The one thing everyone who interacted with him seems to agree on is this: Tim Keller was a heckuva nice guy.

So nice, some say, it’s hard to believe he was a conservative evangelical.

So nice, others say, he caved in to the worldly pressures of centrism.

So nice, some say, it’s easy to forget the damage his theology did to women and members of the LGBTQ community.

So nice, others say, his life and ministry should be a model for renewal in the American Christian church.

Tim Keller’s legacy is complicated.

Since his death from pancreatic cancer Friday, May 19, social media and traditional print media outlets have been overflowing with effusive words of praise for the Presbyterian pastor and author. By Sunday evening, the No. 1 trending hashtag on Twitter was #ThankYouTimKeller.

By Sunday evening, the No. 1 trending hashtag on Twitter was #ThankYouTimKeller.

Few pastors in America will trend on Twitter because of their death. Tim Keller was not an ordinary pastor. He was one of the most influential evangelical pastors of the past 25 years — so influential, yet quiet, that even churchgoers who never knew his name likely were influenced by his writing through their pastors.

Matt Cook

“He’s probably the most influential American minister to die since Billy Graham. He’s not in that category but firmly on a second tier of influence and impact,” said Matt Cook, director of the Center for Healthy Churches.

“Theologically, he put a friendly face on Reformed evangelicalism without altering any of its substance. He probably deserves some credit for his theological contributions to apologetics,” Cook said. “He’s the Ben Sasse of evangelicalism. He isn’t a jerk, but he really does believe things that are very conservative.

“Methodologically, though I give him lots of credit. His stuff on vocation is very good. He thought long and hard about how to engage an urban context confessionally and was highly successful. He didn’t create a movement that is tied to him but he cast seeds out widely that will grow in lots of places.”

Well known halfway through life

Keller was not well known nationally until the second half of his ministry life.

Born in 1950 in Allentown, Pa., his family attended a Lutheran church, where he participated in confirmation classes. As a student at Bucknell University in 1968, he got involved with InterVarsity Christian Fellowship. There he became convinced of the truth of Christianity and was influenced by reading British evangelicals such as John Stott, F.F. Bruce, and C.S. Lewis.

In 1972, he enrolled at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, an evangelical school in Massachusetts. From there, he was ordained to ministry in the Presbyterian Church in America, which had been founded only two years earlier. The PCA is a smaller, more conservative denomination than its better-known counterpart, the Presbyterian Church (USA).

At age 24, Keller became pastor of a Presbyterian congregation in Hopewell, Va., south of Richmond. Nine years later, he moved back to Pennsylvania to teach practical theology at Westminster Theological Seminary. He also took on a staff role for the PCA, working on church planting.

In 1989, he tried to recruit someone to start a PCA church in New York City, and everyone turned him down. It was a “fool’s errand,” they said.

Eventually, denominational leaders convinced Keller he already knew the perfect candidate: himself. So he and his wife, with a mixture of faith and trepidation, moved to Manhattan and started Redeemer Presbyterian Church. He was 40 years old.

Their initial goal was to gather up young people who were likely to be unchurched.

Knowing the challenge of such a task, his motto became, “Church as usual will not work.”

Knowing the challenge of such a task, his motto became, “Church as usual will not work.” And yet what he and others created at Redeemer is a highly traditional worship format — with classic hymns and accessible liturgy — accented by Keller’s thoughtful, irenic, engaging preaching.

Still, it was slow slogging.

Daniel Silliman, writing for Christianity Today, picks up the story: “The church saw some success in its first decade. By the end of 1989, there was regular attendance of about 250. In the fall of 1990, the church was attracting 600, including more than a few nonbelievers who were just interested in what Keller had to say.

“The dramatic moment that brought Redeemer to national attention came after the terrorist attacks of 2001 destroyed the World Trade Center. The following Sunday, more than 5,000 people showed up to church. They couldn’t all fit in the space, so Keller promised to hold a second service. Hundreds came back. By the time the city had returned to something approaching normal, Redeemer’s weekly attendance had grown by about 800 people.”

