Mark Galli is best known in the United States as the former editor in chief of Christianity Today who took on Donald Trump as being morally unfit for the presidency. Late last week, he lit another fire, this time not from the pages of the nation’s flagship magazine for evangelical Christians but from his own online blog.

The subject is still somewhat Trump related, but this time Trump is the symptom, not the problem itself. What lit up Twitter over the weekend was Galli’s description of the two divergent paths he believes evangelicalism is choosing between right now.

One path is the kind of “elite evangelicalism” historically represented by Christianity Today with leaders desperate for approval from secular powerbrokers, and the other path might be a strain of neo-Calvinism that doesn’t much care what anyone thinks about its beliefs.

Responding to two young writers

The framework for his argument did not originate with Galli. He was responding to another article published on the website of The American Conservative. That article was not written by well-known evangelical leaders but by two young conservatives, one still a senior in college at a Baptist-related school.

Jackson Waters

That Oct. 1 piece, “Church, State and the Future of Evangelicalism,” was written by Jackson Waters, a senior at Union University in Tennessee, and Emma Posey, coalitions manager for American Moment, a politically and theologically conservative advocacy group.

Waters, according to his LinkedIn profile, is a history major pursuing ordination in the Anglican Church of North America, the conservative group of churches that broke away from the Episcopal Church in the United States. Posey is a recent graduate of Lee University, a conservative Christian school in Tennessee. Galli, who previously identified with the evangelical Protestant tradition, last year was confirmed into the Roman Catholic Church.

Emma Posey

Waters and Posey set up their article by offering a dualistic path forward for evangelicalism, which they say is “in a bind.” That bind is illustrated by support for Trump on the one hand and, on the other hand, those who sense that supporting Trump is bad for the evangelical brand.

“Overwhelmingly, self-described evangelicals supported Trump; yet almost as commonly heard as the 81% who made up that statistic were the 19% of evangelicals, many of disproportionately higher economic status, who opposed him (some of whom have now disavowed the title ‘evangelical’ altogether). Over the last year, the division between evangelicals and their leadership has only grown, raising the question of who is driving the movement,” they wrote.

Two events in Nashville

They then contrast two events that recently happened in Nashville at the same time. One was the launch of Christianity Today’s Public Theology Project with a live podcast recording of the Russell Moore Show, with Beth Moore as guest. The other was a three-day conference on “The Politics of Sex” with Idaho pastor Doug Wilson and the Fight Laugh Feast Network, a group of Calvinists that features the teaching of Tom Ascol, Voddie Baucham, Josh Buice and Jared Longshore, among others. Ascol has been a prominent voice within the Southern Baptist Convention calling for a new reformation to weed out liberalism. He also has been a staunch critic of Russell Moore, who this summer stepped down from leading the SBC’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission. Both Wilson and Baucham are highly controversial figures, both inside and outside evangelicalism, because of their writing that critics say empowers racism.

Russell Moore and Beth Moore recording the podcast.

Both Russell Moore and Beth Moore (who are not related) have denounced Trump and expressed dismay that so many evangelical Christians have empowered him despite his lack of morality and his blatant racism.

Waters and Posey described the podcast recording thus: “Together, the two Moores exchanged feelings of surprise at their departure, disgust at the SBC backlash, and encouragement to evangelical observers to stay in their churches, offering helpful pop psychological tips on how to navigate church conflict.”

And of Wilson and company: “Wilson, a pastor, has been simultaneously one of the most controversial and most productive Christian leaders of the last 40 years, due to his contributions to the classical Christian education movement, outspoken paleo-libertarianism and cavalier attitude, and countercultural community in Moscow, Idaho. Also headlining the conference was Voddie Baucham, a fire-and-brimstone Black American pastor and missionary to Zambia who has unabashedly taken to task mainstream evangelical leaders for their equivocation about and sympathy for critical race theory.”

These two events, the couple wrote, represent distinct paths forward for American evangelicalism. “While not all evangelicals fall into these extremes, these two groups provide the bookends of respectable evangelical opinion, punch above their weight in the church, and have an outsized influence on conservative Christians in America, and so their gatherings, and what they shared and where they differed, merit further consideration.”

