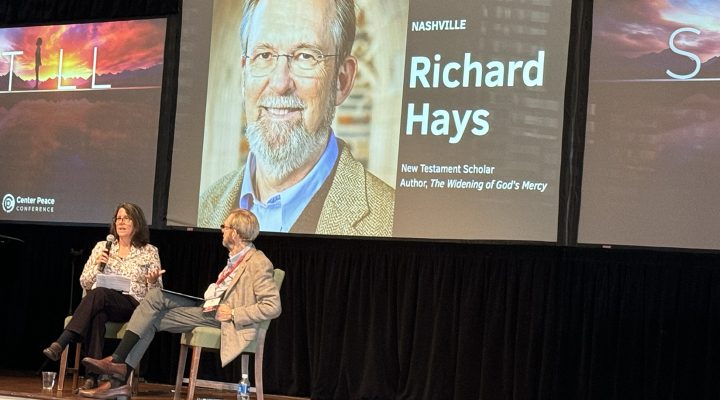

When you come across something in your history that is wrong, “the thing to do is to confess and seek forgiveness,” Richard Hays told a large gathering of LGBTQ Christians and allies Oct. 25.

Hays, a New Testament scholar who is retired dean of Duke Divinity School, recently published a much-anticipated book in which he recanted his previous writings that argued against affirmation of same-sex relationships. His earlier work, published 30 years ago, had become the gold standard for evangelicals who are nonaffirming.

Richard Hays

That book — The Moral Vision of the New Testament — was named by Christianity Today as one of the 100 most important religious books of the 20th century.

However, after it was published, Hays began to realize the one chapter inside it about homosexuality was wrong, he told about 500 participants in the biennial CenterPeace Conference held at Wilshire Baptist Church in Dallas. The conference was sponsored by CenterPeace, an independent nonprofit with roots in the Churches of Christ.

That 25-page chapter became “the one thing (people) know about me,” he said. “I didn’t want that to be my legacy because I had come to think it was wrong. And when you come across something that is wrong, the thing to do is to confess and seek forgiveness.”

The response to the new book, The Widening of God’s Mercy, has indeed been mixed, with Hays and his co-author son being assailed by conservatives as sell-outs and being doubted by progressives who believe the 30-year-old book has done irreparable harm to LGBTQ Christians.

Nevertheless, in the middle of Hays’ presentation last Friday afternoon, an unidentified woman shouted out from the back of the room: “In the name of Jesus Christ, you are forgiven!”

A palpable silence fell across the room, and Hays quietly acknowledged the woman by bowing and holding his hands in prayer.

He explained to the gathering that he hopes his change of mind will alter his inevitable obituary. Before writing the new book, he feared his obituary would begin: “New Testament scholar Richard Hays, who wrote against the acceptance of gay and lesbian people, has died.”

Instead, he now hopes his obituary might begin: “New Testament scholar Richard Hays, who changed his mind on the acceptance of gay and lesbian people, has died.”

That wish for a different obituary is not for ego purposes, he said, but because he genuinely has changed his mind.

New Testament scholar and author Karen Keen interviewed Hays for the hour-long seminar.

At the end of the session, she asked him: “We encounter a lot of LGBTQ people who are wondering whether it’s possible to hold onto to their faith, whether it’s worth it. … What word of spiritual exhortation would you give to LGBTQ people?”

After pausing for a long moment of reflection, Hays answered: “I would say to them, to all of you, I would say, No. 1, know that your identity is grounded in the God who loves you despite the failings of the church to communicate that love. No. 2, I would say try to find a church community in which you can be received joyfully and fully as a member of the body of Christ. And such communities do exist. … You need to seek that kind of community because the support of the community is very critical to maintaining one’s sense of identity.

“Know that your identity is grounded in the God who loves you despite the failings of the church to communicate that love.”

“But the ultimate word is that we are in the merciful hands of a God who loves us and seeks to draw us to himself and to bind us together in the one body of Christ … as a forgiven and reconciled people. Find those friends and communities that give you that kind of support and communities that proclaim and live that truth about God as welcoming all to the table.”

Hays received a prolonged standing ovation from the seminar participants in what is likely to be one of his last public appearances due to serious health challenges.

Where he came from

Hays is the son of a female United Methodist preacher who had a two-point charge in rural Southern Oklahoma. Eventually, the family moved to Oklahoma City, from where Hays departed as a young man to earn a bachelor’s degree and master’s degree from Yale University. He later earned a Ph.D. in New Testament from Emory University.

He returned to Yale Divinity as a professor for 10 years before being hired at Duke Divinity, where he spent the rest of his career.

Hays has been called by other scholars one of the premier New Testament scholars of his generation.

Hays has been called by other scholars one of the premier New Testament scholars of his generation.

Although it doesn’t show up on his vita, Hays began his graduate theological studies just a few miles from where the conference was held in North Dallas, at Perkins Seminary of Southern Methodist University. Hays was then and remains today a United Methodist.

“I came right out of Yale University in 1970,” he recalled. “The world is melting down with the Vietnam War protests against it. In New Haven, Conn., where I was that spring, the university actually shut down out of concern for potential violence. … This is the world I came out of when I went to seminary and then I landed in Dallas 1970 and I felt like I was the most politically liberal and at the same time was theologically conservative of anyone in my class.”