Michael Luo, writing for The New Yorker, adds: “On the fifth anniversary of the attack, White House officials asked Keller to deliver a sermon at an ecumenical service at St. Paul’s Chapel, in Lower Manhattan, for the families of the victims. In 2011, President Obama invited Keller to the White House to speak at the Easter prayer breakfast.”

By this point, Redeemer had grown to 5,000 members and become the hub of its own church planting movement, helping launch 16 PCA congregations and dozens of others with various affiliations. Redeemer also became a multi-campus church. And one of the most unusual features of this multi-site approach is that congregants never knew which site Keller would preach at. The pastor took great pains to ensure people came to worship, not just to hear him.

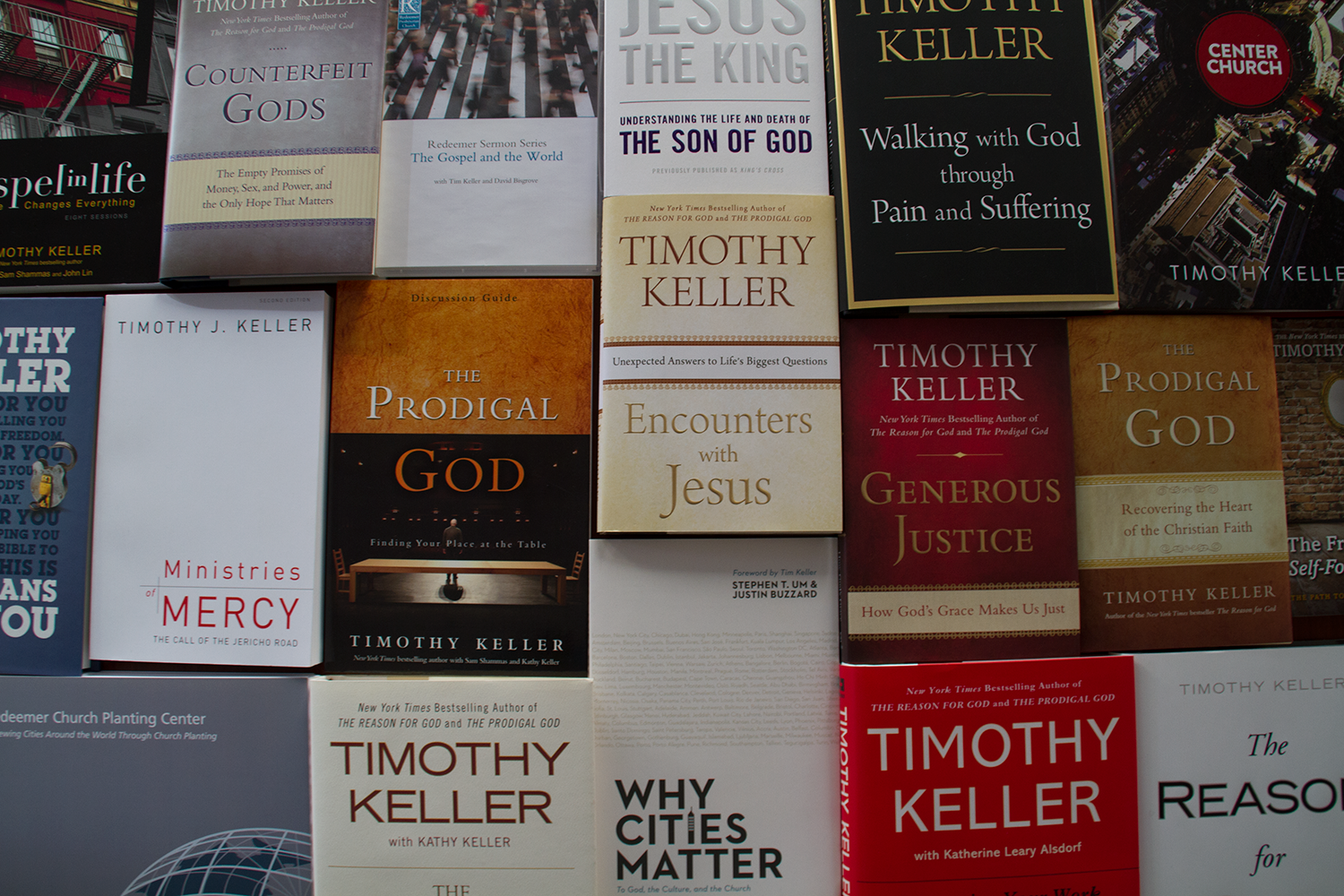

In the late 2000s — only in the last 15 year of his life — Keller began writing books in earnest. His 2008 book, The Reason for God, talked about common objections to Christian faith he heard in New York City. The book reached No. 7 on the New York Times nonfiction bestseller list. He went on to write more than 30 additional books, culminating last year in Forgive: Why Should I and How Can I?

About more than worship

Keller’s legacy at Redeemer was not just about worship, either.

The church founded Hope for New York, a nonprofit that sends volunteers and gives grants to faith-based ministries addressing social needs in New York City; the Center for Faith and Work, to help young professionals find a spiritual calling in their secular vocations; and Redeemer City to City, a church-planting ministry.

In one of the most difficult places in America to start a traditional and conservative evangelical church, Keller did just that.

Observers say he succeeded, in part, because he was kind and gracious and had the spiritual gift of genuinely listening to others.

“The Reformed side of evangelicalism walked away from him in part because he never wanted to frame his convictions in combative ways.”

“The Reformed side of evangelicalism walked away from him in part because he never wanted to frame his convictions in combative ways,” Cook explained. “He talked about that ‘if people were offended, they should be offended by the gospel, not because Christians are jerks.’

“But I don’t think his irenic spirit was primarily a church growth technique. I think it was more an aspect of his theology. He had such a theocentric mindset that it muted any tendency toward overreaction to others — both good and bad.”

