There is a popular trend among some evangelicals to criticize both sides of political and religious debates equally while proposing a third way that appears to be above the fray.

They might say, “While the right says this and the left says that, I say this!”

Or the more clever might propose, “Some follow a donkey, some follow an elephant. But I follow the Lamb!”

Third-way evangelicals operate along a spectrum of religious and political frameworks that may appear to them to be transcendent but in reality may not be as centrist as they think.

For example, the Baptist church I grew up in, as well as the university I attended, claimed to be part of a more moderate third way because we were not KJV only, even though we only used the KJV.

The church I helped start claimed to be part of a third way because we shed the Baptist label of our conservative financial supporters and were not part of the seeker-sensitive church movement. That didn’t make us any less conservative.

The Anglican church I eventually attended claimed to be part of a third way because we allowed women priests, even though we still were non-affirming of LGBTQ people.

Conservative vs. progressive centrists

Adam Joyce

In an excellent article for ABC Religion and Ethics, Adam Joyce provides an introduction to these Christian centrists. He distinguishes between conservative centrists, whom he identifies as “Tim Keller, Richard Mouw, Tish Harrison Warren, Skye Jethani, Jake Meador, the evangelical faith and work movement, organizations like the Trinity Forum, and magazines like Christianity Today,” and progressive centrists, whom he identifies as “Brian Zahnd, Eugene Cho, Greg Boyd, Brian McLaren, the Jesus Collective, and the Wild Goose Festival.”

Of course, even within those two groups are varieties of perspectives on the nature of God, theories of the atonement, views of universal salvation or perspectives on hell, what women are allowed to do, standards for human sexuality and political convictions.

Regarding what these conservative and progressive centrists have in common, Joyce says, “Even with their theological differences, conservative and progressive centrists end with a performative similarity: faithful politics concentrates on the ecclesial infrastructure of discipleship, personal sanctification, and advocating for church unity and mobilization. In politics as in life, Christians are foundationally called to unity in faithfulness, not victory or success.”

“Are both sides equally to blame for our nation’s lack of coming together to solve our common problems?”

Another characteristic they share is a tendency to blame both sides of the religious and political divides equally, proclaiming, “There are fundamentalists on both sides!”

But are both sides equally to blame for our nation’s lack of coming together to solve our common problems?

Cooperating to solve problems vs. overcoming your opponents

In March 2022, Samuel Perry — an associate professor of sociology at the University of Oklahoma — participated in a study fielded by YouGov, a UK-based market research and data analytics firm founded in 2000.

Their poll asked American respondents if it was “more important to overcome differences to solve problems or overcome opponents.” From a representative national sample of about 2,800, Perry observed, “Who prioritizes political cooperation to solve problems? Everyone except white evangelicals.”

Perry said the data are “proprietary at the moment” but eventually will be made public at the Association of Religion Data Archives.

“Those who lean ‘strong Republican’ believe it’s more important to overcome your opponent than to try to overcome your differences to address common problems.”

However, he was willing to reveal that those who lean “strong Republican” believe it’s more important to overcome your opponent than to try to overcome your differences to address common problems more than those who lean “strong Democrat” — by 63.5% to 28.3%.

Additionally, 72.1% of those who identify as “very liberal” believe in overcoming differences, while an almost polar opposite 64% of those who identify as “very conservative” believe in overcoming opponents.

Samuel Perry

Perry explained: “This largely reflects the fact that white evangelicals are VERY Republican & VERY conservative. When we look at answers to these questions across partisanship and ideology, clearly the more Republican and the more conservative, the more you prioritize conquering over cooperating.”

“White Christian nationalism is almost pure ‘us vs. them’ ideology,” Perry tweeted. “The more white Americans subscribe to Christian nationalism ideology, the more they prioritize overcoming opponents rather than overcoming differences to solve problems. No unity with rivals. In fact, it’s darker than that. The more whites affirm Christian nationalism, the more they say (the) USA would be better off if the Dems ceased to exist. And note, you don’t get as strong opposition to the GOP as whites reject Christian nationalism. Pattern is asymmetrical. Affirming Christian nationalism = quashing rivals; Rejecting Christian nationalism not as much. What this means is that white Christian nationalism IS NOT a unifying ideology broadly speaking, but rather Christian nationalism only promotes unity to war against political enemies. In other words, Christian nationalism is not a pathway forward for an increasingly diverse US. It’s an ideology bent on conquering ‘others.’”

“Christian nationalism is not a pathway forward for an increasingly diverse US. It’s an ideology bent on conquering ‘others.’”

Anthea Butler, 2022 recipient of the Martin E. Marty Award for the Public Understanding of Religion, added, “I’d say it more strongly: it’s a formula for radicalization.”

A license to proselytize vs. a mandate to love

If “everyone except white evangelicals” believes in cooperation rather than conquering, then it seems reasonable to ask what is unique about white evangelicals that might lead them to prefer conquering to cooperating.

Perry went on CNN’s Newsroom with Alisyn Camerota and Victor Blackwell last Tuesday afternoon and said we need to confront white Christian nationalism by getting back to our democratic values and reminding them there is nothing conservative about what they are doing.

