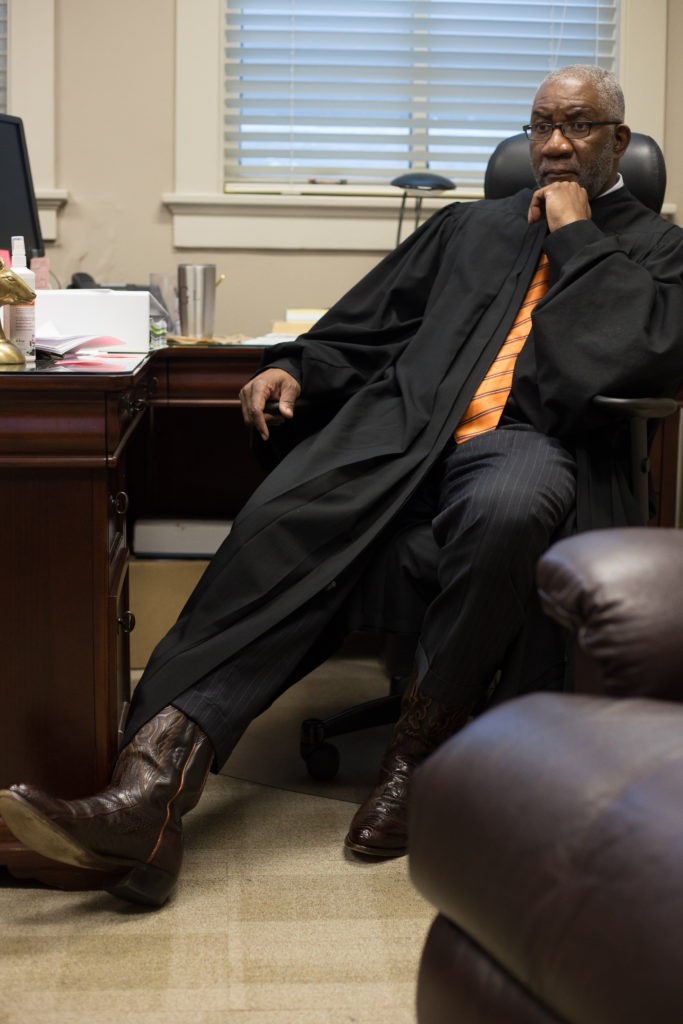

Cowboy boots beneath a pinstriped suit. Judge Griffen wears what’s comfortable. Photo by Brandon Markin.

Preacher Wendell Griffen believes the Bible is subversive, and he prefers not to describe himself as a Christian.

Judge Wendell Griffen quashes his state’s big, bold move to execute eight prisoners in a week; but he will gladly send you to jail if you keep messing up.

Husband Wendell Griffen grimaces when his wife holds him accountable after his own Sunday sermon about giving away a coat when you have two.

Activist Wendell Griffen lies on a cot in front of the governor’s mansion to protest the death penalty – then wins a judicial ethics battle against peers who think that behavior does not befit a judge.

Pastor Wendell Griffen leaves his lunch cooling on the table to help a 95-year-old member into her car.

Writer Wendell Griffen, a blogger, and a Baptist News Global opinion contributor, lambasts racists, subservience to empire, white privilege, the economics of incarceration, denominational politics and exclusionary policies by religious organizations that restrict full participation in all areas by LGBTQ persons.

Wendell Griffen, 66, is all of these things. But his persona is so large, his reputation so loud, his “rightness” so locked in and eagerly defended, that the man’s depth can be lost in the shallows in which he must wade.

Griffen burst onto the national stage on Good Friday 2017, when he – a sitting criminal court judge – protested the death penalty by laying on a cot in his white suit, hat on his chest, in front of the governor’s mansion in Little Rock, Arkansas, the town where he holds court and where he is pastor of New Millennium Church.

Griffen believes one should act on one’s convictions and because he does, he’s been a thorn to many leaders in government, politics, and religion. The Arkansas Supreme Court immediately barred Griffen from any dealings in the pharmaceuticals case and from all civil and criminal cases involving the death penalty or the state’s execution protocol.

He appealed, claiming the justices unconstitutionally deprived him of his rights to freedom of speech, freedom of assembly and the free exercise of religion, but on Feb. 19, the U.S. Supreme Court let that ruling stand by declining to hear it.

On a Sunday morning in December, Griffen is preaching from the New Millennium pulpit on “repentant living in an age of empire.” He used the analogy of seeing people drive the wrong way down a one-way street.

We need to flash our lights and honk our horn to tell them they’re going the wrong way. But it’s not enough to say, ‘Look at that fool.’ And it’s not enough for them to stop going the wrong way and sit dead in the road. You’ve got to help them turn around.

