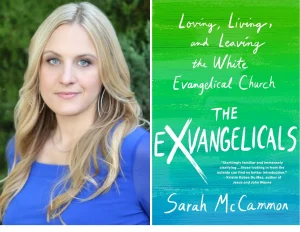

Sarah McCammon is a national political correspondent for NPR (covering Donald Trump in the 2016 election), co-host of the NPR Politics Podcast, and the recipient of a 2023 Edward R. Murrow Award for her coverage of the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision. Her work focuses on political, social and cultural divides in America, including abortion policy and the intersections of politics and religion. Her new book The Exvangelicals: Loving, Living, and Leaving the White Evangelical Church is a marvel of reportage and memoir, joining powerful recent works by Russell Moore and Tim Alberta in chronicling the drift of white evangelical Christians in the pursuit of political and cultural power and the need to construct a useable faith in the face of that tradition’s failures. I’m so grateful to Sarah for answering my questions as she launches her new book.

Greg Garrett: In The Exvangelicals, you share your story and the stories of many others who have walked away from the whole evangelical culture. You describe personal revelations all the way through the book, but could you tell us the major reasons you ended up stepping away from evangelicalism? What have been the biggest drivers for other exvangelicals to leave the church?

Sarah McCammon

Sarah McCammon: As I describe in the book, I felt a sense of cognitive dissonance about many of the things I was being taught from an early age. Much of it had to do with my grandfather, who was one of the few non-Christians I knew, and who, I would discover, had come out as gay after my grandmother’s death. My evangelical community’s ideas about people who held different beliefs from ours or simply were different from the ideal the church promoted came into sharp conflict with what I knew about him. And as I grew older, I began to feel that many of those beliefs were separating me from other people more than forging connection.

In the course of my work as a political reporter, many years after I made my personal and private break with evangelicalism, I came to discover an online community of others who’d walked similar paths. At a moment when evangelicalism was at the center of many political stories, I found that many people who’d grown up in a similar environment were also re-examining their faith and their relationship to the evangelical culture. Many were turned off by the deepening political divide in our country and the intensifying politicization of the evangelical movement, and by their churches’ responses to issues including race and the COVID pandemic.

GG: You covered Donald Trump during the 2016 election, and in the book you describe encountering the hatred of his supporters as a member of the press. You’ve had a close look at his appeal to evangelical Christians, and you’ve also noted how he drove people away from their faiths. As you reflect on the relationship of Trump and evangelicals, what are two or three important things we should remember? Is any appeal possible to evangelicals on this question, or will it take, as Tim Alberta told me and Tyler Burns told you, the death of this iteration of the church for something good to be reborn?

“Despite the fact that conservative voters had many other options available in the 2024 Republican primary, evangelicals once again are strongly supporting him.”

SM: Early on, evangelicals would often tell reporters, including me, that they were “holding their noses” and voting for Trump as a pragmatic matter. He was described as the lesser of two evils, and they were making a binary choice based on policy. This year, as Trump faces criminal charges related to his actions on January 6, 2021, he has escalated his anti-democratic rhetoric, and despite the fact that conservative voters had many other options available in the 2024 Republican primary, evangelicals once again are strongly supporting him.

They seem not only to have made peace with backing Trump despite his character, rhetoric and other behavior in recent years, but in many cases also to have embraced him as a “fighter” for their ideological causes. I tend to agree that’s unlikely to change at this point. Trump was right when he said that he could “shoot someone on 5th Avenue” and his supporters wouldn’t waver. This appears to be true of most of his evangelical supporters.

That said, this iteration of the church appears to be on the decline. Poll after poll indicates white Christianity is shrinking as a proportion of the population, and a growing number of Americans do not align themselves with any religion. Within evangelicalism, much of the growth is coming from Latino congregations and other diverse groups.

But I wouldn’t assume, to be clear, that those younger, more diverse Christians will all be anti-Trump or even politically liberal. I think we’re entering a period of religious realignment that will almost certainly have political implications, although it’s unclear to me exactly what those will be.

GG: I was a boy in a conservative Christian culture, so I didn’t live “as a 17-year-old virgin wearing a purity ring on my left hand” as you describe. It’s taken walking alongside Kristin Du Mez and Beth Allison Barr to truly understand the ways women are maltreated, excluded and even abused in conservative Christian traditions. What does your life and research tell us about the gifts and perils of being female in that sort of purity culture? What advice would you offer girls who are growing up in that culture now?

