Opponents of teaching Critical Race Theory in U.S. classrooms allege that it indoctrinates impressionable students and, worse, makes them feel responsible for past injustices they had no part in. Much time is devoted to such indictments and to efforts to restrict and even ban such teaching.

While we can debate the scholarly merits of Critical Race Theory and its place in the classroom, students do need to think about our collective responsibility for such evils.

Ken Zagacki

Many opponents of Critical Race Theory are Christians, and yet that faith teaches that we bear some collective responsibility for evils committed by others. The evangelical world has endowed Critical Race Theory and “wokeness” with almost demonic power. They have declared it the enemy of the church and democracy.

Yet President Abraham Lincoln acknowledged collective responsibility in his second inaugural address. Even though many (not all) of the northern states had abolished slavery, God had given “to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came,” Lincoln said.

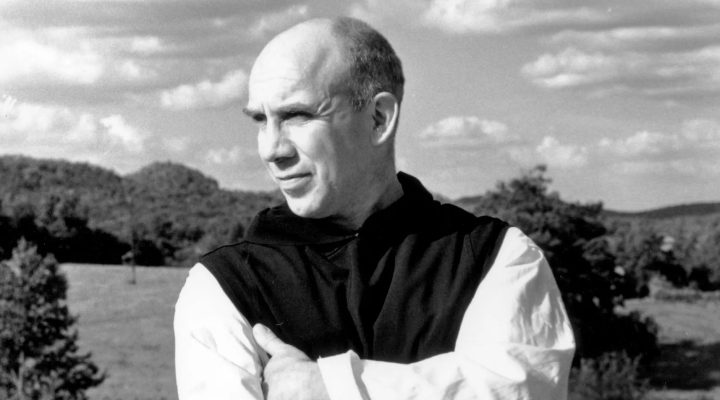

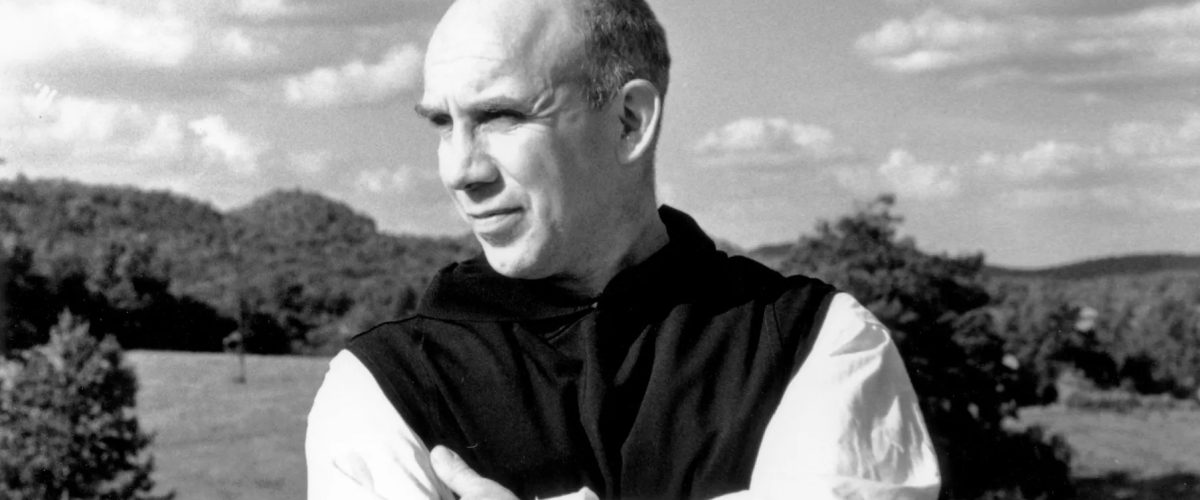

It is productive to consider such issues in light of Christian theology and practice. One important source is the Catholic Trappist monk and social thinker Thomas Merton, who died in 1968 near the end of the Civil Rights movement he hoped Christians would join. Merton was inspired by Martin Luther King Jr.’s April 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail” and prompted by the Ku Klux Klan’s church bombing in Birmingham that killed four young girls later in September. He wanted to confront white people, and for them to confront themselves, with their ongoing complicity in over-privilege and the oppression of people of color.

His thinking about this crucial moment in American history was guided by his understanding of Catholic theology and a more general sense of what he believed constituted a strong moral community. For Merton, a robust moral community was one in which groups of people recognized a common ethical commitment to seek justice, to demonstrate compassion, and to fulfil moral obligations.

Merton’s important insight was that introspection and the experience of collective moral responsibility, however uncomfortable it made one feel, constituted a holy people as a moral community and brought an awareness of God. He believed a moral community whose nature and discipline were capable of hosting the presence of God in the midst of all its society’s difficulties, past and present, would be able to make a space, a house and a home for everyone.

Merton reiterated the criticisms King had expressed about the inaction, condescension and complicity of white people and particularly of white moderates. Like King, he hoped to transform the character and behavior of those white Christians and liberals “so out of touch with the realities of the time that they have no idea how they can effectively help” African Americans.

“For Merton, struggles with the self and with one’s relation to history, as embodied in liturgical practice, were necessary for a moral community.”

In this respect, Merton would have appreciated that the personal and group self-awareness he called for was built directly into Catholic liturgy and Protestant confessionals. At the beginning of every Catholic Mass, congregations are asked to take a moment to consider and seek forgiveness for their sins, where racism is a sin. Protestants, meanwhile, engage in public acknowledgments of sin and prayerful redemption. Undoubtedly, some of the aforementioned critics would find such unsparingly direct self-reflections and public avowals problematic because they open the possibility that people experience dissonance concerning the sins of our shared past.

For Merton, struggles with the self and with one’s relation to history, as embodied in liturgical practice, were necessary for a moral community. The value was found in the self-searching, joined with others in a larger moral community, and in the individual and community action this might produce.

Still, many Christians resist contemplating the possibility of their complicity regarding racism. Many choose to deny it as a genuine problem or its significance as a legitimate issue in public education.

However, one lesson to be drawn from Merton is that a critical accounting of racism in the criminal justice system and in other social structures, as practiced in some race-based education, is morally prudent and religiously obligated — especially if churches shy away from it.

Ken Zagacki serves as professor of communication at North Carolina State University. He earned a Ph.D. in communication from the University of Texas at Austin.

Related articles:

50 years after his death, Thomas Merton’s words haunt us yet | Opinion by Bill Leonard

White hysteria, Critical Race Theory, and eyes that dare not see | Opinion by David Gushee