Kathryn Freeman, a writer, speaker and former public policy director for the Texas Baptists Christian Life Commission, said she understands why some Americans are uncomfortable with immigration.

Kathryn Freeman

“It’s hard. I get it. I’m from Texas. I want to know what the little ladies in my local taqueria are saying about me when I get my tacos,” Freeman said in a video presented by Women of Welcome, a Christian ministry dedicated to promoting compassionate laws for and treatment of immigrants and refugees.

But Freeman said neither she nor any other American should let cultural barriers stand in the way of welcoming immigrants into the U.S. “I also know that the language differences, or their willingness to adopt my language, should not determine whether I am for their flourishing.”

Freeman’s presentation explored the influence of race, ethnicity and religion in shaping American immigration policies throughout U.S. history. Her message comes at a time when nativist, white supremacist and nationalist movements increasingly seek to limit citizenship to white Christians.

“From its earliest beginnings, our country has been asking who and what makes us citizens.”

“From its earliest beginnings, our country has been asking who and what makes us citizens. The Constitution did not originally define who is a citizen, but it did give Congress the ability to determine the criteria for citizenship,” she said.

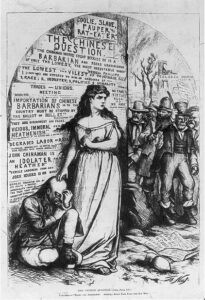

1871 cartoon “The Chinese Question”

Chinese immigrants were targeted early in the 1800s by newspaper editorials and municipal ordinances. “Editorial writers for the San Francisco Chronicle extolled cheap Chinese labor but refused to accept Chinese immigrants as citizens,” she noted.

Freeman presented an excerpt from one editorial arguing the exclusion of Chinese immigrants “is necessary to the settlement of California and the Pacific Coast with Americans and the maintenance of an Anglo-Saxon civilization.”

Newspaper and popular reaction was no more favorable when the first wave of European immigrants arrived from Ireland and Germany between 1820 and 1860, she added. “These immigrants were primarily Catholic, and they were greeted by a wave of anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic sentiment.”

Those sentiments also were based on ethnic stereotypes about immigrants. “In 1856, a local newspaper, The Richmond Whig, published an article condemning Irish immigrants. The article said that all the Irish seek to do is ignore the laws of the United States and utilize the freedom of the United States to drink all the whiskey they can possibly find. To the Richmond Whig, the only way to fix the problem was for the United States government to focus on ‘true Americans’ rather than immigrants who would abuse the rights of natural born citizens.”

The article said that all the Irish seek to do is ignore the laws of the United States and utilize the freedom of the United States to drink all the whiskey they can possibly find.

Race also played a factor early on and was used to exclude freed slaves from citizenship, she continued. “African Americans who were brought to this country as slaves did not become eligible for citizenship until the passage of the 14th Amendment (in 1868). Native Americans did not acquire citizenship upon birth until 1940, thus the most basic tenet of American citizenship law did not apply to all racial minorities until 1940.”

Chinese were targeted again in 1882 with the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned Chinese immigrants and was later expanded to exclude all Asians.

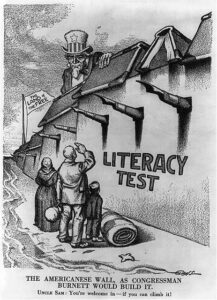

“This sort of nativism continues into the 1920s when new immigrants began arriving from Eastern and Southern Europe from countries rocked by revolution and communism,” Freeman explained. “Southern and Eastern Europeans were thought to be inferior culturally to Western Europeans. One U.S. government report stated certain kinds of criminality are inherent in the Italian race and that the high rate of illiteracy among new immigrants was due to inherent racial tendencies.”

Faith-based discrimination also continued strong during this period: “The resurgent Ku Klux Klan attempted to close all Catholic schools in Oregon because they thought they were anti-American.”

Faith-based discrimination also continued strong during this period: “The resurgent Ku Klux Klan attempted to close all Catholic schools in Oregon because they thought they were anti-American.”

Further, a nativist sentiment “culminated in the National Origins Act of 1924, which set strict immigration quotas based on nationality. The act was designed to limit immigrant populations as much as possible to only Western and Northern Europeans. Other nationalities and ethnicities such as Jews, Italians and Greeks were subject to strict caps. In declaring his support for the law, President Calvin Coolidge declared America must be kept American.”

The act was designed to limit immigrant populations as much as possible to only Western and Northern Europeans.

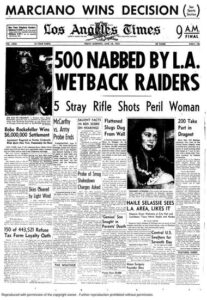

The system of using racial quotas in immigration was modified in 1965 with passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act, which opened immigration to those from Africa, Asia and the Middle East and created a preference for refugees. But at the same time, the measure also limited immigration from Latin American nations.

“Even with those changes in the law, we still have a tendency sometimes to think about immigration in a racialized way,” Freeman said. “I’m from Texas, and the tendency is to think of immigrants as only from Latin and South America. But actually, in Texas we have a huge Indian American immigrant population, and Texas is home to the second largest population of Vietnamese people outside of Vietnam. But even so there are those — and there have always been those — who would exclude others from our country based on race and ethnic background. There are also those who would extend welcome to any and everyone.”

Recent polling has demonstrated that Americans can be of two minds when it comes to immigration. Some research has shown that most voters want Congress to work across party lines to provide pathways to citizenship for undocumented immigrants brought into the country as children, along with protections for migrant laborers and farm workers. On the other hand, another recent survey found overall displeasure with the White House decision to end Title 42, which allows the deportation of asylum seekers from the U.S.-Mexico border without due process due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We have always had two strains running through our American consciousness around immigration: welcome and nativism,” Freeman said. “’What does it mean to be an American?’ is a question we have been asking since our country began, and the answer has changed based on race, nationality and religion.”

“We have always had two strains running through our American consciousness around immigration: welcome and nativism,” Freeman said. “’What does it mean to be an American?’ is a question we have been asking since our country began, and the answer has changed based on race, nationality and religion.”

Freeman argued that the answer should be filtered through the Gospels, and specifically through Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan.

“To be a good neighbor is to cross ethnic boundaries, language boundaries, cultural boundaries, to risk position, prestige and maybe even your life to lift the beaten, bruised and marginalized for a fuller life in Christ,” she said. “The radical love of Christ you and I are called to … does not support a hierarchy of race or ethnicities. It does not support embedding within our democracy the idea that one culture is superior to another.”

Related articles:

Majorities of all Americans want something Congress refuses to do: Meaningful immigration reform now

Once again, immigration reform gets kicked to the curb by Senate

End of Title 42 is popular with immigration advocates but not so much with voters