the gospel is not proclaimed if Christ is not proclaimed, and the authentic Christ has not been proclaimed if his death and resurrection are not central.”

Among its other descriptions of “the gospel,” The Gospel Coalition does not list a call to action or advocacy.

On the other hand, the progressive Christian group Red Letter Christians outlines a different perspective on its gospel mandate without using the exact word “gospel.”

“The goal of Red Letter Christians is simple: To take Jesus seriously by endeavoring to live out his radical, counter-cultural teachings as set forth in Scripture, and especially embracing the lifestyle prescribed in the Sermon on the Mount,” the group’s website explains. “By calling ourselves Red Letter Christians, we refer to the fact that in many Bibles the words of Jesus are printed in red. We, therefore, assert that we are committed first and foremost to doing what Jesus said. Jesus calls us away from the consumerist values that dominate contemporary America. Instead, he calls us to meet the needs of the poor. He also calls us to be merciful, which has strong implications in terms of war and capital punishment. After all, when Jesus tells us to love our enemies, he probably means we shouldn’t kill them.”

“Biblical justice is the manifestation of the full gospel of Christ.”

The Red Letter Christian website offers multiple interpretations of its definition of “the gospel” as it addresses specific current events. In one, for example, writer Mae Elise Cannon writes: “I’ve become increasingly convinced that the gospel of Christ cannot be fully expressed without both salvation and justice being integrated and pursued. Biblical justice is the manifestation of the full gospel of Christ.”

The Gospel Coalition and Red Letter Christians exemplify two sides of the modern debate over the meaning of the word “gospel,” which in turn influences what is perceived to be “antithetical” to it. On the one hand, the gospel is adherence to a specific set of doctrines; on the other hand it is adherence to a specific set of actions.

Defining ‘gospel’ more broadly

Dale Martin, Woolsey Professor of Religious Studies at Yale University and a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, addresses the meaning of the gospel in his book Biblical Truths.

Dale Martin

“I take ‘gospel’ to refer to whatever linguistic entity is taken to encapsulate the good news that God provides for human beings through actions, faith and faithfulness of Jesus Christ,” he writes. “In my usage, ‘gospel’ corresponds to what theologians, especially those influenced by modern German scholarship, have called the kerygma: the preached message that promises salvation and converts human beings to faith in God through Jesus Christ. The specific wording of these ‘kernel’ messages can never be finalized into an invariable formula. It is the ‘saving message’ of what God has wrought for us through Jesus Christ, and the Holy Spirit uses that message to inspire faith in us.”

Martin cites the work of James Alison, who named three creedal-like examples of this “kernel” from the New Testament: John 3:16; Romans 3:22-25, and 1 John 4:9-10.

The first, of course, is the most well-known verse in the Bible, telling of God’s love for the whole world. The second tells of humanity’s sinfulness and God’s grace, including this well-known line: “for all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God and are justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus.” The third tells of God’s love through Jesus Christ: “In this the love of God was made manifest among us, that God sent his only Son into the world, so that we might live through him. In this is love, not that we have loved God but that he loved us and sent his Son to be the propitiation for our sins.”

Then Martin adds his own fourth example, 2 Corinthians 5:19, which is about God’s message of reconciliation: “In Christ God was reconciling the world to himself, not counting their trespasses against them, and entrusting to us the message of reconciliation.”

This short kerygma echoes the teaching of the early church, which was not based on memorizing or affirming specific Scriptures that had not yet been written down.

This short kerygma echoes the teaching of the early church, which was not based on memorizing or affirming specific Scriptures that had not yet been written down.

From an early church perspective, “the gospel” also would have been seen as apocalyptic. The message had urgency because of the imminent return of Jesus and the way that belief urgently reordered life’s priorities. To believe the gospel meant changing the way one lived — a set of actions driven by belief.

A third way

In a sense, both the right and the left may get the definition wrong for “the gospel,” according to Little Rock, Ark., pastor Matt Dodrill, a graduate of Duke Divinity School.

Matt Dodrill

The gospel, he says is “the good news of God’s rectifying act in Jesus Christ. It’s not the good news of my attempts to usher in the kingdom through social justice or some such thing. That’s not to say that social justice isn’t important. I just mean that my attempts to rectify the world and implement justice are impotent and vulnerable to being co-opted by powers and principalities.”

Justice, he says, “comes through Jesus Christ alone, and I’m invited by grace to participate in that reality. Put differently, the gospel should always be presented as an indicative: ‘In Christ, God is reconciling the world to himself.’ If I become an ambassador of reconciliation, I do so in response. But the response, in and of itself, is not the gospel.”

That’s the peril for progressive Christians, he says, who “tend to put all their emphasis on the imperative of justice, making human action their point of departure. … That’s where the phrase ‘antithetical to the gospel’ would be apt, in my opinion. Humans are not the primary agent of justice. God is. I prefer to say that the imperatives of doing justice, loving kindness and walking humbly with God rise organically from the indicative of grace, such that we can embody the gospel as God works through us.”

“If God is not the subject of the sentence (the one doing the action), that sentence is not the gospel.”

Or more simply: “This is a just long way of saying that if God is not the subject of the sentence (the one doing the action), that sentence is not the gospel.”

On the other hand, making “the gospel” only about precepts and doctrines carries its own dangers, Dodrill added.

Yes, doctrine matters: “If I say, ‘Jesus died on the cross but was never raised from the dead,’ that statement is antithetical to the gospel in terms of its sheer content.”

However, even the basic Christian affirmation that “Jesus is Lord” can misrepresent the gospel if applied in ways that defy the lordship of Christ — that are, in essence, antithetical to the gospel.

Dodrill quotes theologian George Lindbeck in The Nature of Doctrine: “For the Christian, ‘God is Three and One,’ or ‘Christ is Lord’ are true only as parts of a total pattern of speaking, thinking, feeling and acting. They are false when their use in any given instance is inconsistent with what the pattern as a whole affirms of God’s being and will.”

Screenshot of a scene from the U.S. Capitol riots on Jan. 6, 2021.

For example, Lindbeck cites the crusader’s cry, “Christus est Dominus” as false when used to authorize the murder of a perceived infidel. Even though “Christ is Lord” is a true statement for the Christian, it is not true in connection with such an antithetical act.

“When thus employed, it contradicts the Christian understanding of lordship as embodying, for example, suffering servanthood,” Lindbeck writes.

And for a modern-day example of such an antithesis, look no further than the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, Dodrill says, noting how the vengeful crowd carried Christian flags, used Christian language and waved a flag declaring “Jesus is Lord.”

“Right there’s a contemporary example of the antithesis of the gospel,” he says.

Related articles:

Six ways ‘American Gospel’ is small-minded and abusive | Analysis by Rick Pidcock

Is our gospel no longer the gospel of the early church? | Opinion by Bill Rosser

Bonhoeffer moment No. 1: Claiming Christ but losing the gospel | Opinion by Bill Leonard