In America’s religious landscape, the groups attracting the most public attention are those staking out the poles in our political divides: the shrinking, aging, but still influential group of white evangelicals on the right vs. Black Protestants and the growing religiously unaffiliated cohort on the left.

With the media, political and philanthropic spotlights all focused on the edges, however, America’s important religious middle remains in the shadows.

To be sure, the religious groups at the poles powerfully demonstrate the eye-popping levels of political polarization in the country. In the 2020 election, according to the 2020 Pew Validated Voter Study and the 2020 AP Votecast Exit Poll, 84% of white evangelicals voted for Donald Trump, while 71% of religiously unaffiliated voters and 91% of Black Protestants voted for Joe Biden.

You also can see the political chasms in the religious landscape on hot-button issues such as abortion and immigration:

- Three quarters (75%) of white evangelical Protestants say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases; by contrast, 70% of Black Protestants and 82% of religiously unaffiliated Americans believe abortion should be legal in all or most cases.

- Nearly three quarters (74%) of white evangelicals, compared to only about one quarter of Black Protestants (25%) and religiously unaffiliated Americans (23%), favor extreme measures at the U.S. border, such as “installing deterrents such as walls, floating barriers in rivers and razor wire to prevent immigrants from entering the country illegally, even if they endanger or kill some people” (PRRI, American Values Survey, 2023).

These divides are troubling. And they are important for understanding the democratic challenges we are facing. But they are not the entire story.

On the right, after steep declines over the last two decades, white evangelical Protestants today comprise only 14% of the U.S. population and 19% of 2020 voters. On the left, Black Protestants have been holding steady at 8% of both the population and voters, while the growing group of religiously unaffiliated Americans has ballooned to 27% of the population and 25% of voters.

These groups anchoring the right and the left, combined, account for only about half the country (PRRI, American Values Atlas, 2022).

Among the groups comprising the remainder of the religious landscape, the political divides are less lopsided.

“In this neglected religious middle, there are three groups whose partisan and ideological divides are the most balanced.”

In this neglected religious middle, there are three groups whose partisan and ideological divides are the most balanced: white Mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (14% of the population and 15% of 2020 voters), white Catholics (13% of the population and 14% of voters), and “other race Protestants” (6% of the population and 4% of voters).² These groups all lean Republican, but not overwhelmingly so; they each supported Trump over Biden in 2020 by slightly less than a 60-40 percent margin.

Across a number of measures, you also can see the ways in which these groups are cross-pressured and look significantly different from the white evangelical Protestants to their right. They don’t fit comfortably into left-right stereotypes. (Note: In the analysis below, I cite data for Hispanic Protestants, who represent the largest subgroup in the composite “other race Protestant” category).

- Trump and the Big Lie. While just under six in 10 of each group supported Trump in the 2020 election, majorities of each nonetheless reject the idea that the election was stolen from Trump (59% of white Mainline Protestants, 59% of white Catholics, and 56% of Hispanic Protestants). By contrast 60% of white evangelicals believe the Big Lie that the 2020 election was stolen from Trump.

- Political ideology. While a plurality of both white Mainline Protestants and white Catholics identify as conservative, more than one-third identify as moderate and about one in five identify as liberal. Among Hispanic Protestants, equal numbers identify as conservative or moderate (about four in 10 each), and one in five identify as liberal. Among white evangelical Protestants, seven in 10 identify as conservative.

- Abortion. Nearly two-thirds (65%) of white Mainline Protestants and 59% of white Catholics say abortion should be legal in all or most cases. Hispanic Protestants are more divided (46% legal vs. 53% illegal in all/most cases) but look significantly different than white evangelical Protestants, among whom only 24% believe abortion should be legal in all or most cases.

- Same-sex marriage. About three-quarters of white Mainline Protestants (77%) and white Catholics (73%) favor allowing same-sex couples to marry legally. Hispanic Protestants are divided (50% favor vs. 48% oppose) but considerably more supportive than white evangelicals (36% favor).

