I was reading church minutes, bored out of my mind. Not the first time, nor probably the last. Then, I wondered: Why? Why was I so disconnected from what these markers of congregational history have to say?

Perhaps some of it stems from being formed in the Missionary Baptist churches of Texas. I grew up as a poor Black boy, among an excess of riches with regard to homiletical geniuses.

Our preachers wielded a Baptist faith that roused our socially beleaguered congregants with the words Christ and his followers supplied to beat back oppression, empire and daily life. They called it “equipping the saints.” They weren’t afraid to call out demonic forces like racism, poverty and inequality that threatened and limited our lives.

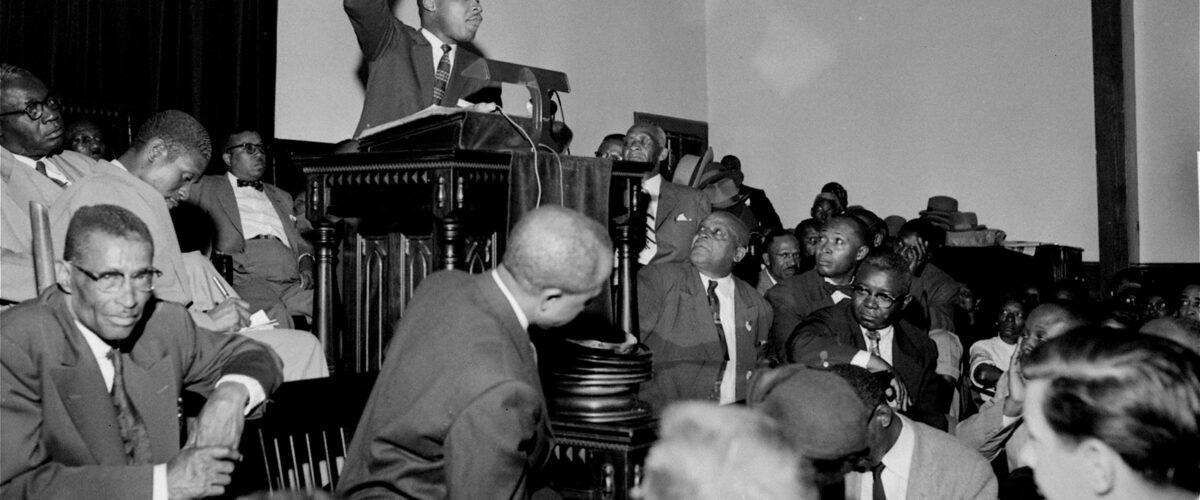

George Oliver

When my father and grandfather died, Shiloh Missionary Baptist Church in Edna, Texas, made it a point for the pastor to take me out to dinners, for deacons to take me fishing and for women in the church to help relieve my disabled grandmother from always having to cook for us. They never debated their role in people’s lives.

We even had to take minutes in Sunday school. Reporting was a moment of public pride for continuing the work of our ancestors.

And they were proud to record it all. We even had to take minutes in Sunday school. Reporting was a moment of public pride for continuing the work of our ancestors.

When I attended Andover Newton Seminary in New England, we often heard about a group of pre-Civil War alums who were so committed to justice, they rode directly from graduation in Newton, Mass., to Kansas. They established churches dedicated to abolition and specifically a slave-free Kansas entering the Union.

In this same period, First Baptist Church in Jamaica Plain, Mass., — at the time home to the Converse family of shoe fame and the Welds of political pedigree — like many other Northern Baptist churches, recorded serious statements on abolition in their annual reports, making passionate pleas for taking any means available to set captives free. They actually used business meetings to discuss national war and peace, as well as the church’s roles in liberation, as the official business of the church.

The church should be directly engaged in whatever impairs the lives of the faithful, and God’s house is not just a place for worship, but the center of community transformation.

I was raised in and educated by two vastly different communities and value sets, but their histories share two common values: The church should be directly engaged in whatever impairs the lives of the faithful, and God’s house is not just a place for worship, but the center of community transformation.

