Snowed in with my family over the Martin Luther King Jr. Day of Service, I stole a few moments away to read and reflect on racism in American society, how it persists even as its forms change, and ways to participate in its undoing. Like so many inspirational figures in human history, King’s message and memory have been grasped and used in numerous ways, toward many ends, by a fairly surprising variety of people. Everyone likes to have a little MLK in their pocket, to think of themselves as defending his legacy.

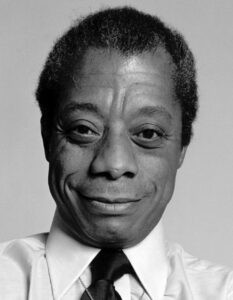

But I must confess that my mind drifted from King toward another great American crafter of words and social critic, James Baldwin. Setting out to read his essay titled “Nothing Personal,” I found a particular thread tangling me up. After telling the story of a personal encounter laden with racism, Baldwin names our fear (as humans, but especially as Americans) of revealing ourselves. Instead, we hide our innermost selves within the sure-as-cement walls of an attitude — a worldview, we might say—that we project toward the world.

(123rf.com)

When we see or even encounter one other, these attitudes tower like the walls of labyrinths to hide and protect our selves within. Yet not only do these mazes distance the self from others and create obstacles between us, but their first job is to hide our honest-to-God, fallible, vulnerable nature from ourselves. With faith in the attitude we project toward the world, we look even upon our “selves” from within the certainties of this worldview.

We even secure our identity through the committed conservation of such an attitude about and in and toward the world: This is who I am and what I am about. And this posture, whether we are aware of it or not, helps us avoid the risks of genuine openness to others or entertaining their good-faith inquiries about our attitude.

Were the walls to drop, were we to encounter other persons without depending overmuch on a fixed attitude, they could expose real concerns — ranging from incoherence and inconsistency to causing or perpetuating real-world harm to others. And repentance, change, growth might become real possibilities.

In this article, drawing near the end of my series introducing the hypothesis of my book, Baldwin’s essay serves as an entry point into the struggles we have with really revealing ourselves, engaging in self-reflection and entertaining others’ perspectives. Somewhat unexpectedly, key themes in “Nothing Personal” connect with Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s analysis of the fallen human condition as it pertains to the most basic failure of world-viewing.

We will leave off today with Bonhoeffer’s description of the fall, in hope that the living, biblical, historical Jesus might free us from our labyrinths. But even here, we may at least begin to envision a new posture — a theological and spiritual alternative to the worldview battle that holds us captive.

The heart of the problem

We struggle to reveal ourselves, as Baldwin describes, at least partly because we are (whether consciously or not) trying to protect ourselves from our own insecurity, confusion and pain. And this burden is made immeasurably lighter by the discovery or invention of an “outsider” who can be saddled with responsibility for upsetting our inner peace. An outsider is a second layer of the self’s defense against the self and any acknowledgment of the troubles within.

James Baldwin

Feeling secure in our attitude, we can locate the threats to our peace exclusively outside the self, especially in those who belong to another worldview, another “people.” Rather more dreadfully, we also might assign blame to those wolves in sheep’s clothing who claim to share our identity yet persist in dissent, trouble our sense of security and strain our selves, which hope not to be exposed. In either case, “once he is driven out — destroyed,” Baldwin writes, “then we can be at peace: those questions will be gone. Of course, those questions never go, but it has always seemed much easier to murder than to change.”

These words fell on my heart like a ton of bricks. And I mourned over the almost unbelievable shallowness of so many visible Christian leaders and thinkers who seem incapable of self-reflection, of receiving genuine criticism, of responding as a person rather than as a proxy for this or that position — an idealized worldview.

Among those who are, in fact, committed to following Jesus, what is the risk in humbly and patiently searching out the truth? In asking whether we might, in fact, have been thinking and doing something wrong? Are we not called to ongoing repentance and transformation?

Baldwin’s statement about the seemingly easy choice between murder and change leads us right to the most basic failure at the heart of worldview theory: the posture it generates in its adherents. A worldview seems to provide a secure foundation for life in this world, a way to confidently understand the self and others — even outsiders — and simultaneously produces a hedge of protection around our fallible and insecure selves, dispelling all criticism and any reason for doubt. Any change we need is only to better conform our actions to the worldview we already hold.

Baldwin’s statement also sounds remarkably similar to Bonhoeffer describing the situation in which the living Jesus finds each of us. So, let me back up and lead the way again to this same precipice along a more strictly theological trail.