You’ve got to do stuff. Flash your lights. Honk your horn. If you don’t, you’re not being nice, holy people, you’re contributing to the oncoming, inevitable catastrophe.

Griffen is wearing a dashiki, an African shirt. He makes no mention of it, draws no attention to it. He just wears it, a colorful icon of his heritage – and a gift from his son who honeymooned in the Caribbean.

He tells of John the Baptist, who is preparing the way for the Lord to come. He compares John’s labor to the “dirt work” a construction company does to prepare to build a road. He notes that John called religious leaders of his day “vipers” trying to escape the coming destruction.

Quit being pawns of empire and do dirt work. We are the John-the-Baptist folks of this time, or we’re the vipers. Take your pick. We’re either warning about the vipers, or we are the vipers.

In Griffen’s world, vipers include those who marginalize or fractionalize any one of God’s creations, no matter their criminal record, sexual identity, ethnicity, age, income or religion.

He is particularly keen to stand for blacks and to educate whites whose privilege lets them see only through translucent lenses the continuing debilitation wreacked on blacks in America from the legacy of slavery. To those who would say, “It’s been 155 years since the Emancipation Proclamation, get over it,” Griffen points out – often to the aggravation of colleagues – that systems in America still reflect a plantation mentality.

In determining state representation for the new American Congress in 1787, southerners wanted their slaves to count in the population. A compromise was established that counted a black person as three-fifths of a person. That “fractionalization” persists today, Griffen argues, in how issues, influence, political power and pay for blacks are addressed.

It’s not enough for us to complain. We have to respond. We are called to honk horns and flash lights.

Ray Higgins, Cooperative Baptist Fellowship coordinator for Arkansas and a friend of 20 years, says Griffen’s theology “is very historic and orthodox. It’s the way he applies and lives it out and preaches that theology that makes him as controversial as John the Baptist in his day.

“His message only sounds radical when you’re only a part of your own majoritarian tribe. [New Millennium] Church embodies that gospel, seen in the people of different races and nationalities who not only make up the congregation but make up the leadership.”

“His message only sounds radical when you’re only a part of your own majoritarian tribe.”

Griffen speaks truth to power with clear, incisive language, the kind of words that raise howls of protest. His words and provocative actions also earned him charges of ethics violations – charges he continues to challenge.

When he found the Arkansas Department of Human Services in contempt of court for claiming not to understand an earlier order to “properly promulgate” its duties, Griffen called its leadership “imbeciles” for claiming ignorance of the term.

He is constantly willing to confront the infrastructure of empire and to kick the props out from under the social and cultural expectations of those who expect African Americans to “stay in their lanes.”

Can I get in your closet?” How many more than two of anything are we holding onto that we won’t give up – but others need? If I don’t empty my closet to help my enemy driving the wrong way, I’m a viper.

Pat Griffen, his wife of 44 years, is the first black doctoral graduate in psychology from the University of Arkansas and a newly minted trustee of Central Baptist Seminary. She calls him on this particular Sunday afternoon to remind him he has way more than two pieces of luggage taking up space in the attic. He shakes his head with a rueful awareness that the messenger’s message is not just for others.

Even when preaching, Wendell Griffen doesn’t separate himself from the people behind the weight of a heavy pulpit. Photo by Brandon Markin.

Whole of humanity

New Millennium member Regina Hunt, a psychologist, says her pastor’s approach to the gospel “is enlightening. I’ve grown tremendously, learned a different level of understanding to work out your life as a Christian in regard to the path Jesus set before us. It’s the gospel beyond church, tithes, and offerings. I’ve gained a deeper appreciation for the whole of humanity.”

The whole of humanity. If Griffen is trying to pierce the world’s calloused heart with any one message it may be that God is interested in, concerned for, weeps for and laughs with the whole of humanity. Every person is created in the image of God, and the barriers people erect to distinguish one from another are human divisions, not godly distinctions.

Griffen’s heart was nurtured by hard-working, loving parents in the tiny, rural community of Delight, Arkansas (population 262, according to the latest census). It was a farming and timber area, and Bennie Griffen worked in a sawmill during the day and plowed his land with a horse after that. A tractor came later. Josephine Griffen worked at a poultry processing plant.

For both, the work was tough, demanding and dirty. As dedicated laborers, they demonstrated the value of hard work.

The oldest of three kids, Wendell absorbed his father’s love of books, and he could read and write his name when he was five. At his two-room school, if you could read and write your name and count to 100, you were considered at least a second grader, so he spent about one day in first grade.

Today, Wendell’s sister, Sue, and brother, Danny, live near each other in Texas.

“God is interested in, concerned for, weeps for and laughs with the whole of humanity.”

Growing up in a small-town church, Griffen “didn’t get a lot of systematic theology,” but reading was required at home. His paternal grandmother, a domestic helper for a pharmacist, would bring home his used Reader’s Digests and condensed books to share with the family.