The lives of God’s people are being threatened in part by faith orders, and we — as a Baptist, I emphasize us — have lost the capacity to be the thought centers of our communities.

Many of our churches chose strategic segmentation. They picked winners and losers in pulpits, pews and politics. They highlighted sin and poorly defined grace. And compassion, meaning to be “with suffering,” was all too often maligned as a sign of weakness. Many mainline Christian Progressives have the right impulses but impractical methods for connecting with the diverse populations required to make change.

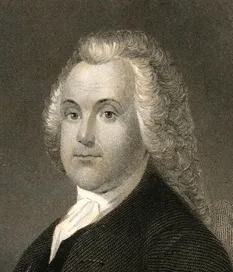

Roger Williams

Long ago, Baptists founded American notions of pluralism in Rhode Island. In this colony-then-state where Baptists dominated, we adopted a “shared-community” model of governance religiously. The Congregationalists, Catholics and Pennsylvania Dutch chose monolithic religious hierarchy as their states’ established faith structure. If that sounds strange, prior to the 14th Amendment, the First Amendment only explicitly prevented the federal government, not states, from establishing a religion. So, many of them did. Massachusetts became the last state to disestablish religion in 1833.

The U.S. Supreme Court seems to be aligning its mission with the loudest fringe elements of the Cultural Conservative movement. Roe v. Wade’s reversal and subsequent undermining of privacy protections comprises a threat to a whole lot of people — and a whole lot of what makes life American.

This is not a call to join the Democratic Party, but it is a cry for Baptists to look at ourselves anew.

Our forebears did not totally misappropriate our faith. At times, they even inflected it for the nation to be made better. They abolished slavery in their minutes. Do we abolish racism or poverty in ours? They established modern ways of religious cooperation in state governmental systems, which eventually took hold federally. As former American Baptist General Secretary Lee Spitzer reflected, Baptists even defied Nazism in Germany prior to World War II. What are our minutes recording now?

We read about Methodist schism, Southern Baptist scandal and generic religious decline. But how irrelevant are we making our churches in what we reflect on as our business?

We read about Methodist schism, Southern Baptist scandal and generic religious decline. But how irrelevant are we making our churches in what we reflect on as our business?

When rights are being reduced in courthouses and statehouses, Baptists can’t keep shrinking from finding a coherent message to unite us. When children and churchgoers are being slaughtered by weapons of war in the hands of teenagers, Baptists can’t keep hiding behind, “We’ve got people on both sides here.” If “our business” isn’t successfully having those conversations in our walls, how will we ever graduate to these successful conversations in our families and communities.

Jesus the Teacher needs a teaching church again. Jesus the Evangelist needs a preaching church again, which is not constrained by walls or labels. Jesus needs us out sharing his understanding with people again. But Jesus shared with priests and paupers, philosophers and prostitutes, Peters and Pilates. Jesus blessed Jews and Gentiles, worshipped in the Temple with Jews, and in the hills taught Samaritans.

We can’t be that kind of church today if we don’t know our neighbors and if they don’t know we can capably stand up for their lives and livelihoods.

Church can’t primarily be for singing, cat fights and shaming. We have to measure ministry based upon the needs of our communities and the calls of our day.

Church can’t primarily be for singing, cat fights and shaming. We have to measure ministry based upon the needs of our communities and the calls of our day. Our minutes should reflect what’s really happening today and how Jesus summoned us in this day to respond to it.

Future generations need to hear how we overcame pandemic, political insurrection, inflation, war in Ukraine and polarization. This is the business of the church and vital to lives under our charge.

Baptist churches should connect with neighbor and nation — and write down how it goes. The future deserves a better account than the one we’re providing.

Our Baptist story must get back to being ahead of time, instead of barely chasing it.

George Oliver is pastor of Grace Baptist Church in San Jose, Calif. He’s a Texas native who earned degrees from Sam Houston State University and Andover Newton Seminary and is ordained to ministry in the American Baptist Churches-USA and Alliance of Baptists.