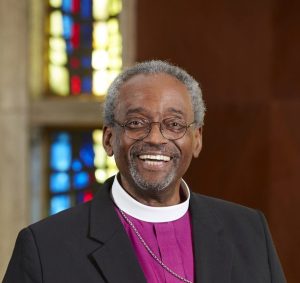

Michael Curry was elected 27th presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church in 2015, after previously serving as bishop of North Carolina. One of America’s most-renowned preachers, he is perhaps most widely known for his sermon at the “royal wedding” of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle. I am grateful for Bishop Curry’s life and witness and for his willingness to reflect on both as he steps down from office.

Greg Garrett: Bishop, you are the first Black presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church, and as you sometimes say, you’ve been Black your whole life. What challenges and opportunities around racial healing have driven your tenure? How have you and our church wrestled with recent American cultural and political movements that have embraced racism and anti-immigrant rhetoric as normative?

Bishop Michael Curry: Well, I have to say the the Episcopal Church has long been involved in the work of racial justice and reconciliation under the rubric of a variety of names, whether it’s racial justice and reconciliation or the work of the Beloved Community.

Michael Curry

I was elected presiding bishop at the convention that was going on right after the killings of folk at Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, S.C. I was elected presiding bishop after the Supreme Court decision granting the possibility of marriage equality in the United States. And I was elected when there were still debates about reform of the immigration system, debates which continue to this day. If you think of those three things and add on to it the first Council of Paris around the environment and climate change and the need for the nations to do something, put all of that together, and you get the scope of the Episcopal Church’s engagement with the world, with the reality of the world, from racism to the planet on which we live.

I don’t think that was because I was an African American bishop. It just so happened to be the case. But I do think that, if you will, the stars kind of aligned, or as we would say, it’s like God was trying to do a new thing and send a message, to encourage us in the work of helping to transform the world in which we live from the nightmare that it often is for so many into something that is closer to God’s original dream and vision for the creation when God said, “Let there be.”

That’s where the work of redeeming this creation comes from. It comes from the heart of God who so loved this world that he gave his only begotten son. It is out of that love of God for this world that we as a church are committed to participating in ending the man-made nightmare and helping us to realize God’s dream for all of God’s children.

GG: Love is the central value you’ve espoused as presiding bishop, and I’ve heard you preach it in American churches and seminaries, at ordinations and at a British royal wedding. Could you speak a bit about why love has been a central message for you and how you believe it might reshape our private and public lives?

MC: I grew up in a predominantly Black Episcopal church in Buffalo, N.Y., where every Sunday in the 1928 Prayer Book when we had holy Eucharist, we heard the words, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, mind and strength, and your neighbor as yourself. On these two hang all the law and the prophets.”

“Once you hear something every Sunday, it seeps into your brain.”

Now I’m not sure I was paying attention. But, you know, once you hear something every Sunday, it seeps into your brain, into your consciousness and into your unconscious. I grew up in the home of a father who was engaged in the work of civil rights as an Episcopal priest, and the language of love was the language of that movement. I mean, it just was.

I just have always grown up believing the way of unselfish, sacrificial, or as Dr. King would say, redemptive love, is the way of the Cross. It is the way of unselfishness. It is the way of seeking the good and the well-being of others as well as the self.

Some years ago, I wrote a book, Songs My Grandma Sang. I went back and was thinking about songs she either sang or referred to. One of them was “There is a Balm in Gilead,” and one of the verses says, “If you cannot preach like Peter and you cannot pray like Paul, you can tell the love of Jesus, how he died to save us all.”

Now think about that for a moment. These were enslaved people singing about the love of Jesus who died to save us all. “All” included them and those who enslaved them.

That is a stunning thing to think about. And then they said, that’s the balm in Gilead that can heal the sin-sick soul. That is the balm in Gilead that can transform this world from a nightmare into God’s dream. Now take all of that and go back to the Bible itself.

When Jesus and that lawyer in Matthew 22 had that conversation and the lawyer asked him, ‘What’s the greatest commandment in the legal edifice?’ that lawyer was asking what is the most important thing in the law of God. What matters ultimately to God?

Jesus went back to Deuteronomy and Leviticus, to the Shema in Deuteronomy: “Hear, O Israel. The Lord our God is one. You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, mind and strength.” And then he added Leviticus to it: “And you shall love your neighbor as yourself. On these two hang all the law and the prophets.”

“This is the supreme law of God: to love God and to love your neighbor as yourself.”

This is the constitution of God. This is the supreme law of God: to love God and to love your neighbor as yourself.

That’s not Michael Curry. That’s the Bible.

Better yet, that’s Jesus. That’s what Jesus said, and it’s in all four Gospels in one way or another. When the Bible repeats itself, pay attention.

And so I’m not the one suggesting this way of unselfish, sacrificial love is the core of the word of God. It’s the core of what Jesus was about, and it’s the core of who God is.

Look, for example, at First John, chapter 4: “Beloved, let us love one another because love is of God. And those who love are born of God and know God. Those who do not love, do not know God.” Why? Because God is love. Doesn’t get clearer than that.

And so this love is the key to true justice that is not mere revenge. This love is the key to creating relationships, societies and a world where we treat each other as sisters, as brothers, as siblings, as members of the human family of God.

