A tumultuous January is nearing an end, but for many United Methodists the focus is still on Christmas – a proposal for the church’s future named the “Christmas Covenant” that its organizers call “a gift of hope” for the beleaguered denomination.

The Christmas Covenant was drafted in December 2019 following nine months of tempestuous United Methodist events:

- First, a special February 2019 session of the UMC’s General Conference, its global legislative assembly, voted to tighten severely the church’s bans on same-sex marriages and ordaining LGBTQ clergy.

- Those actions sparked a wave of rebellion in May, June and July by the U.S. units known as annual conferences; nearly three-quarters of annual conferences rejected the tightened bans.

- That fall, threats of secession by some factions led an ad hoc group of church leaders to negotiate an amicable parting of the ways called A Protocol of Reconciliation & Grace through Separation.

Concurrent with the Protocol’s negotiations in the United States, and very much under the radar of most American United Methodists, church leaders in regions outside the United States were formulating a different kind of plan. Instead of splintering the 11-million-member denomination into smaller parts, representatives of regions known as Central Conferences looked at ways to loosen some of the ties that bind United Methodists together in hopes of keeping the church unified. That is spelled out in the Christmas Covenant.

Ironically (some would say providentially), Protocol negotiations and the Christmas Covenant’s drafting both reached fruition in December 2019. While the Protocol was unveiled to great fanfare, backed in part by the political clout and money of U.S. conservatives, the Christmas Covenant had a more modest debut.

While the Protocol was unveiled to great fanfare, backed in part by the political clout and money of U.S. conservatives, the Christmas Covenant had a more modest debut.

Only after the Philippines Annual Conference-Cavite approved the Christmas Covenant and its legislation, thus sending it on to the General Conference, did most rank-and-file United Methodists become aware of it. Now there’s a substantial website to explain the proposal, including translations of the Christmas Covenant legislation available in French, Kiswahili, Portuguese, Russian and Tagalog as well as English.

While seen in some quarters as a counterbalance to the Protocol, Christmas Covenant proponents say the two aren’t in opposition to each other.

“The Protocol is an amicable separation proposal,” explains the Christmas Covenant FAQ. “ The Christmas Covenant is about the future of a vital UMC engaged in effective mission work rooted in mutuality, interdependence and respect for the missional contexts of each region it seeks to establish.”

Momentum for both the Protocol and the Christmas Covenant slackened when the scheduled 2020 General Conference was postponed to 2021 because of the coronavirus pandemic. Now that General Conference organizers have decided not to re-open the legislative process for new proposals, efforts to convince General Conference delegates to approve the Christmas Covenant have picked up steam again.

Since early December 2020, proponents of the Christmas Covenant have been posting videos on YouTube to explain the proposal and encourage support for its legislation slated to come before the United Methodist General Conference later this year. The 14 videos posted thus far feature United Methodists from every region where the denomination is currently active: the Philippines, Africa, Europe, and the United States. In keeping with the proposal’s international origin and goals, video hosts make presentations in German, Portuguese, Congolese French, and Filipino Tagalog as well as English.

In various ways, the videos highlight the three guiding principles behind the Christmas Covenant listed on its website:

- Respect for contextual ministry settings.

- Connectional relationships rooted in mission.

- Legislative equality for regional bodies of the church.

Emma Cantor

In the most recent video, deaconess Emma A. Cantor of the Philippines explained that she views the Christmas Covenant as a way to get past the colonialism that has kept The United Methodist Church an American-centric denomination since its founding in 1784.

“Our church serves people in regions that struggle from the legacy of colonization,” Cantor said. “When there is no equity in the church, we create second-class citizens.”

Cantor said she supports the Christmas Covenant because it “creates regional conferences with the authority to further the church’s mission by responding to local needs. It lifts the Central Conferences from the margins.”

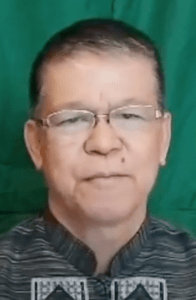

Bishop Ciriaco Francisco

Filipino Bishop Ciriaco Francisco of Manila, who chairs the UMC’s standing committee on international matters, said he supports the Christmas Covenant because it enhances equality among all parts of the church.

“Central Conferences sometimes feel separated from the global United Methodist connection because of different languages, different political structures and lack of communications,” said the bishop. “Knowing that most of our resources are not located in Central Conferences contributes to this sense of being second-class citizens of the church. The Christmas Covenant … seeks to create regional structures built on legislative equality and respect for contextual ministry settings.”

Bishop Francisco also addressed indirectly one of the fears expressed about the Christmas Covenant — that it would impose LGBTQ acceptance upon regions of the church where same-sex practice and other minority sexual relationships are culturally taboo or even illegal.

“No region would be forced to do anything it doesn’t want to do,” the bishop said.

Hilde Marie Movafagh

Hilde Marie Movafagh, a clergywoman who directs the United Methodist seminary in Oslo, Norway, said in her video that she finds it “really strange” that international delegates get to decide ministry and mission issues that are unique to the U.S. church.

“The U.S. has no place to discuss American policies and strategies, so those issues wind up at the General Conference,” said Movafagh. “Regional equality would also give the United States freedom to make decisions fit for its region. We want to be the church in the best way possible in the context where we belong.”

More videos are expected to be posted as the 2021 General Conference approaches Aug. 29-Sept. 7. Much uncertainty remains about how and whether General Conference can meet this year because of the worldwide coronavirus pandemic. Should the conclave occur, the Christmas Covenant will be a major topic of consideration for the 800-plus delegates who will decide The United Methodist Church’s future.

Cynthia B. Astle is a veteran journalist who has covered the worldwide United Methodist Church at all levels for more than 30 years. She serves as editor of United Methodist Insight, an online journal she founded in 2011.