“Thank you for the tour. Your church has such an interesting history. I was surprised that you didn’t mention God.”

What? Really? That can’t be right.

Telling a church’s story seems simple. You just tell what happened. Start to do that, however, and you discover it is not easy. What do you tell? What do you leave out? How do you describe who you are and how you got that way? The challenge is not knowing the facts but understanding what they mean.

Brett Younger

One way to tell a church’s story is with the church as the hero. Who doesn’t enjoy patting themselves on the back?

Sometimes my congregation, Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, tells our story that way: “In the middle of the 19th century, we saw that slavery was a scourge on our country and decided to end it. Henry Ward Beecher, our first senior minister, was a famous abolitionist and a friend to Frederick Douglass. We courageously assisted freedom seekers through ‘The Grand Central Depot of the Underground Railroad.’ We invited Abraham Lincoln to speak and helped him become president. We fought for women’s suffrage and civil rights. Martin Luther King Jr. preached an early version of his ‘I Have a Dream’ sermon at Plymouth. The church is successful because we’re strong and smart. We’re proud of our story.”

Talking about your achievements is fun, but it feels arrogant.

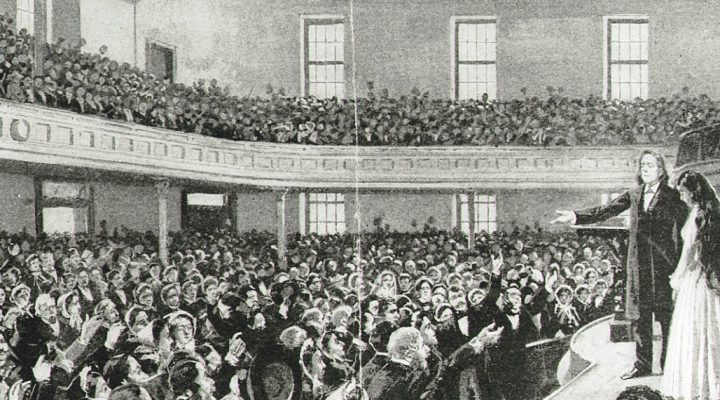

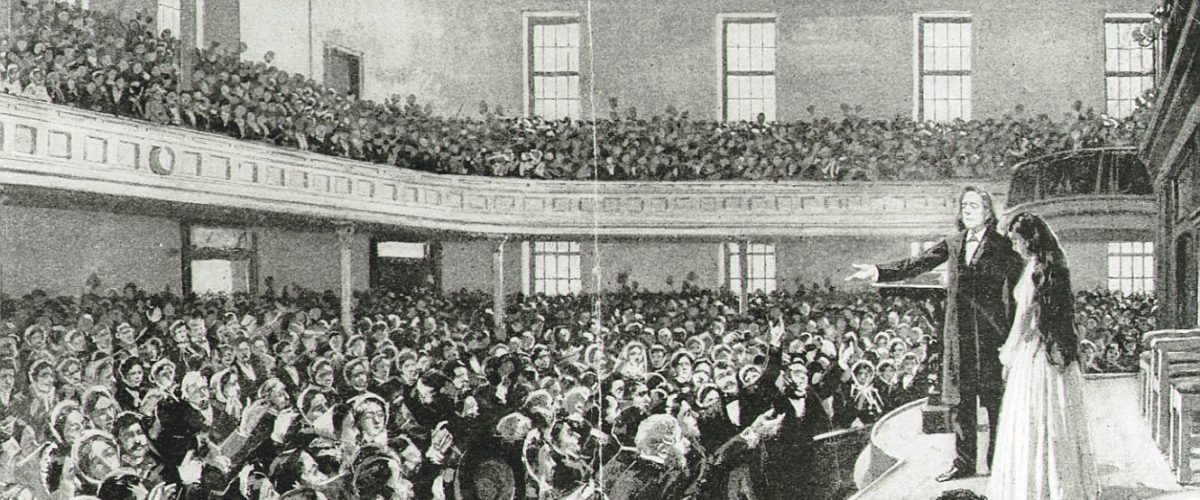

A second option is to tell the church’s story without it meaning much: “In the 1840s, some rich businessmen thought it would be nice to have another Congregational church in our neighborhood, which fortuitously turned into America’s first suburb. They stumbled on to Henry Ward Beecher, who was having a hard time in Indiana, as the first senior minister. Henry knew how to draw a crowd. Beecher’s theatrics filled the 2,000-seat sanctuary twice each Sunday for 40 years. Lots of famous people have visited our church — Harriet Beecher Stowe, Mark Twain, Charles Dickens, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Susan B. Anthony, Hillary Clinton, Mary Louise Parker, Adam Driver. We’ve been lucky.”

“We have to talk about God’s providence in order to tell the whole truth.”

If we see our church’s history as random events or as the product of our own hard work, then we have missed the point. Ours are the stories of what God has done, sometimes in spite of us. We have to talk about God’s providence in order to tell the whole truth.

We have to incorporate the bad times as well as the good to present an accurate account of God’s care: “In 1847, 21 transplanted New Englanders founded Plymouth Church. They wanted to proclaim freedom of all God’s children, but some also were angry at their last minister. This was the third Congregational church in Brooklyn, not far from the second Congregational church, but the Spirit was at work. Those Christians fought against slavery as agents of God’s justice, although they had attitudes about race that would be embarrassing today. Abraham Lincoln attended Plymouth twice. He came with a sincere desire to worship God and garner votes. Plymouth’s first minister was Henry Ward Beecher, a speaker gifted by God to preach grace and love. In 1875, a history of rumored extramarital affairs caught up with Beecher. Maybe the legal system and the church were right to exonerate Beecher. Probably not. Rev. Dwight Hillis both defended the Klan and gave the commencement address at Howard, a Black university. Rev. Wendell Fifield prayed with a member of Plymouth, Branch Rickey, before Rickey invited Jackie Robinson to integrate baseball. The congregation has always been made up of imperfect Christians who try to understand where God is leading. Each Sunday for 175 years the church has gathered to confess their sins, give thanks for forgiveness, and ask God to make them better Christians. God does remarkable things with flawed followers.”

“Our ancestors in the church are as complicated as we are.”

Our ancestors in the church are as complicated as we are. We should not admire them unthinkingly or enjoy making a list of their mistakes. We should be honest when the church falls short and celebrate when the church follows Christ. Telling the story truthfully helps us see not only where God has led, but where God is leading.

If we sift through our history, we find the insistent presence of hope. If we tell the church’s story without mentioning God, then we have gotten the story wrong.

Brett Younger serves as senior minister at Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, N.Y.

Related articles:

Amid its own racist history, United Methodist Church unites against racism

Teach Baptist history and Bible history to debunk Christian nationalism, historians say

Think U.S. politics is crazy? Check out church history | Opinion by Rhonda Abbott Blevins