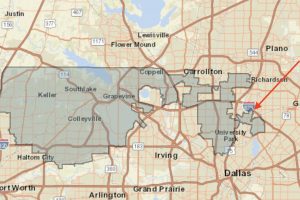

True natives of Phillips County, Arkansas will attest that the “Arkansas Delta” isn’t a delta at all. It’s an alluvial plain. Over the last 12,000 years, the imposing Mississippi River and its tributaries deposited deep layers of soil, gravel, and clay carried from slopes as far away as the Rocky Mountains to the west and the Appalachians to the east. Today, the rich loam of the Mississippi Alluvial Plain — some of the world’s most productive farmland — is also extremely dense, flat and poorly drained. Hazard mingles with fertility, as the threat of flooding looms. And like the muddy shores of the Mississippi, the Delta’s storied African American communities have always confronted both the abundance and the peril of life in the Delta, hoping to God that the levee holds.

Willard B. Gatewood, Distinguished Professor of History at the University of Arkansas, called the Arkansas Delta the “deepest of the Deep South,” for, in its fertile soil, cotton thrived and with it, slavery. Black slaves comprised the majority of the Delta’s population throughout the mid-nineteenth century. Following the Civil War, freepeople established their own communities and culture along the river, though white landowners proved reluctant to surrender the bigoted power they had exercised for so long. Thus, sharecropping and tenant farming became a way of life for most, but by the second half of the 20th century, mechanization had all but replaced human farming labor in Phillips County. When the Mohawk Rubber Company closed in 1978, vast unemployment set in for the long haul.

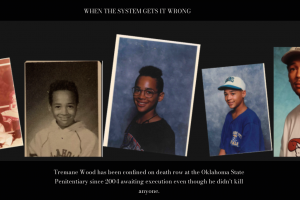

Helena and other communities along the Mississippi River confront the beauty and the danger of existing in a flood plain.

Today, Phillips County’s mostly black families now contend with a complex and all-too-familiar relationship with the Arkansas Delta — a place where sharecroppers lived in segregation yet built a bastion of black culture. In the county seat of Helena-West Helena, black and African American families comprise 76 percent of the population and shoulder 96 percent of its poverty. Furthermore, Helena’s median household income of $21,000, remains less than 40 percent of the national median, leaving its high population of children and teenagers to contend with little access to health care, steady meals, extracurricular activities, and education resources.

Still, you will not find a more loving, tight-knit and dedicated community than Helena’s, says Janee’ Jones Tisby, director of Together for Hope Arkansas, part of the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship’s rural development coalition. For nearly 20 years, Together for Hope (TFH) has cultivated an unshakable relationship with the Helena community and partner churches across the country as they engage in asset-based development among children and teenagers. With a precise focus on literacy and leadership development, TFH continues to build children’s imaginations for what is possible beyond the limited view of poverty. Every June, that work culminates in the wildly-popular Swim Camp, where children and teenagers not only learn to swim but learn to pursue leadership through lifeguarding, volunteering and interning with TFH.

Children take center stage, Tisby says, but the kinship that has formed between Helena’s black community and mostly white “outsiders” who come to volunteer is equally staggering. In fact, most partner churches and volunteers consider their annual visit to Helena the highlight of their year, says Kate Hall, member of Hayes Barton Baptist Church in North Carolina and the original architect of Swim Camp. Rather than see only poverty and lack, she says, the wider Together for Hope community has come to know Helena as a place of beauty and strength, full of old friends.

Even so, like the blues songs born in the Delta’s muddy waters, it’s easy to get lost in the sultry tune of kinship and forget the lyrics that bear witness to black oppression: “Backwater rising, Southern peoples can’t make no time / I said, backwater rising, Southern peoples can’t make no time / And I can’t get no hearing from that Memphis girl of mine,” sings Blind Lemon Jefferson, one of the fathers of blues music.

Like the rising river, the persistence of poverty still looms just over the levee, threatening to wash young people down paths of violence, drugs, food insecurity, unemployment, and early death. That’s why Together for Hope is committed to growing the gifts and dreams of Helena’s children as they seek to interrupt cycles of generational poverty and instill lasting hope in the Delta’s youngest.

Read more in the Arkansas Delta series:

At the center of Helena, Arkansas’s fight against poverty and division: an 85-year-old swimming pool

Imagination is the greatest threat to Delta poverty, Together for Hope Arkansas says

Phillips County, Arkansas: Backwater Rising

Video: Janee’ Tisby on Volunteers

Video: Janee’ Tisby on Poverty

Video: Earnest Womack on the Pool

Video: Earnest Womack on Poverty

Related commentary at baptistnews.com:

Survival mode | Jason Coker

Reimagining churches as full-time partners with those in poverty | Laura Rector

Related news at baptistnews.com:

Hope blooms in the Arkansas Delta, thanks to ministry team

Like the rising river of the Arkansas Delta, the persistence of poverty still looms just over the levee, threatening to wash young people down paths of violence, drugs, food insecurity, unemployment, and early death. That’s why Together for Hope is committed to growing the gifts and dreams of Helena’s children as they seek to interrupt cycles of generational poverty and instill lasting hope in the Delta’s youngest.

This series in the “Resilient Rural America” project is part of the BNG Storytelling Projects Initiative. Has the United States forgotten its countryside? What strength and resilience may yet be stirring outside our city limits? In “Resilient Rural America,” we attempt to answer these questions when we visit these unique communities to examine the singular nature of poverty in rural America and tell the stories of development among its courageous and resilient people.

_____________

Seed money to launch our Storytelling Projects initiative and our initial series of projects has been provided through generous grants from the Christ Is Our Salvation Foundation and the Eula Mae and John Baugh Foundation. For information about underwriting opportunities for Storytelling Projects, contact David Wilkinson, BNG’s executive director and publisher, at [email protected] or 336.865.2688.