Despite his upbringing around books, his appreciation for education and a fast track through high school, Griffen flunked out after three semesters at the University of Arkansas. He started at age 16, the bright light from Delight, carrying the pride and hopes of his village.

Instead, the bright lights of college life blinded him. He was “cocky and immature,” playing cards, chasing girls and attending only the classes he liked. He was “too immature” to change his major from physics when he found himself as lost in trigonometry “as a mosquito in a hurricane.”

When he returned home, he was still just 17, too young to be drafted, too young to work in the paper mills or chicken plants.

Embarrassed then, Griffen says today getting dismissed “was the best thing that happened to me. It was my time in the wilderness. It forced me to go back to Pike County, humbled.”

He did odd jobs, hauled hay and helped his dad on the farm. Chagrined by his academic failure, he buckled down and took 12 course hours by correspondence. He regained admission the following August – on probation – but he studied hard and earned regular standing after his first semester.

Then, he found someone who believed in him. Major Richard Rogers, an ROTC instructor who knew him before he flunked out, encouraged Griffen to join ROTC, enticing him with the $75 a month stipend.

“When you’re the first born son of factory workers, $75 a month is a good idea,” Griffen says.

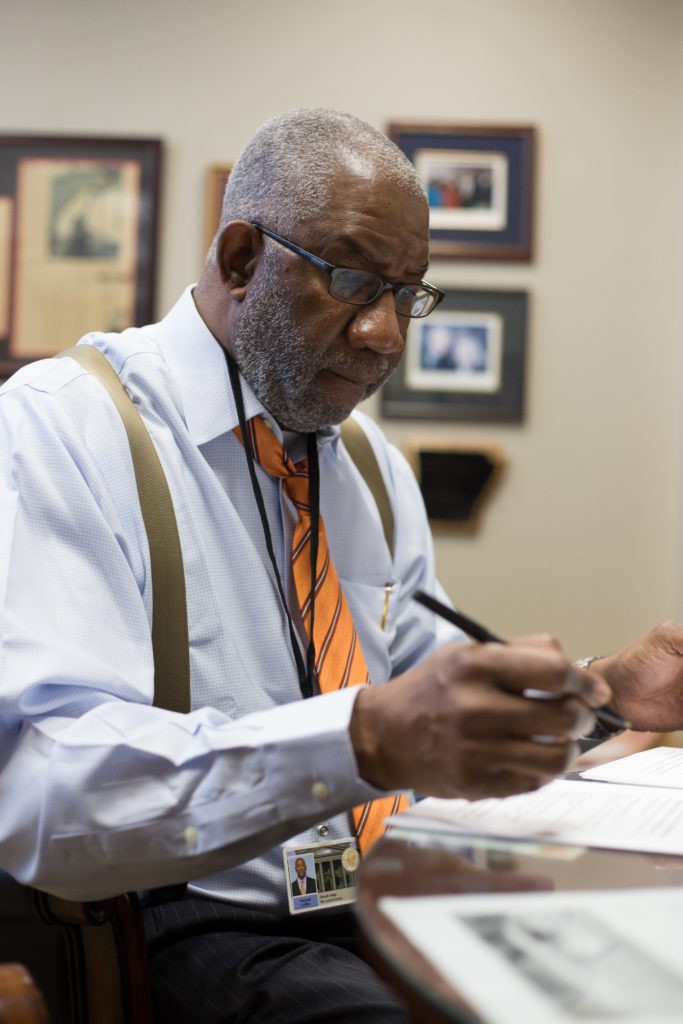

Judge Griffen prepares for the morning’s docket in criminal court. Photo by Brandon Markin.

Griffen reminded Rogers that he’d flunked out. Rogers still wanted him. Then the head resident of one of the university’s dormitories, Paul Steubbe, asked Griffen to be a resident assistant. Again, he confessed that he’d earlier flunked out. “I didn’t ask your grade point,” Steubbe said. “I know you, your character and your history. And by the way, as an RA your room and board are covered.”

Discovering that people believed in him solidified Griffen’s commitment to school and, along with his education, blew his worldview off its hinges. A German chemistry teacher, an Indian biology teacher – “people I never would have encountered in Pike County” – believed in him.

Undergirded by their confidence, Griffen – who flunked out of college in 1970 – finished in 1973 as a distinguished military graduate.

He immediately entered the Army as a second lieutenant, during the final, sad denouement of the Vietnam War. Trained as an artillery officer, he was stationed at Fort Carson near Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Morally indefensible

Although his father was a veteran and two uncles were career military, it didn’t take long for Griffen to realize he could not “morally survive” as a “cog in the militaristic defense system.” He still confesses a certain pride about his own service because of the experience it provided to work with people of different backgrounds. But he believes the nation must evolve a value system away from its willingness to resolve differences through war.