Although a Calvinist, Keller was not mean-spirited, Cook added. “There’s tremendous irony in arrogant Calvinism, which unfortunately we see all too often. Keller, on the other hand, seems to have developed some of the humility that ought to come along for the ride with that theological framework. If we consider his lasting legacy, I hope that’s a part of it.”

The Gospel Coalition

Of all the complicated parts of Keller’s legacy, his role in founding The Gospel Coalition in 2005 stands out.

This network of mainly Reformed pastors came to exert significant influence over parts of conservative evangelicalism through publishing and conferences. Over time, TGC took on a more strident tone than Keller ever exhibited. And some of those in the very group he co-founded accused him of being too soft on sin and worldliness.

A primary citation of Keller’s perceived apostacy is an interview he gave in 2011 at an event called The Veritas Forum. Critics contend he did not answer firmly and decisively enough a question about whether Jesus is the only way to God and a question about what happens to unbelievers after death. Most conservative evangelicals — and nearly all Reformed evangelicals — insist on belief in a literal hell as a place of eternal conscious torment.

Tim Keller

A group called The New Calvinists asserts: “Despite Keller’s massive reputation and popularity among evangelical Christians, we maintain that he does not proclaim the historic gospel of truth once delivered to the saints, but a gospel of his own making.”

Yet that rejection did not make Keller any more accepted by progressive Christians because he remained firm and explicit — although kind — in his beliefs in complementarianism (male headship) and against LGBTQ inclusion.

Rejected right and left

The two extremes of Keller’s rejection were illustrated in a few examples — among thousands — of tweets posted about his death and legacy.

Jeff Wright, a Southern Baptist pastor in Middle Tennessee who serves as a trustee of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, said: “Of course Managerial Class Evangelicals are at pains to present Tim Keller as the model of Christian ministerial faithfulness. They are his real legacy as a new Charles Finney — a group of feckless, fashionably pragmatic compromisers.

“Keller was once helpful but ended as a warning to believers about what worldliness can do to a brother of real gifting and usefulness (for a season),” Wright added. “They can lionize him as a model because he, like them, hates fundamentalists and other cultural unfashionables.”

