Church/state mandates began early in the American colonies.

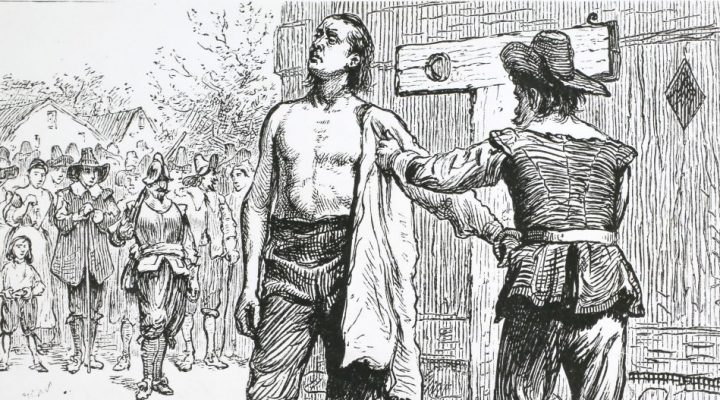

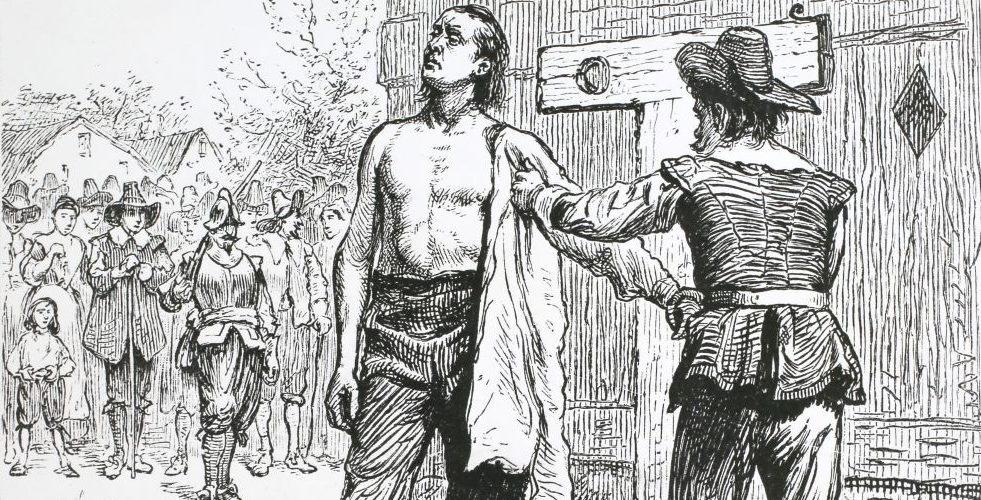

On July 19, 1651, three Baptists — John Clarke, Obadiah Holmes and John Crandall — traveled from Newport, R.I., to Lynn, Mass., and the home of William Witter, who requested their visit to assist friends seeking baptism by immersion. On Sunday, July 20, the three conducted a service attended by several of Witten’s friends.

Knowledge of the gathering got around, and two local constables arrived to arrest the three, but instead compelled them to attend an afternoon service at the Congregational/Puritan church in Lynn. Entering the church, Clarke and Holmes did not remove their hats, which were pulled off by the constable. During worship, Clarke stood and denounced the congregation for their practice of infant baptism.

Released by authorities, the three returned to Witter’s home, where the next day they held another service, shared the Lord’s Supper and baptized several other people.

On July 22, the men were arrested and jailed in Boston. The next week, they were tried and found guilty of violating the Massachusetts colony’s church/state mandates, including conducting an unlicensed religious service, wearing hats during worship, the inappropriate administration of Communion, rebaptizing people previously baptized as infants and denying the biblical validity of infant baptism.

Fined by the court, they were ordered to pay or “be well whipt.” The three refused, but friends of Clarke paid his fine, while Crandall put up his own bail money. Released from custody, the two returned to Rhode Island.

“You have struck me as with roses,” 17th century Baptist pastor Obadiah Holmes responded after receiving 30 lashes with a whip for dissenting Massachusetts church/state mandates.

But Holmes remained in prison until September, when the court ordered him to receive 30 lashes, administered with a three-corded whip. It was a bloody affair, to which Holmes responded: “You have struck me as with roses,” so greatly did he sense the Spirit’s presence and the significance of his public witness against the Massachusetts religious establishment.

That story is recounted in Soul Liberty: The Baptists’ Struggle in New England, 1630-1833, published in 1990 by longtime Brown University history professor William G. McLoughlin.

McLoughlin challenged certain “misunderstandings” about the development of religious liberty in the American colonies. He wrote such freedom “evolved neither from” the Enlightenment-inspired sentiments of Thomas Jefferson and other American “founders,” the “soul liberty” concerns of radical separationists like Roger Williams and John Clarke, or the early dissenting witness of the 16th century Anabaptists.

He also insisted the Constitution’s First Amendment did not “conclude the struggle,” adding, “Most historians today believe it can never be concluded.”