“Followers of Jesus are not questioning the unthinking acceptance of militarism as part and parcel of allegiance to Jesus,” he says. “How can we fail to do that, while preaching that Jesus was the victim of the Roman military empire? How can we put big ass flags in front of our churches and talk about ‘God bless our soldiers’… and support every war? So we promise to pray for the troops but we never try to counsel people to be conscientious objectors.”

“And saying we send chaplains isn’t enough. I don’t recall Jesus sending people two-by-two to counsel Pilate’s guards on being good troops, or telling them, ‘This is how you do an ethical crucifixion.’ What does it say about our notion of the religion of Jesus that we believe Jesus would commission people to become moral cheerleaders to murder on a grand scale?”

The voice of law calling Griffen to service was Justice Thurgood Marshall, not Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird. He saw law as liberating and powerful without being destructive.

“What does it say about our notion of the religion of Jesus that we believe Jesus would commission people to become moral cheerleaders to murder on a grand scale?”

As an artillery officer, he “learned to blow folks up” and he admits that access to power could have been intoxicating for someone growing up in the tumultuous civil rights era, someone who knew the frustrations of oppressive power.

“I’m part of the last generation of black people with first-hand memory of Jim Crow legislation and desegregation. I saw life before the 1964 Civil Rights Act and after; before Martin Luther King was murdered and after; before Vietnam and after. All of that informed and challenged my notion of faith.”

As a Christian, Griffen wrestled with the contrast between the peacemaking admonition of Jesus and his training to call down fire to destroy “enemies,” as defined by others. Then, he says, morph to today when anonymous soldiers in dark rooms watch video monitors and flip toggle switches to direct a drone to destroy a wedding party 7,600 miles away in Afghanistan.

“My faith,” he says, “was challenged by the Vietnam war, the assassination of Robert Kennedy, by being one of fewer than 200 black students among 10,000 students at a school where the fight song was Dixie, by Martin Luther King’s murder. All this at a time when I’m reading Malcolm X, Elijah Mohammed, and James Wright, and I meet Mohammed Ali and my faith is being stretched but also my worldview is being stretched.”

New Millennium member Josh McCallister moved his family from Chicago because they wanted to proclaim inclusion in the face of Little Rock’s iconic reputation as a seat of racism. They looked for a small church with black leadership in a diverse neighborhood, believing “intentional community is a solution for living out discipleship.”

If the Church will address deficiencies of the dominant culture, it will be “a demonstration plot for the kingdom of God,” he says. Such a garden grows at New Millennium.

“Let the greeting begin,” Griffen says, and members – at least 80 percent of them women – rise to mingle, hugging and greeting friend and stranger alike. The faces are friendly, warm, welcoming.

Griffen wants the Church to be as welcome and friendly a place universally. But, in his view, the Church has become so identified with its surrounding culture that it reflects the prejudices found in society, rather than being an instrument to overcome them.

After worship a group gathers to discuss The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness – not a typical Sunday Bible study topic. But the book’s emphasis clearly resonates with those around the table – educated southerners who have lived the prejudices, felt the verbal stabs and seen the vicious stares that come their way simply because their souls are wrapped in black skin.

Wendell Griffen’s persona presents no barriers, for young or old. Photo by Brandon Markin.

Today mass incarceration of young, black men is the topic. Griffen, initially reluctant to speak because the pastor’s first word tends to stifle conversation, is adamant about the relationship of the “theft of land, theft of liberty and mass incarceration.”

Early “settlers” dehumanized Native Americans by calling them savages, which made it all right to steal their land, notes Griffen. In much the same way, slaves survived by considering white slave owners as emissaries of Satan – and, therefore, not human – because no human could treat another human in that manner.

Mass incarceration is slavery by another name, Griffen adds. Consider the vast acreages being worked by prisoners to raise food. “If you don’t see that as slavery, you have blinders on.”

Though they make up less than 10 percent of the population, black males make up 35.4 percent of the jail and prison population. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, one in three black men can expect to go to prison in his lifetime.

Yet “Tom Cotton (Arkansas’s junior U.S. senator) says we’re under-incarcerated and faithful people aren’t calling him out,” Griffen says, shaking his head.

Jesus as mascot

These are issues that drive Griffen as a pastor, as a judge, as a Jesus follower – and as a human. He doesn’t call himself Christian, because “Christian” has lost its meaning in a day when obeisance to empire means church folks would vote against universal health care; would support a system that imprisons one in three black men; would cheer harsh immigration policies, rather than welcoming “the stranger,” and support a border security process that separates children and their parents by no-one-knows how many miles.

“They’ve killed the Christian meaning and have Jesus as a mascot,” says Griffen.