“While not all evangelicals fall into these extremes, these two groups provide the bookends of respectable evangelical opinion.”

Further, watching the two groups, they wrote, “the form and substance could not have been more different. Russell Moore and Christianity Today epitomize the best and most articulate evangelical rejection of both Donald Trump and the politicking of Southern Baptist leaders. Doug Wilson and the Fight Laugh Feast conference repudiate neutrality in the public square and champion the church as an explicitly political entity, citing Scottish Covenanters and the Reformed resistance theology.”

Cultural accommodation and wokeism?

Waters and Posey believe the direction espoused by Moore and Moore “is not simply traditional evangelicalism, but a form of cultural accommodation dressed as convictional religion. The result is a religious respectability that promotes national unity, liberalism, and wokeism under the rhetorical guise of love for neighbor. While Moore and his guest try to straddle the fence, there is little doubt that their biggest support is now coming from those significantly to their left politically.”

Doug Wilson

Wilson and the Fight Laugh Feast, on the other hand, offer “a refreshingly sophisticated bulwark: a Puritan theology paired with an expectation of resistance. Whether such defiant Calvinist teaching can sufficiently permeate evangelicalism remains an open question, but where it takes root, it will not quickly recede. Wilson and Sumpter’s disinterest in social status makes them invulnerable to social pressure, a lesson that rank-and-file evangelicals have internalized but evangelical elites such as Russell Moore and the editors of Christianity Today continue to miss.”

Evangelical self-esteem

The latter comment was a reference to a 1994 book by Notre Dame historian Mark Noll, The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, who wrote that “the scandal of the evangelical mind is that there is not much of an evangelical mind.”

For his part, Galli agreed that Noll’s description was and remains a defining motivator for mainstream evangelicalism.

“These evangelicals want to appear respectable to the elite of American culture,” he wrote in reply. “This has been a temptation since the emergence of contemporary evangelicalism in the late 1940s, the founding of Christianity Today being one example. Letters between first editor Carl Henry and founder Billy Graham suggest the desire to be in essence an acceptable fundamentalism: Grounded in conservative theology while gaining the respect of secular academics and other cultural leaders.”

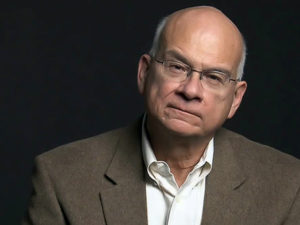

Mark Galli

This insecurity and thirst to be accepted led early evangelical leaders, including many professors at Fuller Theological Seminary, to earn doctorates not from evangelical schools but from Harvard or Oxford or other elite schools, Galli explained.

“One also saw this in the strategy of Young Life in the 1950s and 1960s. The key was to find or convert one of the “cool kids” (athletes, cheerleaders, class president, etc.) on the high school campus and encourage them to attend the weekly meetings. Get the influencers, it was said, and you’ll increase the number of kids who attend and eventually give their lives to Christ.”

In sum, he wrote: “Elite evangelicals are not just savvy evangelists but also a people striving for acceptance.”

Experience at Christianity Today

That is the world Galli came from, where he worked for several decades as managing editor and then editor in chief of Christianity Today. In his response, he tells stories about his experiences with evangelicals seeking secular validation.

He explained: “For the longest time, a thrill went through the office when Christianity Today or evangelicalism in general was mentioned in a positive vein by The New York Times or The Atlantic or other such leading, mainstream publications. The feeling in the air was, ‘We made it. We’re respected.’ This irritated me, because I naturally believed that CT’s outlook was superior (since it was grounded in the truth of the gospel and not secularism), so I often commented that we had things backward: The New York Times ought to be thrilled when it gets a positive mention in Christianity Today.”

The bigger problem, as Galli sees it, is that the evangelical elite only get published on topics that don’t challenge secularism and are not read by the average evangelical in the pew anyway.

“Their writing doesn’t reach the masses of evangelicals who take a contrary view and don’t give a damn what The New York Times says.”