- Immigration. Majorities of white Mainline Protestants (56%) and white Catholics (55%) believe the growing number of newcomers from other countries threatens traditional American customs and values, compared to only 32% of Hispanic Protestants. At the same time, however, about six in 10 white Mainline Protestants (59%) and white Catholics (58%), along with two thirds of Hispanic Protestants (66%), favor a policy that would provide a path to citizenship for immigrants currently living in the U.S. illegally. On both of these measures, there is significant daylight between these center-right groups in the religious middle and white evangelical Protestants, among whom seven in 10 say newcomers threaten American culture and only 45% support a path to citizenship.

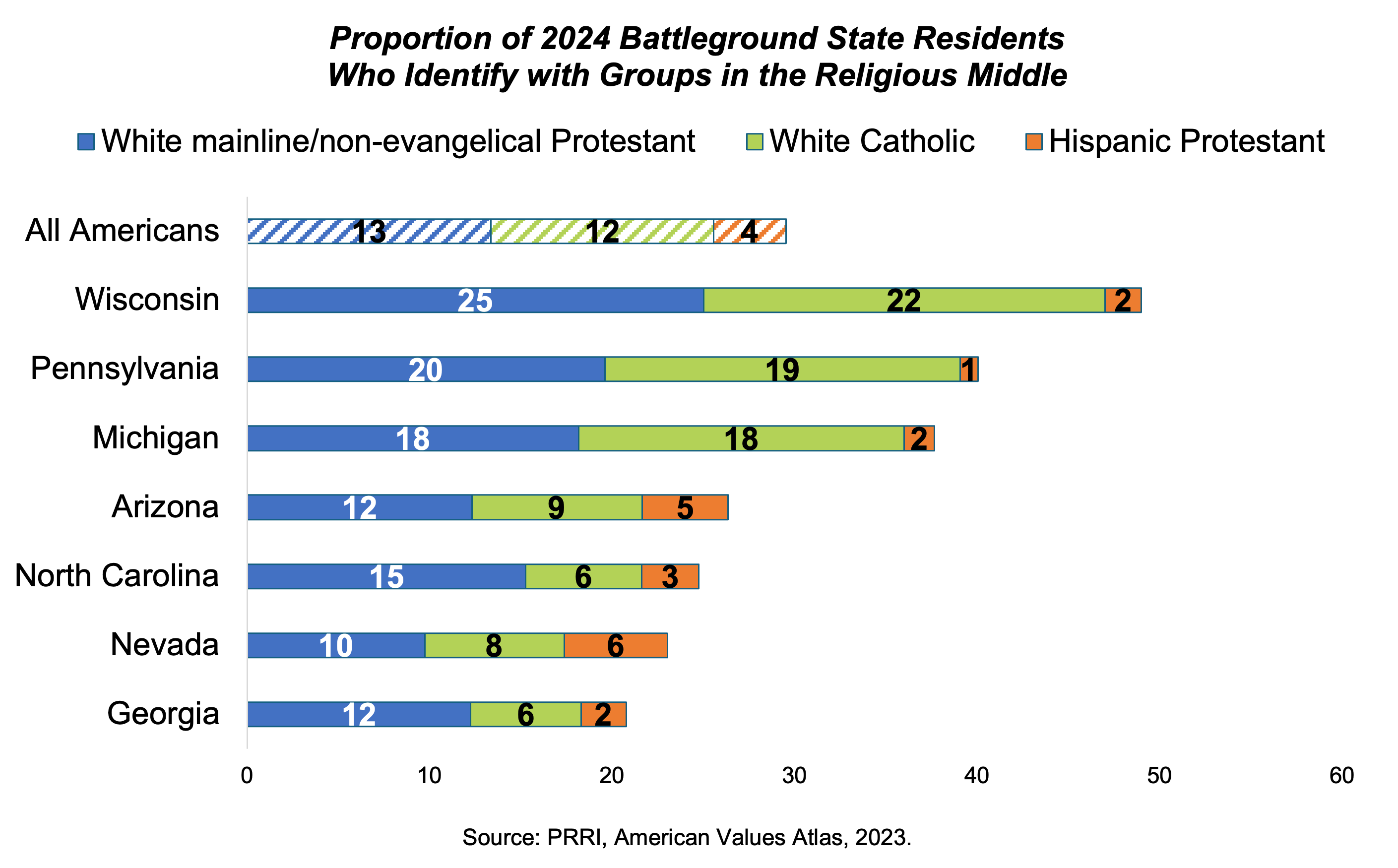

These groups in the overlooked religious middle are also poised to play an outsized role in determining the outcome of the 2024 presidential contest. In the Rustbelt battleground states, the religious middle groups comprise about four in 10 or more of the state’s residents. Notably, in Wisconsin, they represent nearly half the population.

Across the Sunbelt battleground states, groups in the religious middle are smaller but nonetheless comprise one-fifth to one-quarter of the population. While Hispanic Protestants remain a small proportion of Rust Belt states, they comprise 5% of Arizona residents and 6% of Nevada residents — enough to make a difference in a tight election (Reminder: In 2020, Biden won Arizona by only 10,457 votes and won Nevada by only 33,596 votes). Notably, in five of the seven battleground states (with the exceptions of Georgia and North Carolina), white Mainline Protestants alone outnumber white evangelical Protestants.

Historically, dramatically more resources have been marshaled to understand, engage and mobilize the groups on the ideological poles of the religious landscape. In tight elections, like the 2024 presidential race, base turnout always takes precedence in campaign strategy.

But even using this short-term instrumentalist lens, if one is looking for ways to move the needle with a persuasion campaign, outreach to these religious middle groups almost certainly will yield a higher return on investment than efforts among more locked down groups like white evangelical Protestants.

It’s tempting to interpret the contentious disagreements, clergy-laity tensions, and what seem like contradictory co-existing attitudes as a negative attribute. And indeed, the cleavages within the groups in America’s religious middle are plainly visible:

