Note: This article includes a detailed description of burial preparation for children.

I embalmed a baby, for the first time, when I was 18 years old. Another baby I did not embalm — I could not embalm — lay on the other embalming table in the funeral home. She had been starved to death by her parents.

I embalmed a toddler, for the first time, when I was 19.

I have never talked to anyone about what I experienced in these past 56 years.

Harold Ivan Smith

In both cases, we (I was embalming with two others) quickly assessed the corpse. In those years before seat belts for adults and car seats for babies, in an automobile crash, the baby had been thrown through the windshield. We quickly concluded, “Closed casket.”

Then the funeral director spoke up.

“No, it will not be a closed casket.” When we started to protest, he snapped, “Boys, I tell you why this will not be a closed casket. There is a broken-hearted mama who wants to hold her baby one more time. And you are going to make that happen. You are going to give her back her baby. Now, if you don’t have any more questions, get to work!”

Hours later, a mother, whom I never met, held her baby again. That young mother never thanked me. In fact, the funeral director did not even say, “Well done, boys. Job well done.”

The toddler, a girl, had died in a medical center after receiving substandard care. There was even a question of how long she had been dead and why her body had been kept so long in a freezer. After being reminded that that medical center had the power to close down the funeral home and end our careers, we were sworn to secrecy. That toddler had suffered, and her parents and grandparents had suffered through her illness and dying. Now we suffered as we prepared her corpse. Her parents, her extended family, had expected a “miracle” at the medical center. And they got far, far less. We made that little girl look so much better than when her parents had last seen her. And then our work day over, we were among family and friends, and were asked polite questions, “So, how was your day?”

The heroes you never see

I think about those moments — moments that convinced me that I never could make a good embalmer — when I hear about the latest school shooting. Those last four words never should have been strung together in a phrase or sentence. Those words make up an increasingly common cliché: the latest school shooting.

After every “latest school shooting,” amazing individuals step forward. In Uvalde, Texas, Eulalio Diaz and a group of embalmers whose names I do not know stepped forward. None of them, at breakfast Tuesday morning, had said, “I sure hope we have some excitement in Uvalde today! Something out of the ordinary. Something that might put Uvalde on the map.”

Eulalia Diaz serves as justice of the peace in Uvalde County. Texas, unlike other states, does not have traditional elected county coroners. Rather, the Texas Constitution calls for justices of the peace to be elected for four-year terms. Duties of the justice of the peace include presiding over small-claims courts, performing civil weddings, conducting inquests and certificating deaths. (In large Texas counties which have medical examiners the justice of the peace transfers responsibilities for investigating and certifying death.)

‘It stays in your mind’

On Tuesday, Diaz was called upon — given his sworn oath — to walk into an elementary school, walk down the hall and into classrooms to begin identifying bodies. Or, to be blunt, what was left of those children’s bodies.

Later, when a reporter asked him about the experience, Justice Diaz replied, “It stays in your mind.” And it will.

“The ugly reality is that the tragedy in Uvalde will not stay in American minds.”

The ugly reality is that the tragedy in Uvalde will not stay in American minds — and in the minds of Texas or national politicians — any longer than previous outrages have. It does, however, “stay in the minds” of funeral directors and embalmers who have prepared the victims of carnage. It never has been “all in a day’s work” for those men and women.

In coming weeks, when some of those embalmers go to mass, walk into the grocery, sit at a Little League baseball game, no one will say, “Hey, aren’t you the guy who …?” Some are known only as “the guy at the funeral home.”

Soon all those policemen, politicians, FBI agents and especially the media personalities “reporting from Uvalde,” will pack up and move on. In fact, they will wait for the next outrage to erupt in an elementary school or a grocery store or a church somewhere in this gun-loving, gun-toting, gun-idolizing country.

