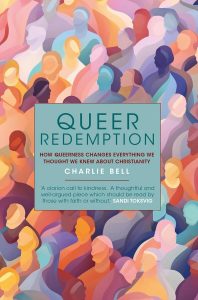

Earlier this year, I had the great opportunity to get to know Charlie Bell, who is a forensic psychiatrist, the John Marks Fellow at Girton College Cambridge, a priest in the Church of England, and scholar in residence at the Cathedral of St John the Divine in New York City. Since Charlie is someone with knowledge of both U.S. and UK contexts — and a leading advocate for queer voices in the church — I am so grateful to talk with him about his new book Queer Redemption and what those on the so-called mainstream can learn from voices on the fringes.

Greg Garrett: Charlie, your new book Queer Redemption continues your exploration into how queer theology might be a gift to the larger church. How could “queering” the church open up important conversations and understandings of where Jesus is, what the church is, who we are?

Charlie Bell

Charlie Bell: I have to admit that I come to the idea of queering as someone for whom this has not been my bread-and-butter theology. I’m from a fairly traditional and mainstream theological tradition, albeit one that has always been helpfully challenged by the radical and the outsider. Yet the more I read in queer theology, and about queering more generally, the more it became clear to me that what queering offers the church is an opportunity to refine and really question the assumptions that underlie so much of the theological enterprise.

We are, for example, really used to talking about unchangeable doctrines, or the clarity of Scripture, yet we aren’t so good at questioning the questions we are asking. In other words, what is the unchangeable thing, or essence, of marriage — what are the right questions to ask Scripture in the first place, and why?

Although by its nature queering is a contested thing and operates more as a positionality rather than a theology, it does allow us to do three important things.

The first of these is to really listen to, and allow ourselves to take a breath before responding to, the experience of LGBTQ people of faith.

The second is to offer a challenge to the presumed theological importance of social and cultural norms as relates to sexuality and gender.

And the third is to build on that, by breaking down these boundaries and allowing the transgressive to be spoken.

I have found the more we are willing to do all these things — and do them as part of a wider intersectional theological enterprise — the more we are able to actually engage with the world as it is and not merely as we wish it were. In doing so, we are able to talk about God, rather than the god we wish into existence.

GG: You were asked if the liberation you seek is just for white middle-class men to marry, and of course you concluded it is not. Can you talk about what queer redemption is seeking?

CB: This was such a great challenge put to me by an ordained Black woman during a talk I did a year or so ago. So many of our debates on sexuality end up returning to conversations about marriage, and that’s important because I really do think marriage is important. Yet we cannot merely engage with marriage by making everyone an honorary heterosexual.

“We cannot merely engage with marriage by making everyone an honorary heterosexual.”

My thesis in Queer Redemption is that we make marriage better, more like its essence, if we listen to the voices of queer people and understand the new things that are being said about this state of life.

Similarly, while marriage might be a holy estate, to quote Cranmer, I don’t think it’s our starting point in discussions and debates on matters of sexuality and gender. What we really need to do is to ask the serious questions about human relating, about intimacy, about sex, about intercourse, about fidelity, about the holy life — and then once we’ve engaged with these much deeper questions about what it means to be fully alive in the Spirit of God, we might begin to engage with something as contested as marriage.

So queer redemption is about a transformation of how we do our theology, how we order our churches, how we work our way, however slowly, toward the life of grace we are all called to. It’s a work of theological anthropology, and one that is going to surprise us along the way, because it won’t allow questions to be unasked — even if we might not yet have the full answers.

So queer redemption is about a transformation of how we do our theology, how we order our churches, how we work our way, however slowly, toward the life of grace we are all called to. It’s a work of theological anthropology, and one that is going to surprise us along the way, because it won’t allow questions to be unasked — even if we might not yet have the full answers.

And it’s a path I truly feel we are called to walk along, because God really isn’t afraid of us asking questions.

GG: The Church of England has been less than generous in its treatment of LGTBQ people, and of course here in America we’re facing a backlash against queer rights and legal recognitions we’d thought were legally and culturally accepted. Can you speak a bit from your vantage points as psychiatrist and priest about the damage done to those outside the straight white Christian mainstream by exclusion and prejudice?

CB: It was my work as a psychiatrist that really got me thinking more deeply about questions of sexuality and gender. It’s so easy to do the mental gymnastics of separating out people from theology, and on matters of sexuality we have been extraordinarily good at that. We so often hear people talk about the “good news” for LGBTQ people, without really interrogating whether that good news can move beyond the abstract into the real and lived.

“Our complete inability to recognize the harm we are doing … is as depressing as it is inappropriate.”

As you hinted at, in my own context the debates on LGBTQ loves and lives have been extraordinarily toxic, and people have either quietly left the church or stayed and continued to be hurt. Our complete inability to recognize the harm we are doing, and our endless ability to talk in terms of false equivalence about hurt “on both sides” in debates on sexuality is as depressing as it is inappropriate.