McLoughlin posited: “The development of the unique American tradition of separation of church and state was far more ambiguous and pragmatic. … The tensions between the state authority and private religious freedom have been, on the whole, central to the expansion of liberty in America from its first settlements, and they remain a vital element in the dynamics in American culture today.”

For McLoughlin, the religious freedom that took shape in the South against the Anglican establishment, and in the North with the Puritan establishment, “had less to do with ideology than with the very practical exigencies of finding spiritual self-expression within the limited bounds available to dissenters within these establishments.”

As these dissenters pushed back against church-related mandates set by colonial governments, the process toward religious liberty gained ground.

Yet McLoughlin cautions: “No sooner did Christian dissenters achieve their goal of voluntarism in the early 19th century than they formed an alliance against those outside the prevailing Evangelical Protestant consensus.” He contends this emphasis led to a second de facto religious establishment, promoting yet another “tyranny of the majority” whereby “non-Protestants were instructed to be satisfied with toleration and second-class citizenship or to go back where they came from.”

Soul Liberty cites an 1867 comment from a New York Presbyterian minister who asserted, “This is a Christian republic, our Christianity being of the Protestant type.” He noted that non-Christians and non-Protestants “dwell among us; but they did not build this house,” adding those dissatisfied with that reality “will do well to try some other country.”

How often have we heard parallel ideas and statements like that in this presidential election year?

Whatever else Christian nationalism means, it is surely yet another effort in American history to re-establish a particular type of Christianity …

Recent legal mandates requiring posting the Ten Commandments in Louisiana public school classrooms and the Oklahoma mandate adding Bible classes to the public-school curriculum illustrate that, whatever else Christian nationalism means, it is surely yet another effort in American history to re-establish a particular type of Christianity, largely but not exclusively Protestant, as a governmentally privileged, hegemonic national religion.

In a June 27 memo to “Oklahoma Superintendents,” state Superintendent of Public Instruction Ryan Walters, wrote: “This is not merely an educational directive but a crucial step in ensuring that our students grasp the core values and historical context of our country. Adherence to this mandate is compulsory. … Immediate and strict compliance is expected.”

Newsweek recently reported that, speaking on “Fox & Friends,” Walters responded to school district dissent against the state mandate that all teachers must prepare to teach the required Bible courses by saying: “I’m going to tell these woke administrators, if they’re going to break the law and not teach it, they can go to California. Here in Oklahoma schools, we’re going to make sure that history is taught.”

Guidelines were issued to ensure all teachers understand what is expected of them, Walters said.

As this program begins in the fall, questions abound. These surely include:

- How will conservative parents respond when the Bible teacher(s) reference theories of biblical inspiration outside the concept of inerrancy?

- Will parents want to know the religious identity or lack thereof from those teaching Bible to their children?

- How will families from non-Christian faiths, or families who claim to be religiously unaffiliated, respond to the biblical studies mandate? Might exclusions be permitted? Will excluded students be subject to targeting by other students?

- Will discussions of the creation story, complete with the expulsion of Eve and Adam from the garden, or references to eternal punishment create student “discomfort” in ways that have led some schools to censor studies related to slavery and racism?

- What is the purpose of requiring all teachers to prepare to teach the Bible? Is it an effort to get teachers involved in biblical studies and encounter the spiritual benefits thereof?

- Is the movement to require biblical studies in public schools related in any way to the decline of Sunday school attendance in many churches across the theological and denominational spectrum? Are we asking the government to provide biblical education now that churches seem no longer able to do so?

It appears such church/state mandates will continue to be expanded across the United States.

Reflecting on that increasing reality, I find myself returning to a statement by the late, great Baptist historian Edwin Scott Gaustad who wrote, “Consent makes democracy possible; dissent makes democracy meaningful.”

And I return again to the thought and actions of those Baptist forebears who carried on the struggle for religious freedom long before our generation entered the world. Virginia Baptist preacher John Leland (1754-1841) said it like this: “The liberty I contend for is more than toleration. The very idea of toleration is despicable; it supposes that some have a pre-eminence above the rest … whereas, all should be equally free, for Jews, Turks, Pagans and Christians.”

Leland added: “Whether … the Christian religion be true or false, it is not an article of legislation. In this case, Bible Christians, and deists, have an equal plea against self-named Christians, who … tyrannize over the consciences of others, under the specious garb of religion and good order.”

I’ll continue to believe that, regardless of the outcome of this November’s election. Yes, by God, I will. I’m hoping I won’t “be well whipt.”

Bill Leonard is founding dean and the James and Marilyn Dunn professor of Baptist studies and church history emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, N.C. He is the author or editor of 25 books. A native Texan, he lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Candyce, and their daughter, Stephanie.

Related articles:

Oklahoma schools chief mandates Bibles in every public school classroom

Ryan Walters descends from the Capitol with new commandments for Oklahoma teachers

Oklahoma school districts pushing back on Bible mandate

Oklahoma superintendent of schools says Tulsa Race Massacre wasn’t due to color of anyone’s skin

Baptists oppose Louisiana Ten Commandments bill

Gov. Landry gets his wish: Louisiana Ten Commandments law to be challenged in court