In America, incarceration has become big business. Private prison systems are listed on the New York Stock Exchange. In fact, a month after Donald Trump’s inauguration in January 2017, stock prices of private prisons doubled.

And, to Griffen’s utter dismay, civil rights icon Thurgood Marshall’s son is on the board of CoreCivic, a big, privatized prison operator.

Who are the snakes now?

He says the religion of white evangelicals is the religion of white supremacy and we have simply imported Jesus into it. “The rightness of whiteness. It makes slaves of all of us,” he says.

After warning his congregation from becoming the vipers in the John the Baptist story, and after lamenting the lack of interest in “The New Jim Crow” among his clergy peers during the book discussion, Griffen takes a late lunch at Layla’s, his favorite restaurant in all the world – a small, Mediterranean cubicle in a strip mall – where he is a familiar face. He is offered no ministerial or “favorite customer” discount, nor would he take one. He respects his friends’ need to earn a living.

“The religion of white evangelicals is the religion of white supremacy and we have simply imported Jesus into it.”

He likes the intimacy of small tables squeezed into tight space, the proximity to the clang and bang in the kitchen where the owner and his family work, the familiar faces and the various languages and clothing patterns he hears and sees.

Two of his church members, 95-year-old Margie Owens and musician Cindy Boyles, also chose Layla’s today. When they rise to leave, Griffen jumps from his chair and helps Margie out the door and into her car, letting his own lunch chill on the table.

As his friend, Ray Higgins observed the following day, “No one sees that side of Wendell.”

Back at the table, Griffen says the problem with Christianity is its identity with empire. He doesn’t want his identity with God to be associated with “oppressive capitalism, militarism” or any of the other isms that have tilted Christianity away from the liberal, embracing love of Jesus.

He had just heard that California mega-church pastor Rick Warren was being criticized for reaching out to Muslims by saying that Christians and Muslims worship the same God. “The idea that Rick Warren, as a follower of Jesus, could be criticized for reaching out to people whose faith includes Jesus – although not with the same perspective – is uncomfortable to me,” he says.

Of course, Griffen’s notoriety stems not from his role leading a small church in Little Rock, but because of his willingness to cross swords with political power brokers. He is backed by the strength of his convictions and is clear minded and outspoken in the face of controversy.

When he stayed the state of Arkansas’s killing business by ruling in favor of a chemical company’s right not to have its products used as the lethal ingredient in eight planned executions, he was roundly excoriated by local politicians and pundits.

“I had no right or power to cancel executions,” he says. “The only issue, in that case, was whether or not the owner of a pharmaceutical agent had a right to have that product returned because it had been obtained under false pretenses.”

State Sen. Jason Rapert told reporters that Griffen should “stay in his lane” and leave decisions about such matters alone.

Says Griffen, “I have been black long enough to know that means: ‘He’s an uppity nigger.’ This is a 21st-century reaction to the same thing Martin Luther King Jr. got when he trashed militarism and segregation – ‘He’s out of his lane.’

“I know the terminology. ‘He’s forgotten his place. Your place, boy, is over heah. How dare you tell white government what it can do? How dare you lay your black ass in front of the governor’s mansion and say to the world that the white governor and state of Arkansas have embraced a morally unjustified system of punishment? That ain’t your place. Anybody gonna to do that, it’s gonna be white folks.”

For Griffen, such reaction is neither new nor surprising. It’s the same reaction King got in Birmingham, Jeremiah got in Judah and Jesus got in Jerusalem.

“Jesus showed up at the governor’s mansion, you recall,” he says, over another bite of pita and tzatziki. “And it was the Jason Raperts of Palestine who turned Jesus over to Pilate. How would I expect to be treated differently from Jesus?”

Judge Griffen dons his clerical robe. He never uses his gavel because no one ever doubts who is the judge in his court room. Photo by Brandon Markin.

Human services

Griffen is both pastor and judge, dual roles that, to him, bear striking similarities. Both require respect for others, consideration of their circumstance along with the complexities of human existence, and analysis in the crucible of overarching principle.

As a judge, he sometimes must uphold laws with which he does not agree. He cites laws that shelter the strong against complaints of the weak. For example, no law entitles a tenant to an inhabitable dwelling. But laws prevent tenants from withholding rent to landlords whose property is basically uninhabitable.

Griffen started practicing law in 1979 and became the first black partner in a major Arkansas law firm. He almost left the University of Arkansas law school in favor of seminary, feeling the tug from both directions. He wrestled so much with the decision, his wife suggested he consider a sleep clinic.

He was licensed to preach in 1985 and took courses from Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Kansas City. But, in the midst of the Southern Baptist Convention controversy over the Bible, he decided “to hell with this.”