SM: The evangelicals of my parents’ generation who promoted purity culture had good intentions: they didn’t want their children to get hurt, and they wanted them to have strong, healthy marriages and families. What we’re realizing now as a generation of those of us raised in purity culture have reached adulthood is that the promises of purity culture often rang hollow.

Rather than a set of guidelines or best practices for meaningful connection, they often were experienced as a rigid and oppressive regime of rules and dire warnings about the risks of engaging in a completely normal human activity. Chastity before marriage was marketed as a formula for marital happiness, but the reality didn’t live up to the hype for many evangelicals who found themselves in unhappy marriages, living with overwhelming shame about their bodies and fear of sex, discovering they were gay or lesbian, or simply “waiting” so long that they never learned how to navigate romantic relationships.

As a journalist, I don’t tend to give a lot of advice. But I’ll tell you what I tell my children: Sex is beautiful and healthy and fun, and it also requires a certain level of caution, certainly around prioritizing consent, and emotional and physical well-being.

GG: Many of the Christians you describe in your book are sincere and faithful, but you also point out how over time the truth for evangelicals has evolved to mean “whatever is good for our tribe.” I know the same is true in other communities because I see it in some of mine. Besides writing this wide-ranging book, you also spend a lot of time thinking about and covering the intersections of faith, politics and culture for NPR. We seem divided by ideologies and reality systems, so I wonder: What kind of conversation is possible across those divides? Where are you seeing real conversation and connection taking place?

“Leaving one type of faith doesn’t have to mean leaving all of it.”

SM: The internet is a wild and sometimes messy place, as we know, but it’s also a place for connection and conversation. I’ve been fascinated by the conversations I’m seeing in exvangelical, deconstruction and progressive religious or post-religious spaces. I see people thinking deeply about how to move through the world after leaving the evangelical subculture (and other high-demand religious cultures) and having a lot of thoughtful conversations about what life looks like afterward.

It’s not easy — there’s a sense of grief and loss for many. But I hope people who remain in those religious communities will at least be open to listening.

I think any conversation is possible, if people are willing to engage in it.

GG: As you point out in the book, leaving your faith can be terrifying. You lose a worldview, the truth, your people. But for you, for me, for many of the people you write about, it’s been a key to a more honest life and maybe a more authentic faith. I love David Dark’s lines about how leaving a tradition frees you to engage with faith and with people in a new way. As upset as I remain toward some evangelicals, I am filled with hope by exvangelicals. Where are you finding hope about the state of the church and the state of our nation? What do you hope readers would carry away from The Exvangelicals?

SM: Indeed, leaving one type of faith doesn’t have to mean leaving all of it. Giving up one community can open doors to another. But it can be frightening and overwhelming.

I hope the kinds of conversations I’m seeing play out in public around religion will foster a deeper awareness of the importance of religious pluralism and a commitment to the principles of our Constitution, which was designed — however imperfectly — with religious diversity in mind. There are many people of faith who believe deeply, but also believe people must be free to follow the dictates of their consciences and freely choose if and how to practice a religion. That requires a commitment to preserving democratic principles and institutions that create space for individuals to make those free choices.

I hope people who read this book who’ve wrestled with their own faith in some way will feel seen and understood. And I hope those who are less familiar with evangelicalism will feel they have a deeper understanding of life inside the evangelical world, how many evangelicals see the world, and why religious change can be so difficult for people who feel a sense of incongruity with their religious community.

Greg Garrett

Greg Garrett teaches creative writing, film, literature and theology classes at Baylor University. He is the author of two dozen books of fiction, nonfiction, memoir and translation, including the critically acclaimed novels Free Bird, Cycling, Shame and The Prodigal. His latest novel is Bastille Day. He is one of America’s leading voices on religion and culture. Two of his recent nonfiction books are In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

More from this series:

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Winnie Varghese

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Kaitlyn Schiess

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Russell Moore

Politics, faith and mission: A BNG interview series on the 2024 election and the Church

Politics, faith and mission: A talk with Tim Alberta on his book and faith journey

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jemar Tisby

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Leonard Hamlin Sr.

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Ty Seidule

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jessica Wai-Fong Wong