But while emphasizing our democratic values is important, we cannot miss the theological seed and soil from which the white Christian nationalism grows:

- White evangelicals believe in a God who seeks self-glory that overflows in infinite wrath by punishing every moment of every life, dishonors everyone through cursing, and who ultimately will receive glory by evangelicals rejecting love of their neighbors.

- White evangelicals believe in a kingdom where God conquers the cosmos and subjects everything and everyone in it to submission under the threat of eternal torture while commissioning those who submit to rule and reign over everything.

- White evangelicals believe in a gospel that promotes small-minded, abusive views of authority, other religions, sin and justice, human identity, suffering and the cosmos.

- White evangelicals believe in a church where the pastor wields power over the congregation, men wield power over women, parents wield power over their children, and everyone wields power over their image for the sake of their mission of making disciples.

And white evangelicals believe in a Great Commission that uses missions to export its male-dominated glory hierarchies and Christian nationalist politics.

Even if most white evangelicals do not explicitly embrace the dominion theology that attempts to place Christians in charge of the nation while establishing their view of biblical laws, their basic theology sets up a conspiratorial alternate reality that is too easily harnessed by those who do.

While discussing the “almost desperate tone” of conservative centrists David French and Ed Stetzer’s commentary regarding their conspiratorial, post-truth fellow conservatives, scholar Chrissy Stroop wrote, “Neither man is willing to dig down to the roots of the problem — namely, the conservative evangelical theology that, as scholars in religious studies and sociology have demonstrated, was developed within, and with the purpose of justifying, an unjust hierarchical social order.” She went on to conclude, “White evangelical subculture is a perfect recipe for authoritarianism.”

“White evangelical subculture is a perfect recipe for authoritarianism.”

This authoritarianism is ultimately an insecure attempt to control others so that white evangelicals can save their kids from being set on fire by their God for eternity. Authoritarian politics is the fruit of hierarchical theology. The language conservative evangelicals use is “living out the gospel.” They have their formal doctrine of the gospel as hierarchical power, which is shaped in part by culture in ways they are unaware of, that they live out in their politics and ethics.

But what do any of these power-grabbing glory hierarchies have to do with love? And rather than seeing Christians as foundationally called to victory or success as those on the right believe, or even to unity in faithfulness as the centrists believe, what if Christians saw themselves as foundationally called to love?

In an interview during my fellowship with Baptist News Global, circuit court judge and pastor Wendell Griffen told me: “Bad theology always produces demented psychology. Demented psychology produces dysfunctional sociology. Dysfunctional sociology always produces oppressive anthropology, and then they always produce oppressive economics and ideologies. So it all flows from bad theology. If your notion of God is wrong or flawed, your notion of self, and others, and power is wrong. … If your theology is wrong, you read the Great Commission as a license to go proselytize, as opposed to a mandate to do love and justice, and to model love and justice, and to call on the society and the world to be instruments of love and justice.”

Ideological cohesion vs. radicalization

Part of the struggle all of us have is the desire to advance our values without getting caught up in the pull toward extremism.

According to Pew Research, Democrats and Republicans both have become more “ideologically cohesive.” Pew calculated the number of moderates in Congress has gone from more than 160 in 1971-72 down to just two dozen today.

But while Democrats have become more liberal to a smaller degree, Republicans have become “much more conservative.” And while the U.S. population is 65% Christian, the 117th Congress is 88% Christian. Pew Research measured the net result of the Republicans’ more extreme move to the right has been that “on average, Congress has become more conservative over the past five decades.”

In an article titled “Confronting Asymmetric Polarization,” political scientists Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson agree, stating: “There is mounting evidence that the increasing distance between the two parties is primarily a consequence of the Republican Party’s 35-year march to the right.”

Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson (courtesy of BillMoyers.com)

Hacker and Pierson point to the moderate record of Democratic-appointed Supreme Court justices in comparison to four current GOP-appointed justices being “among the most conservative justices to serve on the court in the last 75 years,” with Justice Anthony Kennedy finishing in the top 10. They point to the way Republicans have utilized the rise of the Tea Party, the filibuster, government shutdowns, voter disenfranchisement and the “hostage-taking” of debt ceiling increases, among other examples of this growing radicalization.

The result has been a net negative for the Democrats. They explain, “Unless dysfunction is clearly attributable to a particular set of politicians affiliated with the GOP, it generally hurts the party associated with an active use for government (that is, Democrats).”

Political purity vs. political survival

Those who position themselves as centrists or moderates face the challenge of wanting to confront the extremism in their group, while also trying to survive.

Hacker and Pierson point out that “most GOP extremists will not pay an electoral price at all for moving in that direction — on the contrary, they pay a price for moderation.” Thus, for Republicans, “It is far more costly to be moderate (and face a well-funded primary challenge) than to stay at or move toward the extreme.”

