Republican officials, partnered with the Aitken Bible Historical Foundation and the First American Bible Project, are lobbying to have editions of the Aitken Bible provided for use in public school classrooms. The initiative has been especially popular in Tennessee, but already has provided about 2,500 Bibles to 750 public schools across 11 states.

What is the Aitken Bible?

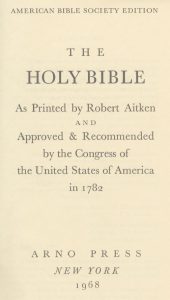

The text is not a widely used translation of the Bible. In the shadows of translations such as the ESV, NIV, NRSVUE, and KJV, the Aitken Bible is unfamiliar to most practicing Christians, conservative and liberal alike. However, proponents of the text’s use in schools argue it is an important object of American Christian history.

The 1,452-page Aitken Bible is a 1782 translation of the biblical text produced by Philadelphia printer Robert Aitken. It was the first American-printed translation of the Bible, and unlike most Bible translations that are formulated for linguistic or spiritual purposes, it was created with political intentions.

In response to a trade embargo affecting the importation of books from Britain, the ability to print and distribute the text in America served as a symbol of the United States’ independence.

In response to a trade embargo affecting the importation of books from Britain, the ability to print and distribute the text in America served as a symbol of the United States’ independence.

Given this, there is little historical emphasis on the religious or spiritual importance of the text for Americans. The text seems to have functioned in an ideological manner for the country in the “marketing of a new American identity.”

Rather than an endorsement of Christian faith, American Revolution expert Tad Stoermer told The Tennessean, the Aitken Bible symbolized the country’s ability to function independently from Britain as a new nation.

The Aitken Bible symbolized the country’s ability to function independently from Britain as a new nation.

In fact, it seems the text was not very popular beyond its symbolic role. Historians note Aitken did not make much profit from Bible sales, and he went into serious debt due to lack of sales. Once the embargo was lifted, Americans continued purchasing British Bibles again, which were higher in quality.

Throughout history, however, the text has been referenced in arguments supporting a particularly Christian identity for Americans. Notably, this is due to its endorsement by the Continental Congress. However, historians again emphasize the political context.

Library of Congress Librarian Marianna Stell, who has worked with the Rare Book and Special Collections Division since 2017, says the endorsement was not one of spiritual belief among the Founding Fathers. Instead, it aimed to emphasize “the country’s burgeoning cultural identity detached from that of Britain’s,” especially in the face of the embargo.

So, while the Bible itself is a devotional text, the production of the Aitken Bible was a patriotic venture for the emerging country, not necessarily a spiritual one.

The First Amendment ‘myth’

Despite this historical context informing the meaning of the text, supporters of the Aitken Bible’s use in public schools today see the text as evidence that the separation of church and state does not apply to Christianity. For example, the Wallbuilders organization does this in their arguments to expose what they call the “myth of separation of church and state.”

ThomasJefferson

One central point of their argument is the absence of the particular phrase “separation of church and state” within the First Amendment.

The phrase made its inception in an 1801 letter from Thomas Jefferson to concerned Baptists in Connecticut who wanted clarification on what protections religious folks in America had to freely practice their beliefs. He explained there was a “wall of separation between church and state” that prevented the government from establishing a state-sanctioned religion but ensured private citizens the right to freely exercise faith.

Conversations about the government’s neutrality on religion were reiterated later, such as in the 1947 Supreme Court case Everson v. Board of Education, when the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled public school dollars could be used to pay for private school transportation costs, most of which were Catholic. In this case, the Supreme Court cited the First Amendment’s prohibition for Congress against making laws establishing any particular religion as the means through which U.S. law separates the forces of church and state, but upheld the freedom of individual states to make these decisions for their schools.

Wallbuilders, however, interprets the 1947 invocation of this language as extreme and inaccurate, arguing that church and state are not separate. The organization instead favors an interpretation of American history in which the Christian God, not the government, dictates rights and liberties for citizens.

This, they argue, is evidenced by Congress’ endorsement of the Aitken Bible as a symbol of Christianity as an essential aspect of American identity, despite historians’ advice that this interpretation of the Bible’s role in U.S. history is incorrect.