“I have enough sense of theology and church history to realize the whole inerrancy issue was an internecine food fight and the gospel of Jesus was being hijacked to advance the agenda of people who not only wanted to seize ecclesiastical power, but also political power. It was a crass exercise in empire building.”

“The whole inerrancy issue was an internecine food fight and the gospel of Jesus was being hijacked to advance the agenda of people who not only wanted to seize ecclesiastical power, but also political power.”

Instead, Griffen expanded his perspective by walking a block down from his law office to browse the Cokesbury bookstore. There he met the minds of Walter Bruggeman, Reinhold Neiber, James Cone, Henry Mitchell, Ella Mitchell, Samuel DeWitt Proctor, and others.

“Had there been no Cokesbury bookstore, I tremble to think what my notion of faith would be,” he says.

In a Black Studies course, he read Richard Wright, Eldridge Cleaver, and James Baldwin. Trained in law to think critically, his stable of author friends taught him to engage moral and metaphysical concepts.

Along with Cone, known as the founder of black liberation theology and one of his heroes, Griffen identifies the gospel of Jesus as the gospel of black liberation, “black being the moniker to identify oppressed people. It’s a gospel of salvation only if it’s a gospel of liberation. If it’s not a gospel that liberates us from all the things that oppress us, it is not salvific.”

In 1988 Griffen entered his first pastorate at Emmanuel Baptist Church in Little Rock while continuing his law practice. He led Emmanuel for 13 years, before returning to Mt. Pleasant Baptist – where he was ordained – as associate pastor. When the pastor retired, Griffen would have been considered for the position. But he realized his vision was not really suitable for a church rooted in tradition. He needed a church willing to be subversive.

So he started one.

Now 9 years old, New Millennium is generally composed of middle-aged and older persons. Membership is primarily black, but the worshipping family is multi-colored.

Its “meager” budget embraces missional living and ministry, including a bi-weekly food pantry. Griffen says it is the only Baptist congregation in Arkansas that is “open, welcoming and affirming” to persons who are LGBTQ.

“We’re fragile and strong,” he observes. “We’re a bantamweight that everyone says punches above our weight class.” He says the church considers itself neither rich nor poor. “We just are, so we depend on God.”

New Millennium’s congregation is 80 to 90 percent female, which is “a real problem in the church, especially the black church,” Griffen acknowledges.

“Established churches tend to be male-dominated, and men who grew up in Baptist life expect the church to be an extension of male dominance.”

Churches have always depended on women to function, he says, but have also treated women as a fraction. Established churches tend to be male-dominated, and men who grew up in Baptist life expect the church to be an extension of male dominance.

At New Millennium, women are empowered. The first person the church ordained to ministry, Anika Whitfield, was a woman. That example is encouraging for women, who want a church where they can exercise their God-given gifts, but Griffen knows that many men avoid churches where women are in leadership.

Worship services are participatory and interactive, with congregants leading prayer and reading scripture. Griffen sits in a pew until it is his time to preach. When Pat Griffen led the prayer on this Sunday, it was as “Pat,” not as Dr. Griffen, or as the preacher’s wife.

When he’s not leading the service, Pastor Wendell Griffen sits in a pew among the congregants. Photo by Brandon Markin.

Prodigious work

As a judge, pastor, husband, father, activist, writer and community leader, Griffen produces a prodigious amount of work, yet says simply, “I’ve got the same 24 hours everybody else has got.”

He shrugs off his load by pointing to his parents. His dad worked at the sawmill – sometimes 55-hour weeks – then came home and worked his 40-acre farm. On Saturday nights he shined shoes and cut the kids’ hair, took a bath and read the Sunday school lesson. On Sunday mornings he opened the door at church.

Once, when Griffen’s mother visited him in judicial chambers, she commented that he must not really be working because his shirt wasn’t even wrinkled when he got home. So, he denies that anything he’s doing is “heroic.”

“My challenge is whether I’m making best use of the time, whether I’m doing enough.”

He cringes when he thinks of closing his ears to at least two books crying out to be written. One is an obvious call for a memoir. The other is a treatise on the re-identification of Jesus by the church in America.

“We’ve crucified the truth about Jesus and domesticated Jesus for empire.”

“Instead of a subversive who personified the truth of God, we’ve crucified the truth about Jesus and domesticated Jesus for empire,” he says. Now immigrant Jesus is used to defend policies of xenophobia; labor class Jesus is used to defend oppressing workers; Jesus, whose closest friends and “first to the tomb” were women, is used to marginalize women; Jesus who didn’t own a donkey and was literally homeless is used to justify materialism.

“White religious nationalism and white supremacy is the dominant theology of this nation, and the religion of Jesus has been not just hijacked, but murdered,” he says. “The crucifixion was a murder but it also was a political assassination. This is the mugging of Jesus, the stoning of Jesus. I’ve got to get that out of me, some kind of way before the Lord calls me home.”

