I grew up in a fundamentalist Southern Baptist church in Georgia. I was on the “cradle roll” from the time I was six weeks old, and I was at church “every time the doors were open,” as the saying goes.

What I learned in that church was a perfect setup for sexual abuse for a child who took it all in and believed it all wholeheartedly. I so deeply internalized the church’s messages that no one had to tell me to keep quiet or take responsibility for my own abuse. Oh no. I did it all for myself. I believed every word the church told me, and so I was set up — to be abused, to keep quiet about it, and to blame myself for what happened to me.

God is in control

The God of my Southern Baptist church was in control of everything. Whatever happened was God’s will. Sure, humans had some choice and could go against God’s desires, but whatever wasn’t in the “perfect will of God” was in the “permissible will of God.” So, while abuse was not within God’s “perfect will,” it was in God’s “permissible will.”

Susan Shaw

That meant even if God didn’t cause or will abuse, God allowed it. In other words, God could have stopped it — because God controlled everything — but God consciously chose not to stop it.

My abuse was God’s will in one way or another. Who was I to question it?

You are to submit to those in authority over you

This God of my childhood was terrifying. He (and it was always “He”) loved me, but he also could destroy me at any given moment. Like Lot’s wife, I could be reduced to a pile of salt if I didn’t obey.

This God who loved me had provided me one way to salvation, but if I chose to forgo that path, he would condemn me to eternal damnation in the flames of hell. He could punish me with untold earthly sufferings to teach me lessons I needed to learn. So I’d better love him and obey him or else.

“God’s pattern was that of an abuser: I love you, and I have the power to destroy you.”

God’s pattern was that of an abuser: I love you, and I have the power to destroy you. So, you better do what I tell you to do, or I’ll use my power to crush you. It’s all for your own good, so you should love me and thank me for it.

Utter submission to God was an absolute requirement.

Our metaphors for God reinforced our subjugation: Father, Lord, King, Master. So did our hymns: “Trust and obey,” “I surrender all,” “Have thine own way, Lord,” “Perfect submission, perfect delight.” We also heard the Bible verses: “Behold, I set before you this day a blessing and a curse. A blessing if you obey the commandments of the Lord your God, which I command you this day. And a curse, if you will not obey the commandments of the Lord your God;” “Wives, submit yourselves to your husbands, as unto the Lord;” “Obey them that have the rule over you, and submit yourselves.”

Our images of God were male, and my church was clear that we were to submit and obey in the same way to the men who stood in God’s place for us — pastors, husbands, fathers and leaders.

“I was an 11-year-old girl who trusted and obeyed. I was completely set up by my church’s theology to accept what happened to me as God’s will.”

No wonder my child-self did not feel in any position to resist what was happening to her. Having been told my whole life to submit — to God and the men in God’s stead — what else was I going to do? I was an 11-year-old girl who trusted and obeyed. I was completely set up by my church’s theology to accept what happened to me as God’s will.

If it’s a sexual sin, it’s your fault

Despite accepting my abuse as the “permissible will of God,” I was acutely aware that anything sexual outside of marriage was sin. So, I believed I was sinning. After all, it had been drilled into my head that whatever I did was a choice I made to obey or disobey God.

So, by participating in my abuse, I was choosing to engage in sexual sin. My prayer, then, was not for God to make my abuse stop; my prayer was for God to give me the strength to make it stop. Every time I “allowed” myself to be abused, I prayed for God’s forgiveness because I did not stop the abuse.

I also lived in a culture that did not talk about sex at all. The only thing my church said about it was not to engage in it. I doubt that at 11 I even had the words to talk about what was happening to me. I was too mortified by my shame to say anything to anybody. And it was the 1970s. Who would have believed me anyway?

Certainly not the church that prioritized men and boys over girls and women. Not the church that told us how women were sexual temptresses who needed to safeguard vulnerable men from their sexual wiles. All we have to do is look at the disastrous response of the Southern Baptist Convention to its sex abuse crisis to know I was right.

You need to forgive your abuser

My church also set me up by teaching me that forgiveness for any sin against us was a requirement. I wasn’t supposed to be angry about what was happening to me. I was supposed to forgive and forget.

I certainly wasn’t supposed to throw my abuser under the bus and bring potentially horrible consequences down on his head — and likely mine (if I was even believed). My role was to forgive and, if I didn’t forgive, then I was sinning and would have to face God’s consequences.

How much more silencing a message could I have received? I didn’t have to speak aloud what was happening to me because I needed to forgive and wash the slate clean — every time, and no matter how many times, something happened.

You have to deny yourself

My church also told me my self wasn’t important. Self-denial was the way of the Cross, the way of Jesus. If we were called to be Abraham’s sacrifice on the altar, so be it. Putting everyone else ahead of yourself was God’s way for us.

That meant I had to consider my abuser and put him first. To put myself first, to speak against what was happening to me, would have been selfish because it could have brought harm to my abuser and his family.

“To put myself first, to speak against what was happening to me, would have been selfish because it could have brought harm to my abuser and his family.”

I was constantly reassured by the church that all things worked together for good. So no matter what was happening to me, God was using it — perhaps causing it, definitely allowing it — for some good God wanted to come of it.

My abuse was supposed to teach me something. God would make something good of it for me. I just had to be the good, submissive girl, and God would take care of things down the road.

Surviving God

Only in my early 20s did I finally tell someone what had happened to me. I was in seminary and so found a place to begin to ask the hard questions my childhood theology denied me.

Only in my early 20s did I finally tell someone what had happened to me. I was in seminary and so found a place to begin to ask the hard questions my childhood theology denied me.

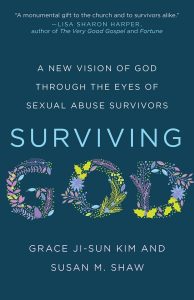

Now it’s taken me into my sixth decade to write about my abuse and my theological journey. Grace Ji-Sun Kim and I have just published Surviving God: A New Vision of God through the Eyes of Sexual Abuse Survivors with Broadleaf Books.

The church has to do better. What I experienced isn’t uncommon. Grace writes about her experiences, too, in the book, and we draw from the words of other survivors to ask what happens when we begin doing theology from the perspectives of survivors.

These traditional theologies of God’s omnipotence and omniscience, God’s maleness and dominance, God’s system of punishment and reward have to go. They enable abuse. They serve patriarchy and other forms of oppression, and they continue to set up children, women, LGBTQ people, people with disabilities and vulnerable men for abuse, silencing and ongoing trauma.

Susan M. Shaw is professor of women, gender and sexuality studies at Oregon State University in Corvallis, Ore. She also is an ordained Baptist minister and holds master’s and doctoral degrees from Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. Her most recent book is Surviving God: A New Vision of God through the Eyes of Sexual Abuse Survivors, co-authored with Grace Ji-Sun Kim.

Related articles:

Decent men of faith and sexual abuse | Opinion by Martha Dixon Kearse

Why can’t churches get handling abuse right? | Opinion by Susan Shaw

Our ‘sin of the bystander’ enables sexual abuse. We must change | Opinion by Kathy Manis Findley