By Aaron Weaver

April 27, 1994.

That’s the date that South Africa held its first democratic election, forming a multi-racial coalition government and officially doing away with the country’s brutal, five-decade long system of racial segregation and oppression. Nelson Mandela was president and apartheid had been brought to an end. However, the “Rainbow Nation” had a new challenge to confront — one that, 20 years later, it has not adequately addressed: HIV/AIDS.

But 20 years later there continue to be those who see what can and must be done.

Sofi’s story

Among them was an English woman named Sofi and her husband, Robert.

As the AIDS epidemic worsened in the late 1990s, they traveled to South African villages along the foothills of the Drakensburg Mountains, bringing food to AIDS patients who were dying in their homes. They did so at a time when there were no medicines, no antiretroviral regimens available. Sofi and Robert received no payment as they fed and bathed the suffering, helping them to be as comfortable as possible in their final days.

Robert later became sick and passed away, but Sofi stayed, and continued the work. She went door to door throughout the rural Winterton area, assisting those in need with health support and information about finances and government services.

In 2009, Sofi started a permanent community center called Isibani, which means “bring the light” in Zulu. The center offers many much-needed services, including home-based health care, HIV testing and counseling, food and clothing distribution, child and youth projects, adult literacy classes and emergency assistance. Three years later, Sofi launched Isiphephelo (“refuge” in Zulu) which provides a safe and temporary home to vulnerable, neglected and abandoned children.

Over the years, Sofi has seen a lot of death and knows the many faces of despair. She finds herself frustrated often, weary of a broken system that tends to fail the children it is supposed to protect and keep safe.

“The culture is just in such a meltdown,” said Sofi, noting the growing use of drugs among the region’s teens.

Yet, she continues to be present, serving those with HIV/AIDS and showing a big smile when she’s around the children of Isiphephelo.

‘Pilgrim posture’

But she does not serve alone.

For a week in July, the South Africa Ministry Network, a consortium of Cooperative Baptist Fellowship congregations launched in 2009 to work with and support CBF field personnel in South Africa, led a group of 70-plus Baptists on a weeklong mission experience, with participants divided between mission sites in Johannesburg and Winterton.

The network journeyed to the Rainbow Nation with a ‘pilgrim posture,’ said organizer Stephen Cook, senior pastor of Second Baptist Church in Memphis, Tenn, embracing the call of South African theologian Trevor Hudson to make “pilgrimages of pain and hope.”

“The essence of these pilgrimages of pain and hope is that we are not tourists who set out to see the sights of the places we visit,” Cook shared. “Instead, we are pilgrims and we assume a ‘pilgrim posture’ as we approach these experiences.”

Nor do they assume they come with all the answers.

“The pilgrim is one who is ready to be present, who is ready to listen and who is ready to notice where, how and with whom God is working,” Cook said.

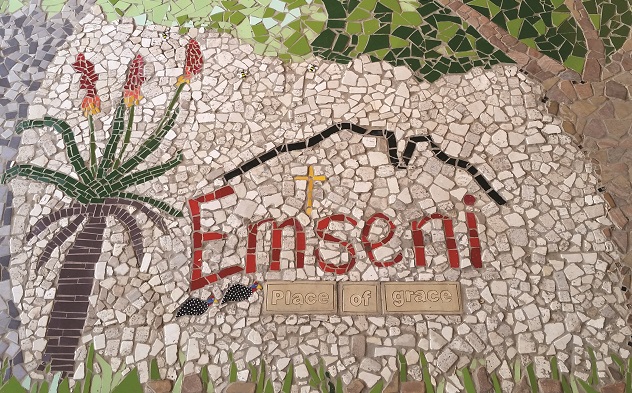

At the Em’seni Camp (“place of grace” in Zulu) outside of Winterton, the network hosted a retreat for Sofi and the children and staff of Isiphephelo. While some played with the kids, others spent time with the staff, leading the group of smiling and singing women in team-building activities, Bible study and providing space for reflection and relaxation.

“I was blown away by these women,” said Thomas Quisenberry, pastor of First Baptist Church in Chattanooga, Tenn., a network member. “I found them to be carrying heavy loads — carrying for the kids of Isiphephelo as well as families of their own.”

Network participants also worked alongside the staff of the Thembalethu Care Organization, a Christian ministry responding to the effects of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the extreme poverty in the region.

Younger generations living in the area, where nearly 80 percent of residents are unemployed, faces intractable challenges, said Betsy Meyer, a field personnel from Seattle’s University Presbyterian Church.

“Even if [youth] go and finish high school, or go to university, there are just so few options for them,” she said. “So, it’s really a struggle. That’s the most significant challenge youth around here face — there’s this kind of hopelessness because they don’t really have options.

‘God is at work’

The impact the HIV/AIDS epidemic has had on the region cannot be understated, said Sara Williams, who alongside her husband, Mark, served as CBF field personnel in Winterton from 2010-2014.

“The HIV/AIDS epidemic and extreme poverty have wreaked havoc on society at large,” said Williams, who accompanied the network on the July mission experience.

“Due to AIDS, you have an adult generation of people that have been lost,” she added. “So, you have the children as the head of households and raising children — children who have not been taught the wisdom of their elders, who have not been taught how to participate and contribute to the community, how to be a family and know right from wrong.”

Despite the grim realities, Williams and the network’s leaders see God’s presence in the Winterton area.

“God is at work through the hands and hearts of these local Christians who are doing the work that no one else wants to do,” she said. “They are holding the hands of outcasts and modern-day ‘lepers.’”