Griffen excoriates professional colleagues and other church and denominational leaders with the same sharpened quill. When Southern Baptist Theological Seminary released a self-examination of the slaveholding history of its early leaders, Griffen, in an opinion article for Baptist News Global, criticized current SBTS President Albert Mohler for omitting reference to “the most recent instances of racism, white supremacy and white religious nationalism practiced and perpetrated at and by SBTS.”

Both Griffen and his wife, Pat, have served on the Arkansas CBF Coordinating Council and Pat served a term as moderator. Griffen nominated recently retired Suzi Paynter as executive leader for CBF national, after serving on the search committee that identified her for the role. Those connections did not dissuade Griffen from leading New Millennium to cut ties with national CBF after its governing board voted to continue the organization’s ban on hiring LGBTQ individuals as missionaries or in some staff leadership positions.

To Griffen, that decision “sounded very much like ‘separate but equal,’ which is only separate; it’s not equal. And for them to have done that, using allegiance to the Great Commission as the pretext, flew in the face of everything we’re trying to be at New Millennium.”

“How is homophobia consistent with the love ethic of Jesus?”

Griffen has performed same-sex marriages in his chambers. As a judge, he struck down an Arkansas ban on issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples. “So there is no way in the world,” he says, that his welcoming and affirming congregation could embrace an organization that would deny one of them the opportunity to be hired as leaders of CBF.

“How,” he asks, “is homophobia consistent with the love ethic of Jesus?”

He cites God using a eunuch to take the gospel to Africa and that Jesus “turned the whole notion of who can be acceptable on its head when on Easter Sunday Jesus ordained women as missionaries. It was women who took the message of the risen Jesus to the men, and it was the men who didn’t believe.”

He says it’s “ironic” that an organization with a female leader would ban other minorities from serving as missionaries.

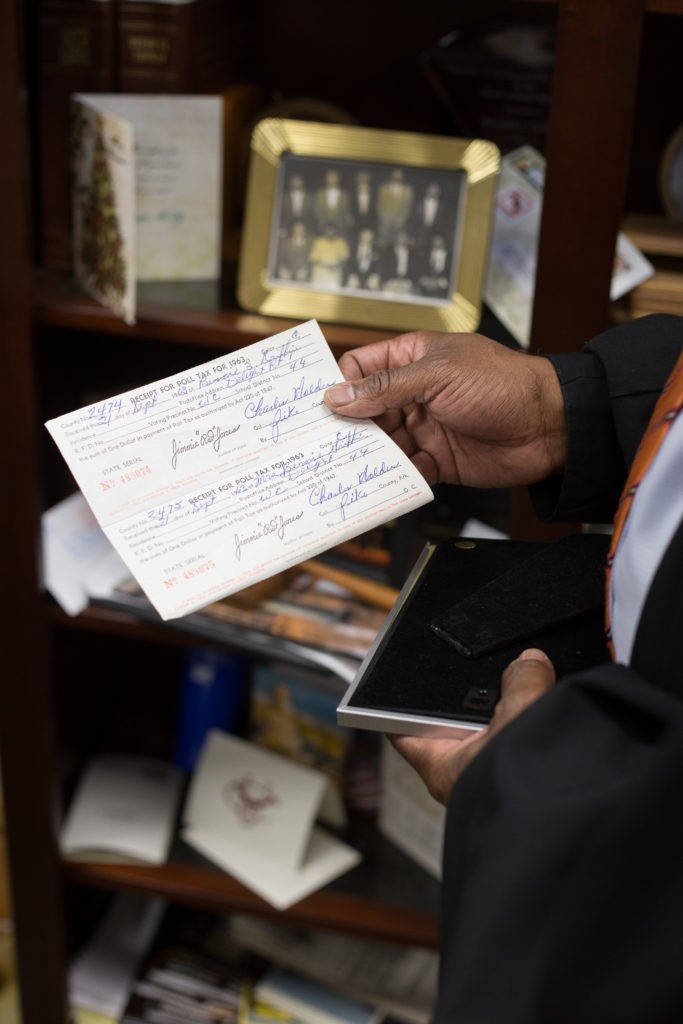

Judge Griffen holds the 1963 poll tax receipt paid by his parents in Arkansas. He bristles that states today are trying to pass restrictive voting identification laws. Photo by Brandon Markin.

Poll tax receipt

Relaxing in his chambers in a pinstripe suit and cowboy boots, Griffen reaches for the framed receipt of a Sept. 21, 1963, poll tax paid by his parents. To him, it is a “warning not to forget that past history is a reliable predictor of future conduct.”

State governments pressing to pass photo ID voting laws reflect white supremacy in a society that “was not set up to be governed by women and people of color,” he says, crediting his own position of authority as a judge to the battles fought by others.