He concluded: “It isn’t OK to make a man who fell in love with the world, despised Christians who didn’t, and who encouraged others to do the same, a lion of Christianity. I am sad for Keller’s family in their loss. I am also sad for what Keller became in his later years — as someone who learned much from him earlier.”

Silliman wrote in Christianity Today: “Keller was frequently accused — especially in later years — of cultural accommodation. He rejected culture-war antagonism and the ‘own the libs’ approach to evangelism, and people accused him of putting too much emphasis on relevance and watering down or even betraying the truth of Christianity out of a misplaced desire for social acceptance.”

On the other hand, Keller was accused of wrapping up hatred in kinder, gentler clothes.

Jo Luehmann, an author and publisher and host of “The Living Room” podcast, tweeted: “Imagine people chose to celebrate the good Mussolini did in Italy, the good King Leopoldo did for Belgium, the good of Trump for the wealthy. That’s how you all sound when you celebrate men like Tim Keller. He caused more harm than did good, regardless of his nice demeanor.”

Keller was particularly criticized for his stance against homosexuality — a view that endeared him to many centrists, was not enough to redeem him with the far right and totally alienated him from the left.

A queer commentator named Matt who goes by the Twitter handle @thesnarkygent, said: “Apparently people are so into Tim Keller they’ll be more angry about seeing him criticized than about the lifelong queerphobic theology he spread, influencing countless Christians in harming queer people in their lives.”

Elsewhere, a reconciler

Yet in other quarters, even among people who disagreed with Keller’s theology, he was remembered as a significant positive influence.

Brandan Robertson, a gay minister who is a columnist for BNG, tweeted: “There’s a lot I disagree with Tim Keller on. But the fact that early on in my faith, he showed that one could be evangelical and thoughtful, intellectual and kind, helped me tremendously on my journey of faith.”

Chris Hutchinson, a PCA pastor in Blacksburg, Va., told how Keller personally encouraged him as a pastor and writer. He concluded: “Keller was singularly gifted in his intellect, productivity and capacity to engage with literally thousands of writers and ordinary people like me. He was first and foremost a pastor, caring for individuals. Most of us can’t come close to his capabilities.”

Trillia Newbell, an author and executive at Moody Publishers, tweeted: “Some repeated themes I’ve seen in our tributes about Tim Keller are that he was approachable, humble, kind, gentle and genuinely interested in others. He was eager to listen. He wasn’t entitled, haughty or proud. I pray we imitate him as he imitated Jesus. That was my personal experience interacting with Tim … . He took real interest in people.”

Influence on urban church planting

One of the unlikely people heavily influenced by Keller’s passion for urban church planting is Fred Harrell, founding pastor of City Church in San Francisco.

Fred Harrell

“It is widely documented that Tim and I had fundamental disagreements on two crucial issues: the inclusion of women in ministry and the affirmation of LGBTQ persons. I have plenty to say about that for another time. Today I’m remembering and honoring his impact on me and the church I founded,” Harrell wrote in an online post.

“His vision to see the importance of bringing gospel ministry to cities was not a popular idea in the late ’80s. His concept of ‘applying the gospel,’ while problematic in some respects, is dynamic in others and has shaped an entire generation of male pastors. His philosophy of ‘preaching to the empty seats,’ which revolutionized how I and countless others communicated, motivated people to invite their friends to church. His concept of ‘a contextualized communication of the gospel’ was made more mainstream and that is still sorely needed in all expressions of Christian faith today.

“His commitment to social justice, while not prophetic enough for many, was still at the tip of the spear in his own tribe, and predictably got him scapegoated by the ultra-right in the PCA.”

Harrell explained: “I was shaped profoundly by Tim Keller. The first time I ever heard him preach was like lightning. I’ve often thought of that day as my ‘vocational conversion’. I never preached another sermon the same way after that one day. It was at the Church of the Advent Hope in 1992. The sermon was on Genesis 3. From that moment, it was evident that I was witnessing the emergence of a preacher who would go on to be regarded as one of the greatest in conservative Christianity. The Chrysostom of his era.

