Justified condemnations of Alabama’s plan to execute a convicted killer Jan. 25 using an untested gas serve as a distraction from the ultimate need to end the death penalty altogether, Katie Owens-Murphy said during a webinar hosted by Equal Justice USA.

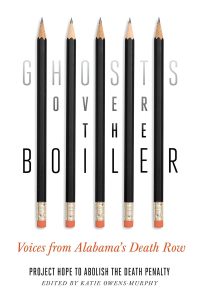

“I really appreciate the op-eds I’ve seen come out over the last few weeks where folks have really taken an opinionated stance. But when we focus too much on the methods (of execution), we lose the forest from the trees and don’t focus on abolition as a whole, which ought to be the goal,” said Owens-Murphy, editor of Ghosts Over the Boiler: Voices from Alabama’s Death Row.

Kenny Smith

Causing the uproar is the state’s plan to use nitrogen hypoxia to kill Kenny Smith Jan. 25. The gas never has been tested for executions but has caused serious injuries and death in industrial accidents.

Smith’s attorneys say the method is experimental and cruel, and the United Nations announced the procedure will violate international laws against torture. Nevertheless, the Alabama Supreme Court and a federal judge rejected appeals to stop the execution.

“The execution scheduled for next week is garnering international media attention,” she said. “I think the reporting, while important, misses the opportunity to ask why it is that we execute people.”

“The reporting, while important, misses the opportunity to ask why it is that we execute people.”

Owens-Murphy, an associate professor of English at the University of North Alabama, spoke during the Jan. 17 “In the Movement” webinar hosted by EJUSA’s Evangelical Network.

Besides her discussion of impediments faced by the abolition movement, Owens-Murphy’s hour-long presentation included a discussion of Ghosts Over the Boiler, a collection of essays, poetry, photography and art created by Alabama Death Row inmates who also run their own nonprofit organization.

“Project Hope to Abolish the Death Penalty is the only 501(c)3 nonprofit founded and run by people on Death Row in the nation,” Owens-Murphy said.

Katie Owens-Murphy

While its executive director, Esther Brown, and advisory board members are not in prison, the group’s entire board of directors is made up of condemned inmates, she said. “Folks on the outside help with various projects, but it’s all inside-lead. They do advocacy. They do special projects. They do archival work. And they do it all from Death Row.”

One of their key tasks includes publishing Wings of Hope, a quarterly newsletter that wages moratorium campaigns and includes prose and poetry, opinion pieces and visual art. The project is arranged by the prisoners and then digitized and posted online by Brown, Owens-Murphy said.

“That’s the way they inform each other about policy changes. One of their mantras is, ‘You’re only as good as your lawyer.’ The idea is that they have to stay up to date on their own cases and on Alabama policy — which has been changing quite frequently on the death penalty — in order to be the best advocates for themselves.

That advocacy is “amazing” given the nonprofit has been operating continuously since 1989 despite the terrible realities of Death Row in Alabama, she said.

“They are all dying, being resentenced — they’re all leaving in one way or another but the organization itself somehow remains intact and remains this incredible vehicle for abolitionist change. So, obviously they’re amazing.”

The inmates extended the reach of their advocacy work when they agreed to Owens-Murphy’s pitch for a book of the group’s recent and more distant work.

“We spent years putting together proposals, selecting pieces, and at the same time Esther started sending me some of their earlier newsletters that had not been archived online,” she explained.

The project also helped launch the University of North Alabama’s Alabama Death Row Archives, a collection of manuscripts, photographs, audio files and other documentation about the history and practice of the state’s capital punishment system.

The project also helped launch the University of North Alabama’s Alabama Death Row Archives, a collection of manuscripts, photographs, audio files and other documentation about the history and practice of the state’s capital punishment system.

The persistence of the Death Row inmates demonstrates an inspiring level of grit and determination.

“The motivation to keep going after watching and witnessing so many of their friends ‘go around the corner,’ as they put it, to be executed,” Owens-Murphy noted. “And the fact that they’re still motivated to continue the work, continue the organization and continue the legacy of the founding members, is the one of the most poignant examples of resiliency I’ve ever witnessed.”

But Owen-Murphy said she continues to lament how the narratives around the implementation of the death penalty create distractions for the wider abolition movement.

The attention generated when executions are botched, or when the issue of innocence is debated, are further examples of that phenomenon.

“Sometimes the conversation takes a left turn when we talk about botched or failed executions, as if there could be a proper execution,” she said. “And sometimes I get a little frustrated with conversations about innocence, as if we could just get it right and then executions would be sound.”

Smith’s case is generating the intense media attention because of the execution method and because the first attempt to execute him, by lethal injection, was botched in 2022.

“He spent hours being poked and prodded with needles before the death warrant expired at midnight,” Owens-Murphy said.

And there is no guarantee the experimental use of nitrogen gas will be any less painful for Smith, she explained. “It’s going to be the first. It’s untested. The veterinary society does not use it to euthanize animals. The U.N. just came out with a statement condemning its use and warning that it will be in violation of international treaties.”