Also on the shelves are a can of tea and a bag of Skittles – the snack items that Trayvon Martin went to buy on the night he was shot by a neighborhood vigilante.

Griffen sometimes uses a Darth Vader mask in class to demonstrate to law school students that the law is “the Force.” “Trust the Force,” he tells them, “but don’t get on the dark side.”

He’s proud of a group picture with President Lyndon Johnson and National FFA Organization members taken at the White House when Griffen was 15.

Mementos like these remind him of who he is, where he is, how far he’s come, and the sacrifices made by so many others so that he could get here.

Under the glass cover on his conference table is a picture of black demonstrators being beaten, under an ironic label saying, “A Christian nation.”

“Remember history,” Griffen warns. “When you know where this country has been you’re never surprised where it goes.”

On this morning, before walking a few steps to conduct court from the judge’s bench, he’s asked whether he rules his courtroom or presides over it. He responds that he “interacts.”

“Law is human services work,” he explains. “My job is to see how to serve the general public as I deal with these humans. They are humans. That person has to feel like they had a human being dealing with their situation.”

In the courtroom, Judge Griffen interacts with both lawyers and defendants, telling defendants he doesn’t want to send them to jail, but if they continue their course, he’ll have no choice. He asks one how many strikes a baseball player gets before he’s called out.

“Three,” says the defendant. “This is your second,” Griffen says. “Next time you’re here, you better hit something.”

“Remember history. When you know where this country has been you’re never surprised where it goes.”

Many who appear before him are there because of drug problems, another issue that can make Griffen’s blood boil.

“What makes a certain conduct a crime?” he asks, wondering why some addictions are considered a crime and other addictions are not. He believes the “war on drugs is nothing more than a war on people.”

When arrests were predominantly among poor minorities, drug use and possession were punishable crimes. Now that the scourge has seeped into the broader society – read ‘white’ – “now the call is for treatment.”

Griffen greets staff, public defenders and advocates by name. He refers to defendants as “sir” or “ma’am.” He apologizes to a retired military officer up for repeated drunk driving offenses for not calling him “Major” when he addressed him earlier.

He rearranges the docket so that Rev. Robinson, who runs a recovery home, can speak for each of his clients consecutively so he can get back to his important work.

Higgins, who served as a pastor in Little Rock before assuming his position with CBF Arkansas, has known Griffen for 20 years. He insists it’s not the racism and discrimination Griffen has faced all of his life that makes him controversial. It’s that he chooses not to live silently within the confines of American culture’s white, male, conservative rules about women, race and sexual orientation.

“Wendell is one of the smartest people I know,” Higgins says. “In any room full of attorneys and judges, he’ll be one of the smartest, most articulate, most culturally competent and most able to evaluate a wide range of ideologies of any person in the room.”

For many, Griffen’s “public image is as an obnoxious, African American know-it-all who won’t stay in his lane, who talks too loudly and who has a chip on his shoulder,” adds Higgins. “What they don’t see is the people he pastors and visits in the hospital and does their funerals. He prays for them and cares for them.”

“He really is a pastor and a prophet.”

Wendell Griffen left his lunch cooling on the table to help 95-year-old member Margie Owens into the car. Photo by Norman Jameson.

Read more in the Wendell Griffen series:

Racially diverse church occupies campus where Baptist pastor once proclaimed racist views

Photo Gallery: Wendell Griffen

Related commentary at baptistnews.com:

White Baptists and racial reconciliation: there’s a difference between lament and repentance | Wendell Griffen

Gov. Northam is not an outlier: American Christianity’s tolerance for white supremacy | Wendell Griffen

Related news at baptistnews.com:

Arkansas plan to execute 7 men in 11 days strengthens faith, death penalty opposition

No forgiveness for slavery, racism without repentance, CBF pastor says

This series in the “Faith and Justice” project is part of the BNG Storytelling Projects Initiative. In a 1967 address to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Martin Luther King Jr., exhorted people of faith to “realize the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” We tell the compelling stories of the people and organizations that are helping to bend the “arc of the moral universe” toward justice and, in so doing, are transforming the communities where they live.

Judge (and pastor) Wendell Griffen speaks truth to power with clear, incisive language, the kind of words that raise howls of protest. But it’s not the racism and discrimination Griffen has faced all of his life that makes him controversial. It’s that he chooses not to live silently within the confines of American culture’s white, male, conservative rules about women, race and sexual orientation.

_____________

Seed money to launch our Storytelling Projects initiative and our initial series of projects has been provided through generous grants from the Christ Is Our Salvation Foundation and the Eula Mae and John Baugh Foundation. For information about underwriting opportunities for Storytelling Projects, contact David Wilkinson, BNG’s executive director and publisher, at [email protected] or 336.865.2688.