A fault in our knowing

It is no surprise that modern folks are fixated on the question of knowledge — how we know what we think we know and how we try to justify our thoughts to others. Much of what rises as our attitude toward the world is grounded in what we think we know. And many arguments that fester and erupt at dinner tables and in town halls across the country revolve around attitudes toward right and wrong, good and evil.

“It is no surprise that modern folks are fixated on the question of knowledge.”

This fixation on knowing has taken on a particular texture in American evangelicalism, much of which turns upon a fundamentalist way of holding the Bible as a secure, haveable source of knowledge. Historian Molly Worthen has named this complex of troubles as one of three key questions defining American evangelicalism over the last 100 years: “How do I keep truth one thing so that what I know by faith and what I know by Enlightenment reason remain the same?”

But few have reckoned adequately with the trouble that comes with living as though the fundamental problem of human life is resistance to believing the right things about the world. As Bonhoeffer tells the story of the first humans’ fall, and later the meaning of Jesus appearing in human form, this broken posture turns out to run deeper than we realize.

The creaturely limit to our knowing

Made in God’s image to live free and flourishing lives with and for others (starting with God), everything human beings could possibly have needed to know about anything — the world, ourselves, who God is — would emerge in the course of life. Learning about the world itself would unfold on the job, and other persons (including God) would make themselves known in the context of our relationships with them.

The basic act of sharing something about oneself with another person was and is the starting point for what theologians call “revelation.” Revelation is that form of interpersonal communication through which we disclose parts of our inner life (our character and motivation, our hopes and fears, and other unseen realities) to others. If we do not reveal these things, others cannot really know them. What God does not reveal, we cannot know about God.

When it comes to this most important variety of knowing in the world of God’s design, human beings have been blessed with a limit at our center. Much like a “governor” that keeps a go-kart running at lower speeds even when its motor can do more, this inner limit on our will to know can keep us running at the speed and efficiency of genuine, personal relationships.

Operating at our limit, we rise to the level of personal agency without either overreaching or overperforming when it comes to other persons. Examples of exceeding our limit include allowing our minds to put more on others than they have revealed of themselves or holding them to a flat or abstract notion of who they are. And we typically cross such lines within well before our actions toward others become coercive.

“Our minds, our very selves, are limited by design.”

So, while other people approach us from outside ourselves, they remind us of a limit within. We simply cannot know the most important things about other persons, who they are or what is on their minds, by sheer force of will. Our minds, our very selves, are limited by design. And, as we might guess, transgressing this limit puts us in a precarious position, generating (even if unconsciously) a wound within ourselves — a source of insecurity, confusion and pain.

The gift of others

God’s creation of the second human, Bonhoeffer tells us, truly embodies a gift to the first — a living co-bearer of the image of God who shares in this creaturely limit. The first two humans could look each other in the eye, love each other, and together mind and appreciate their limitedness. Such a life together, exploring God’s creation as creatures, would be qualitatively better than expecting the first human to do this alone (which God said was “not good”).

What do we do when we bump up against living boundaries to what we can know? On the one hand, in the absence of personal knowledge growing out of a relationship with the other person, we tend to project our own ideas onto them — starting with ideas that come together somewhat unconsciously based on our initial perceptions of who they are.

Scale this up and think about how many people we are aware of existing in the world. Think about what you know of different worldviews, different ways of life, different political systems, different religions. What does it mean to think of groups of persons in these terms? How broad are the strokes we paint with? And what kind of complexity do we miss? In this process, with individuals and groups, our will to know outstrips our ability.

On the other hand, how does this work with the persons we are closest to and regularly interact with? We may know some things about specific people, have categories in our minds for what they do and how they act and think, and we can live and move with a reliable sense of how they will live and move too — what we might call their “character.”

“From our place in the middle of a broken world, we must confess how challenging it can be to honor the limit within as we seek to know the invisible God.”

But there is still some mystery about who they are. Beloved others may defy our expectations, and although we struggle with this reality, they will grow and change over time. Nevertheless, it is the person we want to know, to be with, and not merely their stable ideas about the world as we understand them. (Among others, Spanish-speakers use different verbs for these two kinds of knowing: saber for the factual and conocer for personal familiarity.)

In either case, our response to the internal limit that rises in the presence of a living other applies to God just as much as other human beings. God is also personal, of course, but qualitatively different than a human person. From our place in the middle of a broken world, we must confess how challenging it can be to honor the limit within as we seek to know the invisible God.

A better way to be for God?