The Bible as an American historical resource

Current debates on the Bible’s use in schools center the efforts of Stephen Skelton, founder of the Aitken Bible Historical Foundation and the First American Bible Project. Skelton told The Tennessean his work aims to provide copies of the Aitken Bible as a historical resource to aid teachers when discussing “topics they’re already teaching about,” such as the “economic factors of the American Revolution.”

Robert Aitken

The same article notes that, while his official stance regarding his corporate endorsement of the Aitken Bible’s use in schools centers his understanding of its historical importance, Skelton has expressed personal skepticism surrounding separation of church and state in the U.S. and has “pointed to the Aitken Bible to back up his views.”

And while it is true the text’s translation and publication may be used as an example of the particular moment in U.S. history, experts and historians warn against a view of history that overly emphasizes the text’s religious influence.

They say it perpetuates the misconception that the Founding Fathers were all Christian believers who wanted to doctrinally establish the country as a Christian nation. While there were certainly Christians among the pool of politicians, historians remind Americans that not all of them were Christians— some were Deists or even atheists. Amid goals to secure independence and establish freedom in the country, establishing a state-sanctioned religious practice for all citizens would have been antithetical to these efforts.

Dangers of the ‘Christian nation’ idea

Still, many conservative politicians and Americans today believe America was founded as a particularly Christian nation and that decisions on government and law should be directly influenced by Christian principles.

This trope has led to a plethora of harmful beliefs throughout American history that prioritize political hermeneutics over legal doctrine, such as the various Scripture-based defenses of slavery and racial segregation in the Civil Rights era, or modern debates on the ethics of abortion.

And it is not just historians of American history who warn against the dangers of this trope, either.

Biblical scholars and religious historians urge this political use of Christianity is not responsible, nor is it accurate to the Bible’s historical context or intended spiritual use. The Bible was not written with American politics in mind, nor is being American an essential part of Christianity (or vice versa). Therefore, the Bible should not be used to forward any party or promote the power of any figure who chooses to interpret their own lifestyle, belief system and political goals as more favorable in the sight of God than whoever they consider the other.

Doing this, historians warn, is inevitably exclusionary. And not really “Christian.”

Christian nationalism

Instead, this political use of Scripture co-opts the religious and spiritual practice of Christianity and utilizes them as tools to politically manipulate American Christians into believing they are thinking, supporting and voting as God wants them to. This fusion of Christianity with American civic life, which rests on the idea that America always has been and always should be distinctively “Christian,” is a political framework called Christian nationalism.

Instead, this political use of Scripture co-opts the religious and spiritual practice of Christianity and utilizes them as tools to politically manipulate American Christians into believing they are thinking, supporting and voting as God wants them to. This fusion of Christianity with American civic life, which rests on the idea that America always has been and always should be distinctively “Christian,” is a political framework called Christian nationalism.

American Christian nationalism is antithetical to First Amendment rights established by our Founding Fathers, and it is not representative of the global and diverse community of faithful Christian believers. And many scholars of religion and theology, faith leaders or faithful believers are advocating against it.

Yet, politicians continue to utilize this framework to maintain the support of American Christians by promising their votes will support explicitly Christian politics and policy, and in turn, satisfy God.

In light of these debates, especially in the midst of rising temperatures in our political climate, Americans should heed the advice of historians and experts:

- The United States was not founded with the intention of being an explicitly “Christian” nation, and legal doctrines like the First Amendment were created to protect religious freedom for all people, including Christians.

- The translation and production of the Aitken Bible is an example of a particular moment in American history that reflects the time’s national desire to be independent from Britain but says little about the actual religious or spiritual culture in the nation at the time.

- Promotions of “Christian” politics and policy have been historically harmful and exclusionary in the United States, are not reflective of the First Amendment rights that establish a separation between the forces of church and state. This can be defined by the term “Christian nationalism.”

So, as Christians navigating all this, while the Bible has been utilized as a political tool throughout American history, let’s remember it was not written with America in mind, and our Founding Fathers did not want the religion to dictate a universal American identity.

Mallory Challis

Mallory Challis is a master of divinity student at Wake Forest University School of Divinity and is a former Clemons Fellow with BNG.

Related articles:

How to pick a Bible that’s right for you | Analysis by Mallory Challis

Baptists and the history of American Bible translation | Analysis by Dalen Jackson

Christian nationalism: A Baptist evaluation and response | Analysis by Ronald Cava