LGBTQ people face extraordinary prejudice, leading to severe consequences for their mental health and general well-being, and yet it is they who are so often painted as promoters of division, problematized and gaslighted. And the most scandalous thing is that the church and Christians are not merely participants in this abuse, but often its architects. Through history, we’ve seen that this has so often been the case with minoritized groups, and yet here we are, doing it all over again.

The exclusion we mete out on those different to ourselves comes in so many different flavors, including othering, scapegoating and outright denial of their existence, yet they all ultimately come down to our inability to recognize the face of Christ in someone who is different from ourselves, and our unwillingness to believe they are created in the image and likeness of God in the same way that we — in an act of God’s extraordinary abundance — are.

GG: You’ve just gone through a general election in the UK, and we are mired in one in the States. Although I celebrated your outcome in the UK, I also know we are in a moment where people across the West are seeking to claw back dominance for straight white Christian males and to denounce the “other” as dangerous and deviant. What concerns do you have about religion and politics in either of our settings this year?

CB: This is a great point. One of the most depressing parts of the election campaign here was the active choice of the then-government to use transpeople as dispensable collateral in their attempt to whip up a culture war. Our former Home Secretary is on record as calling the Progress Flag “monstrous,” and I’m afraid that is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of some of the political rhetoric we faced over the past six weeks.

I’m glad the general public didn’t seem, in the main, that keen on this kind of miserable posturing, but I do fear the tide has, if not turned, then at least stalled in the rolling out of LGBTQ rights and the addressing of past wrongs.

“Many churches in my context are so caught up in their own fights and divisions that they seem unable or unwilling to at least speak about the human dignity of all people.”

Many churches in my context are so caught up in their own fights and divisions that they seem unable or unwilling to at least speak about the human dignity of all people, and the Church of England is totally unable to speak with a prophetic voice on matters of social justice while it continues to actively discriminate against LGBTQ people despite being the established church.

The picture in the U.S. is perhaps even more bleak, with the overt politicization of the Supreme Court and the apparent willingness of politicians to use queer and other minoritized people as tools in their power grab.

The “victim culture” of whiteness is utterly pitiful, yet it seems powerful too, and our churches need to speak into this space in language which is theological and not merely sociological. Ultimately, we shouldn’t really be interested in a culture war — we are interested in trying to formulate theological truths for a world that God loved enough to send Jesus to save. If we — and by this, I don’t only mean churches, or even Christians in public life, but Christians in our day to day dealings with one another and the wider world — are unable to even speak of dignity and love, then I wonder what exactly we think we’re doing.

We need a revolution of kindness and holiness, and when so much of the world is growling and gnashing its teeth, surely it is time to call our hearts and minds back to the silent night when the Savior of the world called us to participate in his reign of peace, joy and love.

GG: Because sometimes the world seems so daunting, I’m asking everyone I talk to where they are finding hope, insight or courage. I wonder if you have things you’re reading, watching, listening to or experiencing at this moment that are reminding you that we live in a world Jesus already has redeemed? Thanks so much for your engagement, Charlie.

CB: The most hopeful thing for me has been the increasing recognition of the importance of intersectionality in our dealings with one another. This means for queer Christians, we need to take the historic and current prejudice of our society and our church against Black and other (global majority) people seriously, and to see it as part of the wider struggle for liberation in which we are all called to play our part.

Similarly, I am increasingly hopeful when I see Christians who are straight white males realize this liberation is not merely about liberating those of us who are not that, but about actually enabling the church to more fully realize its calling.

Seeing our bishops here in England start to be honest about their disagreements, and to see non-LGBTQ bishops start to not only advocate for but amplify LGBTQ voices is, I hope, the start of a new way of ensuring the unheard voices might find a space at the table.

After all, the table is God’s, not ours — and the more we can remember that, the more we might live into our call to be God’s body broken, shared and sanctified.

Greg Garrett

Greg Garrett teaches creative writing, film, literature and theology classes at Baylor University. He is the author of two dozen books of fiction, nonfiction, memoir and translation, including the critically acclaimed novels Free Bird, Cycling, Shame and The Prodigal. His latest novel is Bastille Day. He is one of America’s leading voices on religion and culture. Two of his recent nonfiction books are In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

More from this series:

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Grace Ji-Sun Kim

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Rowan Williams

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Nathaniel Jung-Chul Lee

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Starlette Thomas

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Samuel Perry

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jimi Calhoun

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with David Dark

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Randolph Hollerith

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jillian Mason Shannon

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Vann Newkirk II

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Sarah McCammon

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Winnie Varghese

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Kaitlyn Schiess

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Russell Moore

Politics, faith and mission: A BNG interview series on the 2024 election and the Church

Politics, faith and mission: A talk with Tim Alberta on his book and faith journey

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jemar Tisby

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Leonard Hamlin Sr.

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Ty Seidule

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jessica Wai-Fong Wong

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Brian McLaren