I’d like to say a word for the embalmers

You may remember that delightful moment in the musical Oklahoma when the cast sings “The Farmer and the Cowman.” When a farmer in the chorus sings, “I’d like to say a word fer the farmer,” Aunt Eller snaps, “Then say it.”

This day “I’d like to say a word fer” the embalmers, for particular embalmers, men and women in Uvalde who prepared the bodies of 19 children and two teachers. I am not interested in extending “thoughts and prayers” to them. I am not interested in offering “a word of prayer” for them. I am interested in praying for them in the coming days and months, aware that although I do not know their names, God does. And God knows what Justice Diaz and those embalmers saw with their eyes and hearts.

We are quick in tragedies to pray for police and soldiers, doctors and nurses, and emergency technicians who responded. But how many times have you prayed for the funeral directors and embalmers? Oh, you may have said after a visitation or funeral, “You did a good job” and let it go at that.

What if we said, “I will deliberately and intentionally think about you, and I pray for you.”

“The embalmers rarely end up in anyone’s ‘thoughts and prayers.’”

The embalmers rarely end up in anyone’s “thoughts and prayers.”

It is one thing to embalm a 90-year-old. It is one thing to embalm a 55-year-old. It is another to embalm a 10-year-old.

An embalmer, of whatever age, knows she or he really should not be embalming an elementary school child killed by a deranged individual with an assault weapon. Let alone multiple children.

Admittedly, not every embalmer is good with working with families. Not every funeral director is good at embalming. In fact, many embalmers are more comfortable in what is called, “the back room.” I am utterly amazed by the skills of embalmers and by their commitment to “improving” final memories. Their willingness to spend, if necessary, incredible hours preparing the body.

I do not embalm but work as a funeral celebrant for a large funeral home in Southern California. I bury the dead. I console families and friends, colleagues and neighbors of the deceased. I work with families who do not — who definitely do not — want “a preacher” to preach at them. And they do not want a cookie cutter funeral service in which the minister merely inserts the name — if they even say the name — and the pronouns.

When I conduct open-casket funerals, I often compliment the embalmer or ask the director to pass on my compliments. Of course, funeral directors like to hear, “He looks so good” or “Just like she is asleep.”

I really wish I could ask the embalmer(s) to come in to the funeral service so we could formally recognize them.

The memories do not evaporate

By the time you read this, at least some of the funerals will have taken place in Uvalde. Well, then, you may ask, isn’t it a little late to pray for the embalmers of Uvalde. No, because the memories do not evaporate.

So, if you want to pray for grieving families in Buffalo or Atlanta or Aurora or El Paso or Thousand Oaks or Virginia Beach or Pittsburg or Parkland or Sutherland Springs or Las Vegas or Uvalde, please pray for the embalmers who must, in the words of Charles Wesley, “serve the present age, my calling to fulfill.” Some embalmers would tell you that they consider it a ministry.

Imagine an embalmer who is father or grandfather or uncle unzipping a body bag and seeing — not just with eyes but with the soul’s eyes — what a bullet or a rapid succession of bullets can do to a child’s body. I wish it were possible for those who strut, “Guns do not kill people! People kill people” to have to stand in an embalming room and watch an embalmer try to repair a gun’s damage!

“I wish it were possible for those who strut, ‘Guns do not kill people! People kill people’ to have to stand in an embalming room and watch an embalmer try to repair a gun’s damage!”

When an embalmer wakes up in the morning, they have no idea what the day will bring. Often, bodies easily and predictably prepared. Except, of course, when the deceased is someone they know, attend church with or a neighbor. No embalmer in Uvalde woke up last Tuesday and said, “I am possibly going to have to do the impossible after the unimaginable.” Just as no embalmer got up that Saturday morning in Buffalo anticipating the carnage in a grocery story.

One scene in The Godfather has stuck with me over the years. In fact, I often use a film clip or photo of the scene when I do continuing education seminars. Sonny Corleone, oldest son of mobster Vito Corleone, has been “taken out” in a “mob style” ambush at a tollbooth on the Jones Beach Causeway. To say the least, the assailants used “excessive force.”