Reading the story of God’s creation of the world and the fall of humankind, Bonhoeffer explains, we tend to fixate on how the first human beings crossed a boundary that was outside of themselves. God set up a rule that marked out a physical boundary — do not eat the fruit from this tree — but they did it, which was plain and willful disobedience relative to that clear standard.

That is the story many of us have received. But the falling began before they ate the fruit, Bonhoeffer tells us, in a much more subtle way. The serpent put a “pious” question to them.

Adam and Eve were naive but loving persons, so it would not have been easy to convince them that they should do something that violated their friend and Creator’s plainly expressed will. The serpent’s question cunningly suggests that God might be happier with them if they just knew what good and evil were and chose to do the good things. There is a better way to be for God, if only you knew for yourself all that God wills. Already made in God’s image, you could be more like God.

“The first problem already was under way when the humans shifted the center of their reflections about who to be away from the relational context of life with their creator and into the self as the omnicompetent judge of what to do and why.”

To be clear, the importance of God’s word about the tree and its fruit was not that God named an objective, mechanistic relationship between the humans consuming some magical pomegranate and becoming more like God in their knowledge. The first problem already was under way when the humans shifted the center of their reflections about who to be away from the relational context of life with their creator and into the self as the omnicompetent judge of what to do and why.

And as they seized a new basis for knowledge of good and evil, the first humans took up a new attitude, raising labyrinthine walls around their fragile selves and deepening the fall. A fissure in their relationship with each other and with God was opening, making genuine self-revelation much more challenging. God had spoken directly to them, but the first humans’ trust was not enough to make the word stick when it seemed like there was more to be had — even if the “more” was masquerading as a more stable, more certain basis for understanding God’s will itself.

Hearts curved in on themselves

Could they not slow down to simply ask God? The focus on boundaries outside ourselves, Bonhoeffer tells us, blinds the human person to their inner limit as just one creature in the world.

(123rf.com)

The fundamental human problem, in Bonhoeffer’s view, is the cor curvum in se (Latin for the heart curved in on itself). Its symptoms include a broken connection with anything and anyone beyond the self, seeing and interpreting all things according to our individual reason and prior experience, and resisting those who challenge our concepts and categories — whether they do this intentionally or just by appearing before us in all their difference.

With hearts curved in on themselves, our interactions with other persons become less about nurturing relationships in good faith and more about how others might confirm our worldview and, if necessary, the ways we might coerce (or cancel) others according to it. Locating one’s center and most trusted source of stability within oneself is accompanied by patterns of thinking, feeling and acting that serve and protect this center. We prefer self-validation and inner peace to the more challenging prospect that genuine peace and security may depend on the authenticity of one’s life together with God and others.

And from this perspective on the human condition, we find ourselves back where we left off with Baldwin. Human beings try to secure a life for ourselves according to the illusion that (a) we are mostly defined by our attitude or worldview and (b) our inner peace can and must be maintained over against outside threats. “It has always seemed much easier to murder than to change.”

Bonhoeffer tells us in words that noticeably resemble these, the self-assured person who bumps into the living Jesus is confronted with two options: kill or be killed.

Taking a moment

When he taught his lectures on Christology, Bonhoeffer began with silence, explaining that we must maintain space for the living God to speak. Jesus approaches us through the normal, everyday reality that other persons transcend ourselves, he explains, so we must quiet our internal chatter and check our attitude if we hope to hear Jesus speak for himself.

That sort of experience is hard to replicate in written form. But, for now, I might leave off — tempted though I am to continue through to the end of the story — and let these final thoughts linger in the air. Why the living Jesus confronts us with these options, what it means for our world-viewing ways, and how Jesus might lead us into a different way of inhabiting this world will be the stuff of my final installment in this series.

This is the sixth article in a series introducing the hypothesis of the author’s new book, Worldview Theory, Whiteness and the Future of Evangelical Faith.

Jacob Alan Cook

Jacob Alan Cook is a postdoctoral fellow at Wake Forest University School of Divinity. He is the author of Worldview Theory, Whiteness and the Future of Evangelical Faith as well as chapters on Christian identity, peacemaking and ecological theology. He earned a Ph.D. from Fuller Theological Seminary.

Previous articles in this series:

Who needs the church when we have the biblical worldview?

What if your ‘Christian worldview’ is based upon some sinful ideas?

A short history of the roots of colonialism, racism and whiteness in ‘Christian worldview’

Putting the white in witness since the 1940s

Why your worldview might be both more and less than biblical