I remember vividly the day that I received my letter of acceptance to The College of William and Mary. While I had unrealistically worried that I would be rejected from every institution to which I ever applied, I suspected, based upon the size of the package, that William and Mary had not wasted so much postage to simply inform me of my rejection.

I remember vividly the day that I received my letter of acceptance to The College of William and Mary. While I had unrealistically worried that I would be rejected from every institution to which I ever applied, I suspected, based upon the size of the package, that William and Mary had not wasted so much postage to simply inform me of my rejection.

In 1833, the now defunct Lane Theological Seminary in Cincinnati, Ohio, sent out admission statements on what today might barely qualify as a scrap of paper. One rather unique statement of admission certified “Mr. James Bradley, a man of colour has been admitted by the faculty to the literary dept of Lane Seminary.”

“For many institutions of theological higher learning, this culture of whiteness remains a problem to this day.”

Beaten by his master on countless occasions, Bradley was a former slave in the state of Kentucky. He worked evenings and nights in order to purchase his freedom for roughly $700. “As soon as I was freed,” he wrote in a brief autobiography published in an abolitionist newspaper, “I started for a free State.” He sought admission to the newly-founded Lane Seminary and claimed the faculty “pitied” his “ignorant” state, granting him admission to the school.

Other institutions of theological higher learning had tenuously admitted men of color into their programs in the period prior to the Civil War. Theodore Sedgwick Wright graduated from Princeton Theological Seminary in 1826, and Jonathan Clarkson Gibbs attended for a year in 1854. Alexander Crummell was rejected from General Theological Seminary because of the color of his skin, but he along with James W.C. Pennington were allowed to attend lectures at Yale Divinity School. Neither Crummell nor Pennington, however, received formal admission to the institution.

Bradley entered Lane Seminary as a part of its inaugural class, but he had to navigate the school quite differently than his white colleagues. While he claimed in his autobiography the students and faculty treated him “much like a brother” and “as if my skins was white,” he recognized that he was not like his colleagues. He did not have the same leverage to openly criticize the institution.

When addressing the circumstances of slavery, he wrote, “The truth is if a slave shows any discontent, he is sure to be treated worse, and worked harder for it; and every slave knows this.” As a result, he explained, slaves showed few signs of discontent. Following this logic, Bradley knew during his time at Lane that he could not show any dissatisfaction for fear that he may be punished or expelled for his behavior.

When seminary students organized a series of debates regarding slavery and abolition in the spring of 1834, Bradley participated, but cautiously. As reports from the debates showed, Bradley chose a tone of “sarcastic argumentation,” and his address received “spontaneous roars of laughter.” When asked whether free blacks would be able to take care of themselves, Bradley sarcastically retorted that it would be strange if they couldn’t considering they were already taking care of themselves and their master and their master’s family.

Bradley calculated that humor could get him farther than a tone of anger or sadness. While his colleagues could express the full range of their emotional dispositions, he could not. Despite his acceptance to Lane, he was a minority of one. The school was still a white space that was not designed to educate or welcome his black body.

The series of debates angered the board of trustees, and ultimately more than 50 students, the vast majority of the school’s population, left. They became known as the Lane Rebels. Bradley was both among them and apart from them. The institutional culture was white, and Bradley had to navigate this culture carefully.

For many institutions of theological higher learning, this culture of whiteness remains a problem to this day.

In September, Virginia Theological Seminary took a significant step forward, moving the institution beyond merely studying and researching the legacy of white supremacy and racism on their campus, by allocating a $1.7 million endowment fund as a means of offering reparations for the sins of slavery. Many slaves built and worked on the seminary’s campus both prior to and after the Civil War.

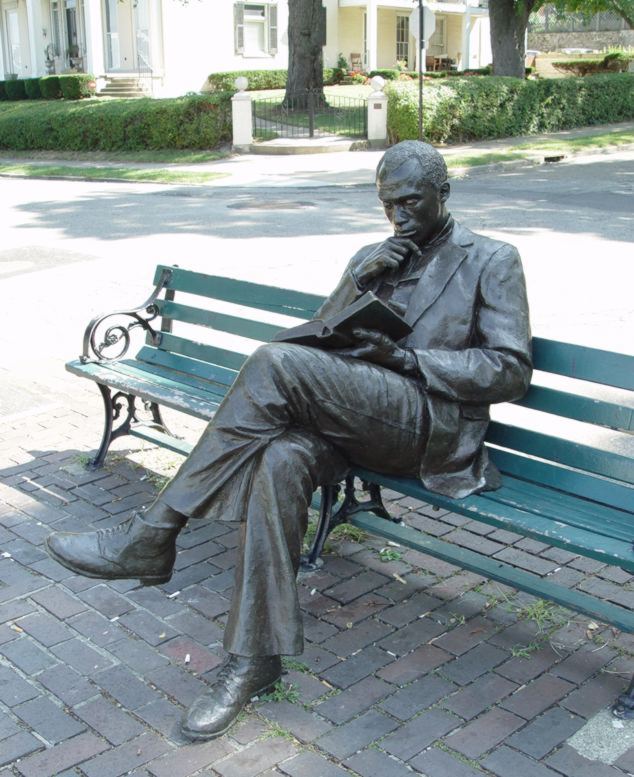

On Oct. 18, Princeton Theological Seminary took steps to seek restitution for the ways it benefited from America’s slave economy. In addition to allocating financial resources for scholarships for decedents of slaves or underrepresented groups, the seminary will hire new faculty members, make changes to the curriculum and rename the library after Theodore Sedgwick Wright.

Both seminaries provide a helpful model for institutions of theological higher learning specifically and religious institutions generally to combat the legacies of white supremacy and to fight for racial justice. Self-studies and historical audits are important and helpful, but only function to identify problematic histories. Such studies must be followed with restitution.

Beyond the importance of monetary reparations, the stories of James Bradley, Theodore Sedgwick Wright, Jonathan Clarkson Gibbs, Alexander Crummell and James Pennington reveal that in addition to money, institutions of theological higher learning must also address their campus culture.

Seminaries and divinity schools emerged in the early 19th century for the purpose of educating white men destined to “settle” congregations across the growing American landscape. These schools were not founded to educate black men, nor were they founded to educate women. Today, converting these institutions into spaces welcoming of peoples from diverse racial, gender or sexual identity backgrounds requires institutional change.

“Beyond the importance of monetary reparations … institutions of theological higher learning must also address their campus culture.”

Such an observation is not novel, and there are many individuals who have devoted their lives to bringing about such institutional change. Churches and countless other social institutions face similar challenges, and there is no simple or singular strategy for confronting these forms of white supremacy.

In some ways, Bradley’s experience at Lane more than 185 years ago can show us how far we have come. But in other ways it shows us how far we have yet to travel. Bradley proposed that “God will help those who take part with the oppressed.” Such a theological proposition continues to be articulated in 20th- and 21st-century liberation theologies.

May America’s white Christian population have the courage to make the sacrifices necessary to “take part.”