In the clip, we watch the heartbroken Don Corleone ride the elevator down to the basement of the funeral home. He slowly walks toward the embalming table where his beloved firstborn son lies. Corleone lifts the blanket and gasps at what remains of his son’s face.

Then he groans from somewhere deep within — a place we assume a mob boss possesses. “Look how they massacred my son.” Then he speaks to Amerigo Bonasera, the funeral director.

“I want you to use all your powers and all your skills. I don’t want his mother to see him like this.” He did not have to conclude, “Do I make myself clear?”

Admittedly, most families in Uvalde will not issue those words. But, like Don Corleone, they hope a funeral director and embalmer(s) will use all their powers and all their skills. So that, some way, their child will not look so much like when they last laid eyes on them. But more how their child looked when they dropped them off for school.

The embalmer will make certain the child does not look like they looked when he or she opened the body bag.

Pray for Eulalio Diaz

A tired old cliché insists that “a picture is worth a thousand words.” That cliché drifted across my mind when I noticed a small photo at the bottom of page 6D of the May 26 USA Today. That’s where I was introduced to Eulalio Diaz, the justice of the peace who had to identify the bodies of the slain children and teachers.

As a lifelong Uvalde resident, he knew many of the parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles now thrust into grief’s headlock. Never had he imagined that someday he would have to identify the body of his high school classmate, Irma Garcia, a teacher, after a school shooting.

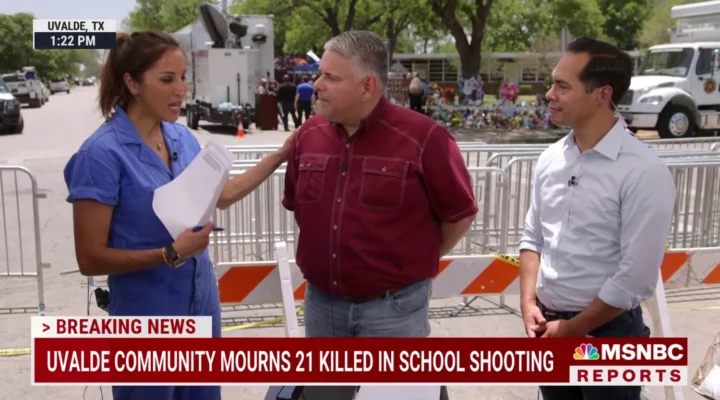

The photo captured the compassion of Constable David Valdez, who had embraced Justice Diaz after listening to him recount the narrative of identifying those children. Valdez embraced and consoled his friend and colleague.

When you pray, would you particularly pray for Eulalia Diaz?

And would you pray for unnamed embalmers whose faces did not appear in USA Today, those who embalmed 19 children and two teachers who, in a just world, would now be experiencing their first days of summer vacation.

If after reading my words you conclude, “I wish I had read this article earlier because those children are dead and buried in Uvalde,” remember to keep my words handy. Because without doubt, there will be another mass shooting. And embalmers in another town will need your prayers sooner than you think.

Harold Ivan Smith is thanatologist and independent scholar. For 18 years he served on the teaching faculty of Saint Luke’s Hospital in Kansas City, Mo. He earned graduate degrees from Scarritt College, Vanderbilt University, and a doctor of ministry degree from Asbury Theological Seminary. His writings include A Decembered Grief, On Grieving the Death of a Father; Grieving the Death of a Mother; When You Don’t Know What to Say; When a Child You Know Is Grieving, When Your People Are Grieving: Leading in Times of Loss.

Related articles:

On this date 85 years ago, the worst school tragedy in American history occurred | Analysis by Harold Ivan Smith

After Uvalde, let us dream of impossible things | Opinion by Andrew Manis

On another classroom full of murdered children | Opinion by David Gushee