This love, unselfish, sacrificial, that seeks the good and the well-being of others is the key to how we will lay down our swords and shields down by the riverside and study war no more.

Love is the key. And if you don’t believe me, ask Jesus.

GG: You’ve spoken about the menace of white Christian nationalism. What do you see as steps American Christians can take to push back against white Christian nationalism and how we can reclaim or reassert the central teachings of our faith?

MC: Well, it’s important to become aware of the perversion of Christianity, the perversion of the gospel message itself. Christian nationalism ties white supremacy and racism to the superiority of Christianity over other religious traditions and makes an unholy alliance of those two. It is a perversion and a distortion of the Jesus who told the parable of the Good Samaritan. Jesus said that’s what it looks like to be a neighbor. That’s what it looks like to be human as God intended.

Jesus told that parable as he was heading toward Jerusalem, toward the Cross. So that perversion, that distortion, is a twisting of the gospel of Jesus Christ.

You can’t condone racism if you believe in the gospel.

You can’t condone homophobia if you believe in the gospel.

You can’t condone antisemitism if you believe in the gospel.

You can’t condone — I mean, I could go through the list. You can’t do it.

“You can say you believe those things, but you can’t say you believe them in the name of Jesus.”

Now you can say you believe those things, but you can’t say you believe them in the name of Jesus. As the hymn says, “The king of love, my shepherd is, whose goodness faileth never.” You can’t do it. Now you can do it in some other name, but not in the name of Jesus.

If it’s not about love, it’s not about God.

I don’t care how many Bible passages are quoted. I don’t care how holy and religious and sanctimonious it sounds. If it’s not about love, it’s not about God, and white Christian nationalism or any Christian nationalism, anything that tries to make anybody superior to anybody else, is not about Jesus Christ, who said the last shall be first and the first shall be last.

It is not about the gospel, about Mary who sang the Magnificat: “My soul hath magnified the Lord. He hath put down the mighty from their seed and hath exalted the humble and meek.” It is not about the Jesus who said, “By this, everyone will know that you are my disciples, that you love one another.”

GG: As you reflect on your time as presiding bishop, what are some of the things that have brought you joy and peace, either in your personal life or in the corporate life of the church? What advice would you offer those who feel overwhelmed, worried or fearful about the future?

MC: As a presiding bishop, you really do get kind of a macro picture of the people of the Episcopal Church, to be sure, but also of the Anglican communion, a church of 80 million people. I think of Christianity itself writ large and of people of different religious faiths and traditions — you get to see some remarkable people. I mean, really remarkable people who each in their own ways keep this world better than it would be if they didn’t.

So while there’s a lot to be concerned about in the world, there is more good among us than bad. Dr. King once said the moral arc of the universe is long, but it is bent toward justice. Well, he got that from a 19th-century abolitionist who was writing to encourage people who just thought slavery never would end.

“Christ is risen. Death could not beat him, and it will not beat us. That’s not optimism. That’s realism. That’s faith in God.”

If there is a God, if there is a God, as I believe there is, and if this God is love, then love is going to have the final word. In the end, love is going to win.

“The powers of death have done their worst, but Christ their legions has dispersed. Let shouts of holy joy outburst.”

Alleluia. Christ is risen. Death could not beat him, and it will not beat us. That’s not optimism. That’s realism. That’s faith in God.

There is a story about Frederick Douglass, during the Civil War here in the United States. It was, you know, a tough, tough time. He was trying to get Lincoln to move further than he had. The war was not going that well. And Sojourner Truth happened to be in the room, the two of them were in the room, and he was just despairing. And she, as folks say, got in the space.

And she said, “Frederick, is God dead?”

If God is not dead, then neither is truth, neither is justice. And if God lives, then justice will be done. Thy kingdom will come on earth as it is in heaven.

Doggone it — against the odds, I believe it.

And we who follow Jesus of Nazareth, even when we doubt it, are committed to living that truth.

Love is going to win because God is love, and nothing can stop or defeat God.

Greg Garrett

Greg Garrett is an award-winning professor at Baylor University, where he is the Carole McDaniel Hanks Professor of Literature and Culture. One of America’s leading voices on religion and culture, he is the author of 30 books, most recently the novel Bastille Day and The Gospel According to James Baldwin: What America’s Great Prophet Can Teach Us about Life, Love, and Identity. He is currently administering a major research grant on racism from the Eula Mae and John Baugh Foundation and finishing a book on racist mythologies for Oxford University Press. Greg is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church and Honorary Canon Theologian at the American Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Paris. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

More from this series:

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Melissa Deckman

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Matthew D. Taylor

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Nancy French

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Robert P. Jones

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Brian Kaylor

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Colin Allred

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Tia Levings

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Linda Livingstone

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Samuel Perry

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jimi Calhoun

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with David Dark

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Randolph Hollerith

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jillian Mason Shannon

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Vann Newkirk II

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Sarah McCammon

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Winnie Varghese

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Kaitlyn Schiess

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Russell Moore

Politics, faith and mission: A BNG interview series on the 2024 election and the Church

Politics, faith and mission: A talk with Tim Alberta on his book and faith journey

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jemar Tisby

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Leonard Hamlin Sr.

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Ty Seidule

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jessica Wai-Fong Wong