“Tim’s focus was crystal clear: He spoke to the person who wasn’t yet present in the room. He inspired consumeristic Christians to adopt a more missional mindset, inviting them to bring their non-Christian friends without fear of embarrassment. His sermons avoided unnecessary alienation, allowing the message of Jesus to be accessible to anyone. It was a revelation for me and an idea that preachers today would be wise to remember and practice.

“As he liked to say, the gospel critiques every worldview and has something in it to offend and challenge anyone, convinced, unconvinced or otherwise.”

“When Tim came along, typical evangelical churches functioned as factories of confirmation bias, merely reassuring the already convinced of their rightness. Tim turned that model on its head. While he argued for his version of the Christian faith, he also critiqued your own version, particularly if it fell short in the area of practical application. Tim wasn’t afraid of the book of James. As he liked to say, the gospel critiques every worldview and has something in it to offend and challenge anyone, convinced, unconvinced or otherwise.”

Keller influenced Harrell — as he did many other younger pastors — to hear God’s call to America’s cities. Harrell sat down with Keller and Redeemer’s executive pastor and peppered them with questions — captured on a tape recording.

“True to their guidance, I followed their instructions diligently. They provided insights on networking, gathering a launch team, emphasizing the importance of allowing the church’s name to organically emerge from an understanding of the city, the significance of listening to and learning from the city instead of assuming a role as its savior, creating an inclusive space for everyone regardless of their beliefs, and structuring home gatherings,” Harrell said.

A decade later, Harrell left the PCA over the denomination’s stance against ordaining women. Once again, although disagreeing theologically, Keller demonstrated a gracious spirit, Harrell said. That was his last in-person conversation with the man who had been his church-planting mentor.

“There would be no City Church San Francisco if not for Tim Keller. I would have had no idea what to do in San Francisco if not for Tim Keller. While there will be time for a more full assessment of his theology and ministry, the way it helped and hurt like there will be for mine and every pastor, today is a day to honor and remember this unique reflection of God’s image. It is a day to recognize that, just as God has always known him and all individuals, Tim Keller has now come to more fully realize what he so frequently preached: that he is a beloved child of God.”

The Trump era

Whatever rifts existed between Keller and the far-right of evangelicalism and Calvinism grew wider in the age of Donald Trump, according to both Silliman and Luo.

Silliman recalled two common teachings of Keller:

“The gospel is this: We are more sinful and flawed in ourselves than we ever dared believe, yet at the very same time we are more loved and accepted in Jesus Christ than we ever dared hope.”

“A frequent theme throughout his preaching and teaching was idolatry.”

And “a frequent theme throughout his preaching and teaching was idolatry. Keller maintained that people are broken and they know that. But they haven’t grasped that only Jesus can really fix them. Only God’s grace can satisfy their deepest longings.”

In the modern context, some of his critics called Keller a Marxist, Silliman wrote. And even a “high-profile Marxist who is particularly effective at repackaging Marxism for a Christian audience.”

He added: “When Keller argued that orthodox Christians should not embrace one political party in America’s two-party system, some said he deeply misunderstood the way the culture had changed. The ‘winsome’ approach wouldn’t work in a world that was already deeply hostile to Christian truth, they argued.”

Luo, the New Yorker reporter, ended up attending Redeemer Church and got to know Keller better through the years. He described Keller as “perhaps the most gifted communicator of historically orthodox Christian teachings in the country.”

Luo recalled an op-ed Keller wrote for The New York Times warning about aligning Christian faith with any political party.

“Most political positions are not matters of biblical command but of practical wisdom,” Keller wrote. “Should we shrink government and let private capital markets allocate resources, or should we expand the government and give the state more of the power to redistribute wealth? Or is the right path one of the many possibilities in between? The Bible does not give exact answers to these questions for every time, place and culture.”

In the age of evangelical Trumpism, that was not a sufficient answer to satisfy right or left.

Keller is survived by his wife, Kathy, and their three sons, David, Michael and Jonathan.

Related articles:

Tucker Carlson takes on Russell Moore, Beth Moore, Tim Keller and David French

Tim Keller wants us to talk about forgiveness