- Many white Mainline Protestant denominations — most recently the United Methodist Church — have been roiled not only by debates over the morality of same-sex relationships but by contentious debates over their own historical complicity with white supremacy. Their churches house a challenging clergy-laity gap, with clergy generally more liberal than their congregants.

- White Catholics are largely supportive of abortion rights and marriage rights for LGBTQ people, in direct contradiction to official church teachings. They also are experiencing tensions between the more progressive leadership of Pope Francis abroad and the more conservative bent of the U.S. Catholic Bishops at home.

- Hispanic Protestants are a small but growing, and increasingly complex, group. They are more conservative on cultural issues, but their ties to family and friends who have immigrated to the U.S. inoculate them against the worst of Trump’s xenophobic appeals. Their theological ties to white evangelicals on the right provide inroads for some of the apocalyptic and authoritarian MAGA appeals. But they also prioritize economic issues like health care, education and rising costs of everyday items above culture war issues.

But in our era of polarization, the disagreements that remain alive in America’s religious middle should be seen as a virtue. Amid the hyper-polarization plaguing our nation, we should be looking diligently for institutions that hold us together, not just in comfortable agreement but in good faith debates.

If we take the long view, with our eyes fixed on the goal of a healthy democracy, we’ll refocus our attention toward these groups in the neglected religious middle, where denominations and pastors and churches are struggling, however imperfectly, to hold people in community across partisan and ideological lines.

Robert P. Jones

Robert P. Jones serves as president and founder of PRRI and is the author of The Hidden Roots of White Supremacy and the Path to a Shared American Future and White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity, which won a 2021 American Book Award.

This column originally appeared on Robert P. Jones’s substack #WhiteTooLong.

Related articles:

Just the facts on abortion attitudes | Analysis by Robert P. Jones

Most independent voters don’t believe presidential election will change their lives

Americans are not equally divided on culture wars, Robert Jones explains in BNG webinar