“It was a strange feeling, and I pretty quickly decided this wasn’t for me and I bailed out and I went and lived — my wife and I lived — in a Christian community in Massachusetts — an extended possession-sharing community, very formative for me.”

Eventually he decided he really was called to ministry and needed theological education. He returned to Yale for that but approached theology with the mind of an English major, which he had been as an undergraduate.

“I was taking classes on the Bible in New Testament and I came in out of those classes thinking, ‘What in the heck are they doing with these texts?’ Because the whole approach was to try to dig beneath the surface of the text and reconstruct sources or the history behind the text. There was never, in my experience at the time, an attention to the final form of the text, the shape of the text and how it was working as a narrative. It was always concerned about precursors to the text.

“It would be as if you were taking a class on Shakespeare and you were reading Hamlet or trying to just reconstruct Shakespeare’s sources without ever engaging the literary effect of the finished product. So I quickly began to see if there’s something wrong with the church and the theology that I would like to address simply, I want to teach, I want to learn and I want to teach people how to read the Bible better.”

“Scripture is the wellspring of life. … But the way we read it is not just to pick out proof texts.”

And that remains a basic challenge in the study and teaching of theology today, he quipped. “There are some people with this recent book who maybe haven’t read much of my other work who might say, ‘Oh, they’re denigrating the authority of Scripture because the Bible clearly says … .”

The truth is “by no means (did) Chris and I object to the authority of Scripture. It’s a difference about how we read Scripture as authoritative for our lives. That’s what we try to work out in the book. But for me, Scripture is the wellspring of life. … But the way we read it is not just to pick out proof texts, sound bites out of the story, it’s to see the whole shape of the narrative from beginning to end.”

Surprising mercy

In the new book, Hays and his son portray the character of God as merciful and “continuing to surprise us with his mercy,” he said. “One of the persistent themes of the Bible as a whole is actually that it is often the people who think they’re being the most zealous servants of God and most strictly obedient to God actually turn out to be caught by surprise by the way God shows up and displays mercy in unexpected ways.”

A secondary theme is about how to read the Bible. “Well, read big chunks of it, read the shape of the story,” he advised. “Don’t just pick out verses here and there. We all know that when you start the business of picking out verses, you can open the page, put your finger down, then find the passage in Deuteronomy that says, ‘If you have a disobedient son, take him before the city authorities and have him stoned to death.’”

Christians and Jews today don’t read that as a literal command binding for all time, he said. “If I did that first, I never would’ve had a son to write this book.”

It is in the narrative of Scripture that Christians will find “a clearer picture of the identity of God,” Hays advised.

Likewise, his new book’s emphasis on God’s mercy has been wrongly portrayed by critics who have not read the book or who have misunderstood it, he said. “It’s really striking when you start tracing that language through Scripture and you see God in Exodus revealing himself to Moses and saying, ‘I’m a God merciful and gracious, longsuffering, showing compassion to many’ and so on. And Christians, if we have our theology straight, all understand that we’re all the recipients of God’s mercy. When we read the story, we find ourselves in the son who returns and receives his father’s welcome. Not in the self-righteous older brother who says, ‘You never do anything for me.’”

Changing God’s mind

Keen asked the scholar to explain a teaching in the new book that God can and does change God’s mind.

A tension that “has really knocked some people back is the claim that God changes,” Hays said. “And that may be difficult to square with our image of God if we believe in what the classic doctrine of God is. The problem is that the stories that are told in Scripture, God who is unchanging, there are plenty of stories that do show God changing his mind.”

It is true that God is unchangeable, but “he’s unchangeable in that he has revealed himself as a god who changes.”

Change is “built into the story,” he continued. “And oddly, most of the people I’ve seen who actually raised that objection in print are the people who would consider themselves biblical inerrantists. They are people who say the Bible is without error, it’s all pure truth. But then they come to the parts where God changes his mind and they say, ‘Well, but that doesn’t mean really what it says.’ And I sort of scratch my head because they’re more committed to a doctrine that is much more rooted in Greek philosophy than it is in Scripture.”

The Aristotelian concept of God as the “unmoved mover” does not square with Scripture, he said. Scripture shows “a dynamic personal God who engages passionately with people, who is grieved when we go astray, who is like a father. That’s the God of Scripture. So I just keep coming back to that, that God is who God shows himself to be.”

It is true that God is unchangeable, but “he’s unchangeable in that he has revealed himself as a god who changes.”

Hays said he received a question from British New Testament scholar N.T. Wright — who had not yet read the book — who said, “If God could change his mind about human sexuality, how do you know God isn’t going to change his mind and turn around and refute your chapter on nonviolence?”

Hays admitted that’s a fair question “and the only answer I’ve got to it is to keep saying, ‘Let’s go back to the text and see how God’s mysterious ways do unfold in ways that continue to demonstrate an expansive compassion for human beings. For all of us who are created in God’s image, God ultimately seeks to redeem all. And that’s the way that works itself out in history. … God is the God who continues to reach out to us.”

Related articles:

Analysis: What to expect from The Widening of God’s Mercy | Analysis by Karen Keen

The healing ‘heresy’ of Richard Hays | Opinion by Brandan Robertson

An oft-quoted biblical scholar changes his mind on LGBTQ inclusion in the church

A new book on the Bible and LGBTQ folks by a straight, white man is not what we need | Opinion by Susan Shaw