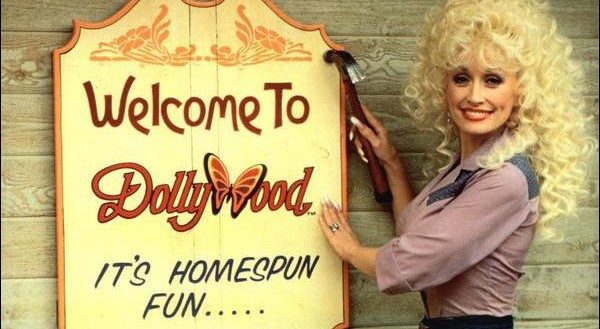

I went to Dollywood for the first time this summer, a pilgrimage of sorts. After all, Dolly Parton is a larger-than-life icon, and Dollywood is so much more than just an amusement park.

Dolly grew up in poverty in Sevierville, Tenn., and now she’s worth half a billion dollars. She hasn’t forgotten East Tennessee, though. In fact, she’s invested deeply in the region and has had a significant economic impact on the people of her home county.

In 1990, about a third of high school students in Sevier County dropped out, a decision they had made as early as fifth or sixth grade. So that year, Dolly invited Sevier County’s fifth and sixth graders to Dollywood. She had them pick a buddy, and she told them if they both graduated, she’d give them each $500. The dropout rate in Sevier County plunged to 6%, where it has stayed.

Susan Shaw

In 1995, Dolly started the Imagination Library to encourage childhood literacy in Sevier County. She provided a free monthly book mailed to the home of every family with a child 5 years old and younger. The program was so successful it expanded around the world. By 2018, the Imagination Library had given away 100 million books.

Dollywood has helped create 23,000 jobs in East Tennessee and has an annual direct and indirect impact of $1.8 billion on the local economy.

When wildfires devastated Gatlinburg in 2016, Dolly’s foundation provided $1,000 per month for six months to about 900 affected families. The Dollywood Foundation also set up a fund to help families and clean up homesites. All told, the Foundation gave $12.5 million to people impacted by the fire.

Still, when Tennessee legislators wanted to put a statue of her at the state Capitol, Dolly turned them down. “Given all that’s going on in the world, I don’t think putting me on a pedestal is appropriate at this time,” she said.

She also turned down the Presidential Medal of Freedom under Donald Trump — twice, once because of her husband’s illness and the second time because of COVID.

Asked if she’d accept it now, she said maybe not. “Now I feel like if I take it, I’ll be doing politics, so I’m not sure. I don’t work for those awards. It’d be nice but I’m not sure that I even deserve it. But it’s a nice compliment for people to think that I might deserve it.”

That’s the thing about Dolly. Somehow, she’s managed to draw everyone in. She’s beloved in the gay community and in Tennessee’s Republican Legislature.

“That’s the thing about Dolly. Somehow, she’s managed to draw everyone in.”

Walking around Dollywood, you see the whole broken, beautiful world there, baptized together at Daredevil Falls, sharing the communion of freshly baked cinnamon bread and coffee, and singing the hymns of Dolly’s repertoire that play all over the park. Dolly intends her theme park as a place of welcome for everyone. In relation to her LGBTQ fans who visit, Dolly said Dollywood is “a place for entertainment, a place for all families, period. It’s for all that. But as far as the Christians, if people want to pass judgment, they’re already sinning. The sin of judging is just as bad as any other sin they might say somebody else is committing. I try to love everybody.”

For a few hours up in the Smoky Mountains, Dolly lets us see another possibility, a world where we can all tap our toes together, smile at one another, and share a bench in the shade.

I’ve always thought it quite daunting to approach moral and ethical dilemmas by asking, “What would Jesus do?” After all, living up to Jesus is quite a lot to aspire to do. Dolly, on the other hand, despite all her fabulousness, is a mere mortal and a much more achievable role model. Dolly admits as much in one of her songs: “I am a seeker, a poor sinful creature, there is no weaker than I am.”

So, when faced with the big questions, perhaps we should ask, “What would Dolly do?” After all, as Dolly tells it, she took what she had and made something of it. She did what she could within her sphere of influence.

“Dolly, on the other hand, despite all her fabulousness, is a mere mortal and a much more achievable role model.”

Granted, most of us don’t have half a billion dollars and worldwide fame to work with. But we have what we have. Wasn’t that, after all, the point of the story about the widow’s mite? She did what she could with what she had.

When Dolly became aware of the problems with the word “Dixie,” she changed the name of one of her attractions. “When they said ‘Dixie’ was an offensive word, I thought, ‘Well, I don’t want to offend anybody,’” she said. “’This is a business. We’ll just call it The Stampede.’ As soon as you realize that (something) is a problem, you should fix it. Don’t be a dumbass. That’s where my heart is. I would never dream of hurting anybody on purpose.”

She also voiced her support for Black Lives Matter. “I understand people having to make themselves known and felt and seen,” she said. “And, of course, Black lives matter. Do we think our little white asses are the only ones that matter? No!”

We can all make change where we are. We can show up and speak up for the marginalized and oppressed. We can be kind. We can do the right thing even when it’s hard and it might cost us. We can be like Dolly, who in her own very human and very special way is a lot like Jesus.

Susan M. Shaw is professor of women, gender and sexuality studies at Oregon State University in Corvallis, Ore. She also is an ordained Baptist minister and holds master’s and doctoral degrees from Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. Her most recent book is Intersectional Theology: An Introductory Guide, co-authored with Grace Ji-Sun Kim.