“Their writing doesn’t reach the masses of evangelicals who take a contrary view and don’t give a damn what The New York Times says. If these writers are really interested in getting those evangelicals to change their minds, the last place they should be is in the mainstream press. Better to try to get such a column published in the most popular Pentecostal outlet, Charisma. Ah, but that would do nothing to enhance the prestige of evangelicals among the culture’s elite.”

Galli adds: “When you seek to win the favor of the powerful, you will likely be used by them to enhance their own status. And along the way, many of your convictions will be sidelined. We’ve seen this happen on the religious right in the political nightmare of the last few years. But it happens on the left just as often.”

He believes this quest for acceptance leads to a form of accommodation by evangelicals.

“Anyone who has studied the decline of mainline Christianity knows that such are the first signs of ethical retreat on an issue. It starts with ‘no easy answers’ and moves to ‘here’s an exception’ to eventual full acceptance. But history is not a one-way street, and this is hardly an iron law. I’m not saying that CT or these other evangelical orgs are racing toward liberalism. I’m only saying that the temptation to be accepted by the larger culture is immense, for reasons both evangelistic and psychological.”

But what or who is the alternative?

While Posey and Waters get this part right, they miss the mark on naming the alternative future of evangelicalism, Galli asserts.

“The authors are right about CT being one of those. But Doug Wilson and his following are a tiny and inconsequential part of the evangelical movement. Recent accusations of sex and wife abuse in Wilson’s Moscow, Idaho, community will only sideline that movement even more.”

“It is a major force that someday could supplant Christianity Today as the major intellectual voice of conservative Christianity.”

Instead, an alternative “will have to be a group with some intellectual and psychological backbone, like Doug Wilson’s, but not so idiosyncratic. I’d offer The Gospel Coalition. It is a major force that someday could supplant Christianity Today as the major intellectual voice of conservative Christianity.”

“The Gospel Coalition has the finances and, more importantly, a substantive theological foundation to better resist the enticements of the cultural elite,” Galli wrote. “Naturally, as a Catholic, I disagree with some of Calvinism’s distinctives; still one has to admire its architecture and depth and Calvinists’ stubborn faithfulness to tenets that offend the surrounding culture.”

What is The Gospel Coalition?

The Gospel Coalition describes itself as “a fellowship of evangelical churches in the Reformed tradition deeply committed to renewing our faith in the gospel of Christ and to reforming our ministry practices to conform fully to the Scriptures.”

Tim Keller

Its best-known board member is Tim Keller, the New York City Presbyterian pastor and author who has become the face of the kind of Reformed evangelicalism that puts a softer brush on the often-harsh doctrines of Calvinism.

Two of the six SBC seminary presidents — Al Mohler and Danny Akin — serve on the group’s larger council, as does Russell Moore. Other council members include John Piper, a popular author and pastor who recently has come under intense critique for authoritarian leadership; David Platt, former president of the SBC’s International Mission Board who now serves as pastor of a Virginia church; and John Onwuchekwa, an Atlanta pastor and church starter who made headlines when he withdrew his church from the SBC because of its close relationship with the Republican Party as defined by Trump.

While The Gospel Coalition espouses a complementarian view of gender that only allows for male leadership, the group’s leadership is more racially diverse than most other evangelical bodies. About one-fourth of the members of its leadership council are persons of color.

The future of evangelicalism

As for the future of evangelicalism, The Gospel Coalition’s website includes multiple articles addressing the question from various viewpoints. Some agree that the word itself is no longer useful, while others propose ways to reclaim or redefine the evangelical label.

And some of them agree with Galli, who once was a leading light among the evangelical elite, when he says the “evangelical religion has become theologically pluralistic and incoherent; as such, it is too subject to the changing winds of secularism to stand erect in the hurricane of our times.”

From Galli’s experience, the challenge for Christianity Today and its brand of evangelicalism is that “there is no there there.”

Related articles:

Six ways ‘American Gospel’ is small-minded and abusive | Analysis by Rick Pidcock

Politics may drive evangelicalism to extinction, Galli says in BNG webinar

Has conservative evangelicalism reached a dangerous moment of its own making? | Opinion by Susan Shaw

‘Hour of decision’? Evangelicalism in a post-church, post-Trump era | Opinion by Bill Leonard

Who is Jesus Christ for us today? | Opinion by David Gushee