Unfortunately, religious and politically centrist Christians have proved not to be up to the challenge of confronting the extremism from those on the right. Stroop says the reasons these more “respectable” evangelicals have been unsuccessful are that “they have failed to convince their coreligionists that supporting Trump is hypocritical or damaging; they have failed to take responsibility for the harm they have done by encouraging the culture wars and trying to put a benevolent face on them; they have failed to maintain control of the national conversation around evangelicalism to the extent they once did, which contributed to the major U.S. media’s tendency to normalize extremism.”

Empowering true centrists vs. enabling radicalization

For those of us who tend to be more to the center left or even farther left, the challenge becomes how to root out the extremism on the right. To do that, our relationship with conservative centrists can become complicated.

Historian Kristin Du Mez said in a recent piece on Christian nationalism that we need to consider how theological beliefs may be “situated in the context of other interests — things like racial privilege, class identity and gendered relations of power.”

I would add that we need to examine how theological beliefs may foster and shape certain views of race, class and gender. As we’ve seen in Voddie Baucham’s justification of violence against women and children, John MacArthur’s defense of slavery, or the pro-life movement’s pursuit of eugenics, white evangelical theologies of power have fueled power dynamics and abuse.

The moment we’re in is not a both sides problem.

The moment we’re in is not a both sides problem. It is a unique phenomenon of the religious and political right. They are the ones who want to conquer rather than cooperate. Conservative and progressive centrists need to stop playing the “both sides” card and start focusing on where the problem lies.

Joyce wrote, “Seeing the right for what it is and has been — a reactionary, hierarchical movement — sits at the core of where truthful political analysis and faithful action begins.”

Because ex-evangelicals like myself want to root out these power dynamics at their theological seed and soil level, we tend to pair religious and political centrists into the same group as the extremists. After all, if they hold to the same core theologies of power and exclusion, what is the difference if they simply smile, wear jeans or talk more calmly while they discriminate against others?

Stroop made a similar point: “While elite evangelicals like Peter Wehner, Michael Gerson, and David French all find Donald Trump a bridge too far, they have long supported the kind of Christian schooling that serves to indoctrinate children in patriarchal and anti-LGBTQ views, toxic purity culture, Christian nationalist history, young earth creationism, and right-wing political ideology.”

So for Stroop, conversations about Christian nationalism must start including more secularists and ex-evangelicals “who know white evangelical subculture intimately” because they “have been sounding alarm bells for years. … The lesson of the Trump years could and should be that if the media learns, with the help of ex-evangelicals, to cover the danger of Christian nationalism accurately, it could make possible a healthier democratic future in the United States of America.”

But for Hacker and Pierson, the path forward is to “reestablish norms of moderation, reduce the incentives for obstruction, (and) strengthen the forces of moderation within the GOP.”

Whether we normalize moderation at the risk of enabling radicalization, or confront the entire system at its theological roots, wisdom for the path forward may not be so binary. Perhaps there will be a spectrum of strategies that will be necessary for different moments and challenges.

The last word

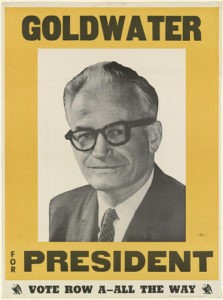

While most religious and political arguments tend to drone on due to people vying to have the last word, I’ll close by giving the last word to a conservative.

Republican senator and presidential nominee Barry Goldwater said back in 1994: “Mark my word, if and when these preachers get control of the (Republican) party, and they’re sure trying to do so, it’s going to be a terrible damn problem. Frankly, these people frighten me. Politics and governing demand compromise. But these Christians believe they are acting in the name of God, so they can’t and won’t compromise. I know, I’ve tried to deal with them … .

“These Christians believe they are acting in the name of God, so they can’t and won’t compromise.”

“There is no position on which people are so immovable as their religious beliefs. There is no more powerful ally one can claim in a debate than Jesus Christ, or God, or Allah, or whatever one calls this supreme being. But like any powerful weapon, the use of God’s name on one’s behalf should be used sparingly.

Barry Goldwater campaign poster, Smithsonian Museum.

“The religious factions that are growing throughout our land are not using their religious clout with wisdom. They are trying to force government leaders into following their position 100%. If you disagree with these religious groups on a particular moral issue, they complain, they threaten you with a loss of money or votes or both.

“I’m frankly sick and tired of the political preachers across this country telling me as a citizen that if I want to be a moral person, I must believe in ‘A,’ ‘B,’ ‘C,’ and ‘D.’ Just who do they think they are? And from where do they presume to claim the right to dictate their moral beliefs to me?

“And I am even more angry as a legislator who must endure the threats of every religious group who thinks it has some God-granted right to control my vote on every roll call in the Senate. I am warning them today: I will fight them every step of the way if they try to dictate their moral convictions to all Americans in the name of ‘conservatism.'”

Rick Pidcock

Rick Pidcock is a 2004 graduate of Bob Jones University, with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Bible. He’s a freelance writer based in South Carolina and a former Clemons Fellow with BNG. He recently completed a Master of Arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five children and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder. Follow his blog at www.rickpidcock.com.

Related articles:

White evangelicals want to control you so their kids can live forever | Analysis by Rick Pidcock

The deconstruction of American evangelicalism

Attacks on Critical Race Theory didn’t come out of nowhere, panelists say